FCC Holds Fate of L.A.’s Only Black TV Outlet : Television: Stillborn Channel 68 may be sold to Spanish-language religious group for $2.3 million.

Five years ago, Los Angeles was promised its first and only television station owned and operated by blacks. Today, much to the consternation of black community leaders, the stillborn UHF outlet may be on the verge of being turned over to an evangelical Spanish-language organization.

The Burbank-based Hispanic Christian Communications Network says it has obtained the approval of all but one of the board members of the Black Television Workshop for the network’s proposed $2.3-million purchase of KEEF-TV Channel 68. At a news conference Tuesday, it will ask minority community leaders and viewers to join in asking the Federal Communications Commission to promptly approve the sale, first proposed last March.

Ignoring staff recommendations that the transfer be rejected, recently appointed FCC Mass Media Bureau Chief Roy Stewart has met with the key principals and replaced the attorney handling the government’s case. The FCC declined to comment on this case because it is pending, but sources involved in the case say Stewart and other Bush appointees are anxious to rid themselves of the 2 1/2-year-old KEEF headache and move on to other business.

If consummated, the deal will shatter the dream of black entrepreneur Booker T. Wade Jr., whose bizarre legal battle with federal authorities and fellow Black Television Workshop board members has kept the non-commercial station silent since August, 1987.

Although the prospective new owners say that they will welcome “family oriented” programming toward any and all minorities, the Hispanic Christian Communications Network’s Channel 68 would be a far cry from the black media powerhouse that Wade first outlined in a 1984 publicity blitz.

Originally slated to sign on in 1986 as KDDE-TV--the call letters were later changed for unexplained reasons--KEEF was conceived as the flagship of a national program service that would serve as a rare entry point through the television industry’s alleged de facto color barrier.

Wade described the venture at the time as the brainchild of “everyday” people who were tired of the “Anglo-cultural and British-cultural bias” of the Public Broadcasting Service. The black-produced PBS specials “Eyes on the Prize” and “The Africans” were great, he said, “but they are just not enough.” Wade did not return numerous calls regarding this article.

Except for Washington-based Howard University’s WHMM-TV, there are no black-owned public TV stations and only a few production companies. Wade persuaded community leaders, financial backers and the FCC that Black Television Workshop would yield a continuing stream of black programmers and programming.

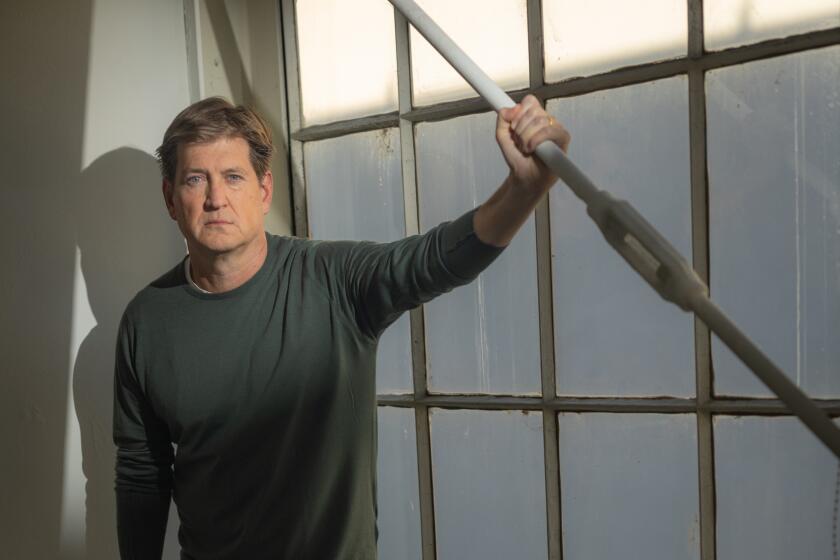

But not only has Wade been unable to deliver on those promises, the 43-year-old attorney and former FCC staff member also has spent the last two years fighting attempts by several original workshop board members to replace him as KEEF’s president because of what they charged was his mishandling of the station. The dissident faction is led by Mary V. Woodfork, a Culver City medical assistant who said she first met Wade through a friend who had been dating him. (Woodfork is the only board member opposed to the sale to Hispanic Christian Communications Network.)

Results of an extensive FCC investigation into Wade’s conduct may never be made public if the Hispanic Christian Communications Network persuades the regulatory agency to let it take over the station before a long-postponed hearing on the charges is convened. The FCC may simply walk away from the case without ever adjudicating the pending accusations against Wade, which include charges of administrative mismanagement.

Wade, in turn, may never have a chance to press his counterclaim that the FCC has unfairly, willfully and perhaps illegally forced his project to the edge of bankruptcy.

In a highly unusual but little-publicized action, the FCC has kept KEEF off the air for 27 months while it figures out who should control the station.

“What the FCC is doing is unprecedented in the history of television,” Wade said last year, before cutting off all contact with the media. “The charges against me are false and I am confident I will prevail against them.”

Wade characterizes the FCC’s interim shutdown as a baffling and frustrating abuse of regulatory power.

The prolonged government silencing of KEEF has drawn formal protests from Assemblywoman Gwen Moore (D-Los Angeles) and other prominent black politicians, including state Sen. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) and Mayor Tom Bradley.

Moore is described by an aide as “very concerned” about the loss of KEEF on behalf of her mostly black South-Central Los Angeles constituents. The legislator, who calls public media “a potential tool for social change,” has tried unsuccessfully to get the two KEEF factions to reach a settlement.

According to internal FCC memoranda obtained by The Times, Woodfork and two other members of the original board--its first chairman, Clint Wilson II, associate dean of the School of Communications at Howard University, and Gary Cordell, an insurance administrator in Palo Alto--have leveled a number of allegations about the propriety of Wade’s management practices.

While Wade and his Washington-based attorney, Stephen Yelverton, admit to a few unintended technical violations of agency procedures, such as the tardy filing of certain documents, they contend that “factual misstatements” by Woodfork have misled FCC staff.

Black Television Workshop is not Wade’s first media venture. After leaving the FCC in 1980, he and some partners won the licenses to a string of low-power TV stations in the Southwest and created the Music Channel, a music-video service targeted at older women. It never caught on, however, and was out of business by 1984.

As the music video network foundered, Wade conceived and organized Black Television Workshop as an applicant for the last vacant full-power channel in Los Angeles, Channel 68, a frequency left vacant by KVST-TV, a viewer-supported public station. He recruited eight board members, seven of whom also were principals in his low-power TV applications--including Woodfork, Wilson and Cordell.

When the station’s construction permit was finally approved in 1983, Black Television Workshop chairman Wilson told The Times that its facilities would support a state-of-the-art training center, seven hours of daily programming and a staff of six. Construction costs were put at $3.15 million, with an annual operating budget of $1 million. The money would come from viewer donations, foundation grants and the lease of excess studio space or air time, Wade said.

KEEF finally signed on in April, 1987, with a limited slate of educational programs. On Aug. 8, an unexpected shutdown order arrived from the FCC. The agency was acting on a series of complaints from Woodfork that had begun in June.

Woodfork has said that her concerns developed over several months and that the FCC’s decision to take the station off the air was based on a series of alleged improprieties by Wade in his capacity as president of Black Television Workshop. She says she was unable to raise them with the board of directors because by then Wade contended that she, Wilson and Cordell were no longer on the board and had been replaced. The FCC has never ruled on whether the new members were seated legally.

In explaining his shutdown action at the time, Mass Media Bureau deputy chief Rod Porter cited “complex issues” as to “who actually controls the station, whether or not the station is going to be operated consistent with requirements for non-commercial operators and alleged improprieties (involving Wade).”

In sum, he later told Broadcasting magazine, “the right question is: Should the station have been on the air in the first place?”

Yelverton dismisses Porter’s concerns as groundless and “flaky.” He says that the FCC, by keeping KEEF dark and allowing unsubstantiated attacks on his client’s character to circulate, “has effectively destroyed a fledgling station.”

Indeed, the KEEF blackout has kept scores of station vendors in limbo, unable to obtain the more than $1 million collectively owed them.

The largest single creditor is Cerritos-based Radio Telecom & Technology, with about $400,000 invested in KEEF’s equipment. Under terms of a contract signed by Wade, the electronics firm is the owner of the KEEF transmitter.

“We have been hurt severely,” says Lou Martinez, RT&T;’s founder and the inventor of T-NET, an experimental data distribution system that would have used portions of the Channel 68 signal unseen by viewers.

Martinez tried to mediate a settlement among the feuding parties but grew tired of what he calls the FCC’s “double talk.” In July, RT&T; joined with Hispanic Christian Communications Network in filing a civil suit in Los Angeles Superior Court against the Black Television Workshop board of directors, aimed at resolving the control question and expediting the sale.

Whatever animosity exists toward Wade, even his detractors question the wisdom of unplugging KEEF while the control issue remains unsettled. The FCC’s usual approach is to keep stations operating whenever possible, particularly during internal disputes.

Charles Firestone, a Los Angeles attorney who left the FCC 10 years ago to head UCLA’s communications law program, blames the FCC for creating a “Solomon situation” that “lets the baby die while they try to figure out who the proper parents are.”

“We’re talking about a black-owned UHF public-TV station,” Firestone said. “This is the one category (of broadcaster) that needs to be kept alive.”

Wade still lives in Los Angeles and is a consultant to the Minority Television Project, which seeks to win control of San Francisco’s non-commercial KQEC-TV from co-owner KQED-TV.

Woodfork, now acting as her own counsel, has kept her job in a physician’s office and spends many of her free hours working on the Black Television Workshop case.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.