Comp Care, CPC: Opposite Case Histories in O.C. : Hospitals: Both companies operate mental health facilities. One is solidly successful; the other is floundering.

James Conte checked himself into a Salt Lake City psychiatric hospital Monday night. The 61-year-old company chairman wasn’t suffering from depression, exhibiting schizophrenic tendencies or struggling with an eating disorder.

He simply wanted to make sure that the sheets were clean, the food was tasty, the nurses were attentive and that everything was being accomplished at the lowest possible cost.

The staff at CPC Olympus View Hospital knew from the start that Conte wasn’t an average patient. He’s the boss--chairman and chief executive of Community Psychiatric Centers, a Laguna Hills-based chain of psychiatric hospitals that watches the bottom line with microscopic intensity.

Playing the role of both tough guy and tightwad has enabled Conte to perpetuate one of Wall Street’s longest-running success stories, leading CPC to 20 consecutive years of improved earnings.

CPC’s sustained success is particularly impressive given the disastrous fate that has met its neighbor and competitor, Comprehensive Care Corp. of Irvine.

Comp Care announced two weeks ago that it is selling its California assets in an effort to pay off creditors, after a disastrous merger attempt that failed in the 11th hour. The company has posted losses of about $10 million in the past six months alone, and its revenue has fallen 17%.

Analysts attribute CPC’s sustained success primarily to the hands-on management style of Conte and co-founder and former Chairman Robert Green, who recently resigned to manage a sister company.

Financial World magazine recently named Conte one of its “CEOs of the Decade.” One reason is his attention to detail--he gives each of CPC’s 49 hospitals nationwide at least one thorough checkup a year.

“I stay in the hospital. I sleep there that night. I have my meals there,” Conte said. “We’ve heard from competitors that we’re so cheap that we won’t stay in a hotel. But the reason I stay in the hospital is because I want to know what it is like.”

The result is that CPC dividend checks land in shareholder mailboxes like clockwork. For the third quarter ended Aug. 31, CPC posted a 19% gain in profit, to $20 million on revenue of $80.2 million. The company’s profit margin is an impressive 20%.

The mere mention of Conte or his company causes stock analysts to launch into song unsolicited.

“There is no other company in this industry that can match them,” said Carl Sherman, analyst with the New York brokerage of Oppenheimer & Co.

CPC and Comp Care got started in the late 1960s, each mining its own profitable niche. CPC focused primarily on patients with mental illness; Comp Care tended to alcoholics and drug addicts, primarily through its CareUnits.

Over the years, the differences between the two companies blurred somewhat--CPC has chemical dependency programs and Comp Care has several psychiatric hospitals, including Brea Hospital Neuropsychiatric Center.

Each company earned a spot on the New York Stock Exchange and built headquarters practically within walking distance of one another in Orange County.

By the 1980s, the two companies had something else in common--both were under siege because of belt tightening by insurance companies and increased competition from new companies that wanted in on a growth industry.

CPC overcame the obstacles. Comp Care succumbed to them.

Financial analysts say the basic difference between the two companies boils down to monetary policy. CPC spends money like a person raised in the Depression--something as commonplace as advertising is considered an extravagance and borrowing money is only done as a last resort. Comp Care, on the other hand, behaved like a free-spending child of the “Me” generation.

“These companies are day and night. Community Psychiatric is the best financially managed company I deal with,” said Peter Sidoti, analyst with the New York brokerage of Drexel Burnham Lambert. “Comp Care was the exact opposite situation.”

The hospital inspection is a typical example of Conte’s hands-on style.

After his visits, Conte gives every hospital administrator a report card of sorts, with a score ranging from 0 to 10. He is a tough grader.

“Our hospitals in my grading have never been higher than a 9 or lower than a 2 1/2,” said Conte. “The average would be 6. And on the 2 1/2 we had an instant execution of the administrator.”

He even complains about hospital food. “It irritates the hell out of me to go to a hospital that has lunch prepared by 10 o’clock in the morning or dinner by 3 o’clock,” Conte said.

Being involved in day-to-day operations has characterized Conte’s career. Nearly 30 years ago he was the administrator of a 34-bed psychiatric hospital in Alhambra.

“I lived there for six months,” Conte recalled. “During the day I was the administrator and business manager, and at night I was the occupational therapy director. And on the weekends I was the cook.”

Personnel is a critical area targeted for cost savings by the company’s bean counters. Every day, CPC hospitals call headquarters to report employee and patient counts and the Laguna Hills office makes regular adjustments, adding or deleting personnel by relying on the company’s substantial force of free-lancers.

The hospitals themselves are built with a lean staff in mind--the nurses’ stations are situated so that staff can look down two wings at once, and meals are generally served in a cafeteria rather than in the patients’ rooms.

“We are the leanest hospital company in regard to staffing and I think our profit margins show it,” Conte said. “There is literally not a hospital in the country that I walk into with the possible exception of some of our own that I couldn’t cut staffing. . . . Just walk around a hospital once and see how many employees are sitting around and just talking to one another.”

The purse is so tight at CPC that administrators often must get corporate approval for any expenditures above $100.

“There is a conservative thread that runs throughout the company,” said Thomas Dougherty, former administrator of the CPC Horizon Hospital in Pomona.

For instance, CPC is far more cautious with its expansion plans than Comp Care ever was.

“For almost five years, Community Psychiatric didn’t grow,” Sidoti said. “They were careful and opened in markets only where they needed to be. Comp Care didn’t do the same kind of homework.”

CPC builds its new hospitals with cash generated from existing operations; Comp Care borrowed heavily. CPC had only $30 million in long-term debt as of Aug. 31. Comp Care--which brings in substantially less revenue than CPC--had $72 million in long-term debt as of May 31 and has not paid back $25 million that was due Oct. 18.

If CPC “couldn’t build the facilities out of cash flow, they didn’t build them,” said Dougherty, now an administrator for Spectrum Health Services in Placentia. “They had more conservative growth and a more steady, plodding growth.”

Borrowing the funds to build could increase costs by as much as $100 per patient per day, according to Conte.

Making matters worse, much of Comp Care’s business was with existing hospitals that it didn’t own. The company often contracted with hospitals to run chemical dependency programs for them. They lost many of those contracts, not because their care wasn’t good but because some of the hospitals figured that they could run similar programs and make more money for themselves.

So when the health-care industry began to feel pinched in the 1980s, CPC was in a far better position to control its destiny than was Comp Care.

“Comp Care was vulnerable because of its contract business and a lot of hospitals went to school on Comp Care,” said David Langness, a former Comp Care spokesman.

CPC’s marketing strategy is cheaper than Comp Care’s too. Comp Care blanketed newspapers and television stations with riveting ads, showing the grieving family of an alcoholic at the man’s graveside.

“There were years we spent $12 (million) to $15 million on just television,” Langness said.

CPC doesn’t advertise. “I’m sure you’ve seen their ads as everybody else has on TV,” Conte said. “You’ve never seen ours.”

Again, he calculates the cost savings as high as $100 per patient per day.

CPC gets it clients through word of mouth, physician referrals and an innovative community education program. For instance, CPC recently held a workshop for clergy titled “How to Deal With Remorse.”

The idea behind the program is that the participants will send hard-to-handle cases to the expert care of CPC. “It’s a selfish interest as well as community education,” Conte said.

The penny pinching at CPC has some detractors, including people who have labored under the system. During the past two years, both CPC and Comp Care were the subject of complaints by former employees who claimed that the companies put profits ahead of patient care.

CPC’s facility in Santa Ana was hit with six complaints during the first five months of 1988, more than any other other major psychiatric hospital in Orange County at that time. The allegations ranged from sexual molestation among patients to a shortage of nursing staff and incomplete record keeping.

The state Department of Health Services said it has received further complaints about CPC in Santa Ana since then. Conte said he has installed new management and said at least some of the allegations were unfounded.

Comp Care’s Brea psychiatric hospital is the subject of two lawsuits by former administrators who claim that inadequate patient care resulted in a series of tragedies, including an unattended patient’s death from a drug overdose, an attempted suicide and a homosexual gang rape of a teen-ager. Comp Care has denied the charges in the past, saying they are unfounded.

Executives at Comp Care did not return repeated requests for an interview.

The majority of former CPC administrators interviewed said the company’s treatment is better than adequate and worth more than what the company charges for it, which is usually less than the competition.

“They are not the Cadillac of the industry,” said one former executive. “They are more like Volkswagen.”

Conte insists that CPC doesn’t shortchange patients and points to the industry’s regulator as proof. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, which inspects the nation’s hospitals, continues to renew all of the accreditations on CPC’s facilities.

“Profitability was not at the expense of the patients and their problems. They just run a very tight ship, very focused, very much bottom-line oriented,” said another former administrator. The company patient-to-nurse ratio of 1.87 is around the industry average.

Further evidence supporting Conte’s assertion of quality care is the company’s open enrollment program for physicians. Once they meet CPC’s qualifications, doctors are given admitting privileges at CPC facilities but they come and go as they like. They are not staff physicians and have no vested interest in ensuring that large numbers of their patients use CPC.

The average CPC patient is a 35-year-old woman from a middle- to upper-class background suffering from depression.

The length of time that she spends in a psychiatric hospital these days is diminishing because of better medication and stricter insurance requirements.

Yet companies such as CPC--and until recently Comp Care--continue to open new facilities. The reason behind this seeming paradox is twofold: Psychiatry is receiving unprecedented public acceptance, and it’s far more precise than in the past. So more and more people are seeking help.

Because CPC has doubled the number of hospitals that it owns during the past several years, financial analysts think that Conte can continue his magic act of improved earnings. The occupancy rates at some hospitals are low because they’re new. As rates climb, revenue and profit will grow.

“During the past three years, we doubled our size. We overbuilt a number of facilities specifically ahead of their time. So now as we fill them, we become increasingly profitable,” Conte said. The best part: Shareholders know the hospitals are already paid for.

Comp Care, meantime, is trying to hold off creditors through its fire sale.

“Comp Care wanted to hit a home run today,” Sidoti said. “Community Psychiatric has been hitting singles for 15 years.”

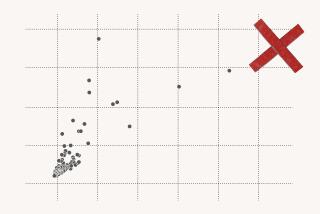

COMP CARE AND CPC: OPPOSITE CASE HISTORIES

COMMUNITY PSYCHITRAIC CENTERS

CPC: Alhambra Hospital

CPC: Belmot Hills Hospital

CPC: Fairfax Hospital

CPC: Heritage Oaks Hospital

CPC: Horizon Hospital

CPC: Rancho Lindo Hospital

CPC: San Luis Rey Hospital

CPC: Sierra Gateway Hospital

CPC: Sierra Vista Hospital

CPC: Vista Del Mar Hospital

CPC: Walnut Creek Hospital

CPC: Westwood Hospital

Comprehensive Care Corp

Starting Point, Oak Avenue

Starting point, Grand Avenue

CareUnit Facility

Crossroads Hospital

Woodview-Calabasas Hospital

Sutter Center for Psychiatry

Sources: Community Psychiatric Centers and Comprehensive Care Corp.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.