L.A.’s Southwest Museum Missing $1 Million in Art

Officials of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles have compiled a list of 65 American Indian artworks that are missing from its collection and are being sought by federal authorities.

The items include rare textiles, baskets and dolls whose total value in today’s market is estimated by dealers at more than $1 million.

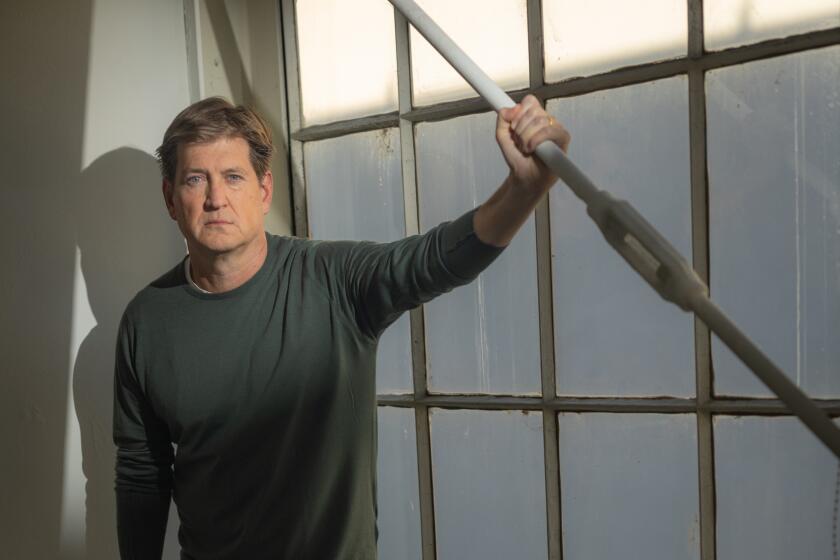

A shortfall in the collection and an FBI investigation into it were made public six weeks ago. At that time the museum’s executive director, Jerome Selmer, put the loss at “a few more than 25 but not a huge number of items” and would not estimate their value.

Last week, a description of the missing pieces was circulated to dealers by the Foundation for Art Research, a national organization that distributes information about stolen, missing and fake artworks. Selmer confirmed Monday that the Southwest Museum is the unnamed museum in the foundation’s illustrated flyer.

The museum on Mt. Washington houses one of the country’s best-known collections of Indian art. The investigation has been the talk of the American Indian art world, which is centered in New Mexico and Arizona.

The investigation was sparked by an inventory taken shortly after Selmer became executive director of the museum about eight months ago. When the shortfall was discovered, the FBI was called in.

Although Southwest Museum officials will not characterize the disappearances as thefts, several dealers interviewed in the Southwest United States said they had knowledge of the FBI confiscating items from collectors that allegedly were from the museum collection.

The most valuable items on the missing list are 19th-Century textiles. A Navajo poncho-style serape on the list is so rare, according to Joshua Baer, who operates a well-known gallery of American Indian artifacts in Santa Fe, N.M., that it could fetch as much as $150,000 in today’s active art market. Joe Carr, a dealer in Navajo textiles in Santa Fe, said that, judging by recent auction activity, blankets on the list could, depending on their condition, be worth $40,000 to more than $150,000 each.

Baer estimated that baskets on the list range in value from $2,000 to $30,000, that Hopi Indian dolls are worth from $5,000 to $15,000 and that ceramic jars are each worth about $10,000.

Also listed as missing were 11 portrait paintings of American Indians by American artist Maynard Dixon, best known for his landscape paintings. Last week a Dixon painting similar in size to one of the paintings missing from the Southwest Museum sold at auction at Sotheby’s for $49,500.

The list was sent out last week as a special “Missing Art Alert” to about 1,000 subscribers to the publications of the New York-based Foundation for Art Research. The document did not identify the museum by name, saying only that it was “a major anthropology museum in the Western United States.”

Aside from acknowledging that the museum was the Southwest, Selmer would say little about the investigation.

He confirmed that the FBI had recovered some of the items but would not say which ones, how many or where they were located.

Patrick Houlihan, who was director of the Southwest Museum from 1981 until 1987, offered an explanation for what happened to some of the missing items.

Houlihan said in a telephone interview Monday that, when he was director, some of the pieces were traded for other objects deemed more appropriate for the collection. The trades were made in accordance with museum board policies, he said, noting, “It was consistent with past practices.” He would not identify any of the artworks.

Asked if those trades were noted in paper work that would be in museum files, Houlihan said, “I think that’s true.”

Houlihan is credited with bringing modern museum practices, including a computerized inventory, to the Southwest Museum. He is now executive director of the Millicent Rogers Museum near Taos, N.M.

In the interview, he said he has not been contacted by the FBI or the museum about the investigation. “I’ve been taking a lot of heat for this” because of speculation in the art world about his role in the disappearances, he said.

He said his lawyers had contacted museum officials about the matter, but he would not say what those discussions were about.

Houlihan’s account of art swaps ran counter to the recollections of two other ex-employees.

Steven LeBlanc, who was the curator of archeology under Houlihan, said he did not recall any trades concerning American Indian artifacts. “It was my understanding we were not in the trading business at that time,” said LeBlanc, who left the museum last year and now works with Questor Computer Systems, a Pasadena company that installs computerized inventory systems in museums.

“There were some trades of items not considered appropriate for the museum,” LeBlanc said, “items that had been collected and stored over the years but had nothing to do with American Indian artifacts. Persian rugs, paintings of somebody’s mother, that sort of thing.

“But if there would have been trades concerning American Indian items, I think I was in a position to have known about that.”

Claudine Scoville, collections manager and registrar at Southwest from 1982 until 1987, said she processed the paper work surrounding the departure or arrival of each object at the museum.

“I was not aware of any Native American pieces that went out when I was there,” said Scoville, who is now collections manager of the Arizona State Museum in Tucson.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.