BOOK REVIEW : Historical Tale That Is Still Relevant During the 1990s

Lightning in July by Ann L. McLaughlin (John Daniel: $9.95; 179 pp.)

If you’re under 40, this will be a historical novel. You won’t remember the steamy Julys when swimming pools were closed, movies were forbidden, and school started late because of the polio epidemics. Despite all the precautions, there was always someone--a grade or two ahead or behind, perhaps a teacher--who came to class on crutches.

By 1955, the word polio wasn’t automatically followed by epidemic, but by vaccine. A paper cup, a quick gulp, and summer was returned to children, better than ever before.

“Lightning in July” takes place in that watershed year, the last time there was a major outbreak of the disease in America. In 1955, in a final burst of capricious virulence, polio swept the Northeastern states, affecting as many young adults as children.

The hero and heroine of this novel are victims: Dan Lewis, a graduate student at Harvard, and Hally Blessing, a gifted flutist making her debut at an outdoor concert with the Boston Pops. He’s in the audience that night, taking a break from the academic grind, watching her. By morning, both are patients in Wahl Hospital. Antiquated and shabby, Wahl has been turned into an emergency facility for the unprecedented number of polio cases in the city.

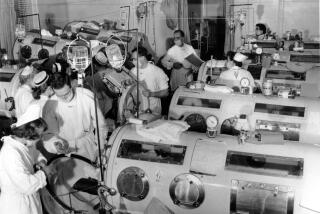

The virus was erratic and protean, attacking different victims in various guises. Hally’s case is bulbar, seizing the muscles of the neck, jaw and, tragically often, the breathing passages, but leaving the arms and legs intact. With bad luck, victims of bulbar polio ended up in iron lungs--a phrase that has happily become obsolete, but then was still a nightmare word, spoken in whispers.

Though Hally escapes that fate, the disease damages her speaking voice, her breathing and her lips, demolishing the work, the dedication and the dreams of a lifetime.

Dan has the more familiar variety, paralyzing his legs and weakening an arm and his abdomen. There is no way of knowing whether the disability is temporary or permanent.

Their rooms adjoin, and as soon as Hally is mobile, they meet and gradually, inevitably, fall in love. Miraculously, the author avoids the artistic pitfalls of her plot and setting. Though every crack in the drab walls is noted and you can smell the disinfectant and taste the watery soup that Hally must learn to “drop” down her paralyzed throat, the novel never slips into bathos.

While the characters suffer agonies of self-doubt, they don’t succumb to the despair that surely must be a concomitant of a disease for which the only prognosis was never more than “wait and see.”

Dan and Hally spend nine months in that hospital, in the course of which we know not only them, but the attending doctors, nurses and orderlies. We meet other patients--some defiant, some bitter, others relentlessly optimistic.

Dan and Hally are in the middle range; pragmatic, cooperative, but fortunately, not martyrs. They fight the disease, the uncertainty, and from time to time, they fight each other, and it’s the battles that save the book from becoming an inspirational tract on overcoming tragedy with fortitude.

It is tragedy to see the future recede, to watch your horizons shrink from the whole world to the view from a single window, to be forced to accept limitations and restraints half a century too soon. If the subsidiary characters seem mere collections of traits, consider how few options a hospital offers its inmates.

There are intimations that this book is at least in part autobiographical, hints that cannot help altering the reader’s reaction. We’re tempted to sympathize and to suspend standards that apply to fiction but seem irrelevant to life. How many “Magic Mountains” do you get in a century?

Though the book is candid, the process of turning the events into a novel inevitably works as a filter. The pathology is presented quickly and factually, curtains drawn around fear and rage as they’re drawn around hospital beds. Slowly and incompletely, Hally and Dan recover, transforming “Lightning in July” into a story of love in a crucible. In 1989, there’s nothing dated or irrelevant about that.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.