AIA Grants Rare Honor to ‘Genius’ Behind the Lens

When Marvin Rand took his first photo of Watts Towers in 1953, Sam Rodia was putting the finishing touches to his 30-year masterpiece of reinforced cement, seashells, 7-Up bottle bottoms and crockery shards.

“I saw this stocky, little guy hanging on the tallest tower, 90 feet or so up in the air,” Rand recalls. “All he had pinning him there was a metal hook tucked through his belt and hooped over one of the tower’s rungs. His energy was amazing, and so was his imagination. Once he told me his third wife was buried under the tallest spire.”

Thirty-six years later, Rand is completing a 1,500-photo survey of the Towers, commissioned by the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department. This photo survey is the first systematic record ever made of Rodia’s creation, now undergoing a program of careful restoration.

The survey brings Rand’s distinguished career in architectural photography full circle. In recognition of four decades of excellence, the national headquarters of the American Institute of Architects in Washington has awarded Rand an honorary membership--a rare distinction for a photographer.

“Rand is a genius when he reads the lens behind the black cloth,” architectural historian Esther McCoy wrote in a letter sponsoring Rand’s honorary AIA membership. “He is one of a half-dozen (architectural) photographers who have set the standards for this relatively new profession.”

As much as any other local lensman, Rand has defined the special character of Los Angeles architecture with a distinctive sensitivity and artful subtlety.

Cesar Pelli, architect of the Pacific Design Center, described Rand as “one of the most sensitive and dedicated architectural photographers I know. His work gets better and better.” Frank Gehry talked of Rand’s “tireless, beautiful and loving documentation of many of California’s landmark buildings. His creative craftsmanship is of the highest order.”

Architectural historian Jean Paul Carlihan lauded Rand’s “extravagantly beautiful prints--sharp, rich in tone, and breathtaking in their depth of field. They convey, as well as any two-dimensional form can, the presence of architecture as an art of forms in space.”

Rand characterizes his own style as “essentially self-effacing. The photos serve the architecture, not my ego.”

When he first sees a building, Rand takes a hard look, then walks away, “to collect my gut impressions of the architecture, and sort out its salient visual impacts.” He discusses the design with the architect, to understand the ideas embodied in the finished work, and slowly develops a “philosophy” for each shoot that best expresses its intrinsic qualities.

Despite Rand’s reverence for the design and his personal modesty, he does not allow the architect to dictate the photography.

“You have to follow your own instinct,” he said. “Too many young photographers today allow the architect to tell them how to see, and that’s a bad mistake.”

Working with architect Louis Kahn in a shoot of the Salk Institute in La Jolla in the 1960s, Rand learned that a designer and a photographer may have differing yet complementary views. Kahn looked at the Institute as a formal composition of solids and voids, but Rand saw it as intricate play of light and shadow over the surfaces and volumes of a building. Though their approaches differed, the legendary architect enjoyed Rand’s dramatic images.

“It was never an ego clash,” Rand said.

The famous architectural photographer first trained in advertising. But in 1951 Esther McCoy introduced him to John Entenza, editor of Arts and Architecture magazine, who initiated the innovative Case Study House program.

“Soon I was deeply involved in what was going on in L.A. architecture in the exciting 1950s,” he said.

In the 1950s Rand became a regular at meetings of the Design Group, a circle of avant-garde architects, artists and graphic designers that included Charles and Ray Eames, graphic artists Alvin Lustig and Saul Bass and designer Craig Ellwood.

They frequented Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood, where young experimental artists such as Ed Kienholz and Ed Ruscha hung out.

“It was a wonderful period,” Rand said. “We had great parties at the Beanery, and fierce fights about art, architecture, sex and life.”

Rand photographed Case Study Houses designed by Ellwood and Rafael Soriano. He also worked with Eames and Welton Becket. In 1957 and 1968 he produced catalogues for exhibits on the work of Irving Gill and Rudolf Schindler at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and made a major contribution to McCoy’s classic book “Five California Architects.”

“In those early years, architectural photographers in Southern California were thin on the ground,” Rand said. “Julius Shulman, Maynard Parker, Bob Cleveland and me--that was more or less it. We each had our own style, but we all shared a devotion to the avant-garde.”

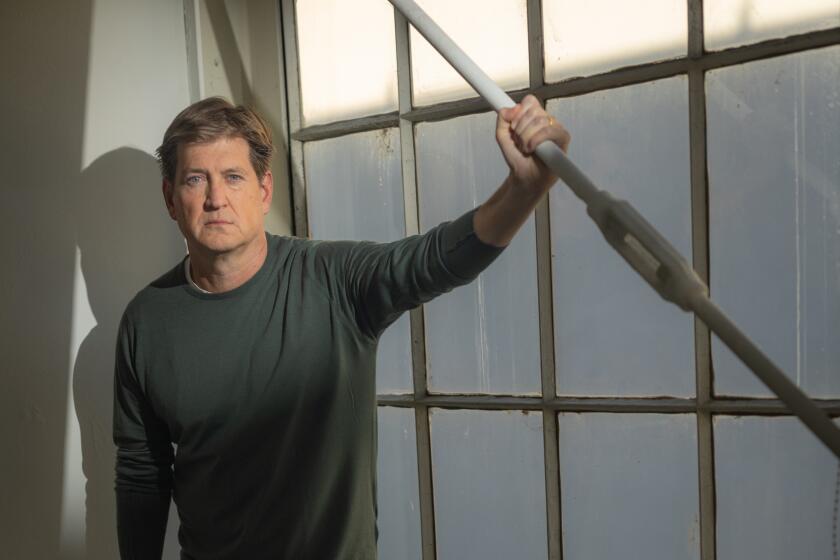

A small, round-faced man with alert brown eyes shielded by oversize spectacles, Rand and his second wife, weaver Mary Ann Danin, share a Venice studio where he has his own color-processing equipment.

“I don’t trust commercial labs,” he said. “Much of the art of photography happens in the processing, and I must have control over all of it.”

Though he recently underwent heart surgery, Rand still races a 14-foot sailboat in regattas, with one of his two sons as crew.

Rand grew up in the City Terrace area of East Los Angeles. His father was a furniture maker and his mother was a fashion designer who worked in the city’s embryonic garment industry. From her, Rand says, he learned a respect for “the texture of things, the feel of surfaces, the sensual quality of every kind of material.”

With his deep reverence for design, Rand decries the current trend that makes the photo of the architecture almost more important than the building itself.

“The pretty picture has all too often become the end product of the design process,” he said, “rather than serving as a record and interpretation of the architecture. This is a trivialization of the designer’s art.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.