The Art and Science of Cinematography : Academy Awards: The work of the five nominated directors of photography is assessed by their colleagues.

Every year has its outstanding movie images, those visual moments that linger in the mind long after the credits have rolled. Somehow, Michelle Pfeiffer slithering on a grand piano in a clinging burgundy dress singing “Makin’ Whoopie” to piano player Jeff Bridges in “The Fabulous Baker Boys” comes to mind.

But the scene stood out for reasons other than the way Pfeiffer takes to burgundy. It was the way the camera, under the supervision of Oscar-nominated cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, captured her image, with a balance of shadow and light and a painterly use of colors that made the scene as playfully sultry as the song’s lyrics.

As veteran cinematographer William A. Fraker (“Heaven Can Wait”) explains it, the film’s cameraman “put the background lights on dimmers so that when the camera turns 360 degrees around the piano, he took the background out. Now, all of a sudden, (Pfeiffer) is the most important thing on the screen. You have only an illusion of people in the background.”

This is the kind of artistry academy cinematographers say they look for when nominating works for Oscars--images created through movement, lighting, composition and color that help a director tell his story.

In this article, the first in a series spotlighting the nominees in the “technical” categories of the Academy Awards, we asked several directors of photography--”DPs,” as they’re known in the trade--to explain why the work of the five nominated cinematographers merited special praise.

The nominees for best cinematographer in 1989 are Ballhaus, Freddie Francis (“Glory”), Robert Richardson (“Born on the Fourth of July”), Mikael Salomon (“The Abyss”) and Haskell Wexler (“Blaze”).

Opinions about the images of these films vary among their peers, depending on what their own interests are. Fraker, for instance, acknowledges that he is a “lighting man,” meaning that he is more impressed by work done under artificial lighting than in daylight.

John Alonzo (“Norma Rae”) thinks lighting is over-emphasized and says there is a prejudice among motion-picture academy members against daylight cinematography. “That’s why ‘The Black Stallion’ was overlooked several years ago,” he says. “Well, God may have lit the horse for you, but you’d better know how to shoot him.”

The “prettiness” of images is what often brings moviegoers’ attention to the camerawork. It also has that effect on fellow cinematographers, too, which explains the dominance of cinematographers of epic-scope movies in that Oscar category. Says Jan De Bont, who shot the current “The Hunt for Red October”: “The hard part (of cinematography) is to light a scene in a dramatic way that supports the story. And that doesn’t necessarily mean beautiful images.”

Vilmos Zsigmond (“The Deer Hunter”) admits that “many times, a cinematographer makes things too pretty. You have to fight yourself not to.”

Cinematographers have different feelings about the style of camera use. Some say that with really good camerawork, you get so involved in the story, you aren’t aware of the camera. Others say you should be aware of it.

“In Fellini’s ‘8 1/2’ or Welles’ ‘The Magnificent Ambersons,’ you are always aware of the camera,” says De Bont. “To make the (camerawork) invisible, to me makes a movie bland.”

Zsigmond says the current slate of Oscar-nominated cinematographers reinforces his feeling that “the level of cinematography is higher than ever. There’s more natural lighting. We have better cameras, lenses and film stock.

“More importantly, the taste of audiences is improving. They are demanding more realism. The demand is there and so are the tools to do it. So there’s no excuse.”

Here’s how some of their colleagues assess the work of this year’s Oscar nominees:

MIKAEL SALOMON

“The Abyss”

The images achieved here involved a logistic nightmare. Salomon had to marry his underwater photography with a myriad of visual effects.

“Underwater you lose contrast,” Zsigmond points out. “So the ways Mikael Salomon found to make everything interesting is remarkable. I’m sure academy voters thought it was fantastic that (filming underwater) can be done with such a natural approach. In the audience, you feel you’re there. Good cinematography brings the audience into the action.”

Fraker says Salomon’s use of “exterior backlighting, putting things in silhouette, gave a creative visual mood to objects under water. Since you don’t define that object, your imagination takes over. That involves an audience. It makes them work.”

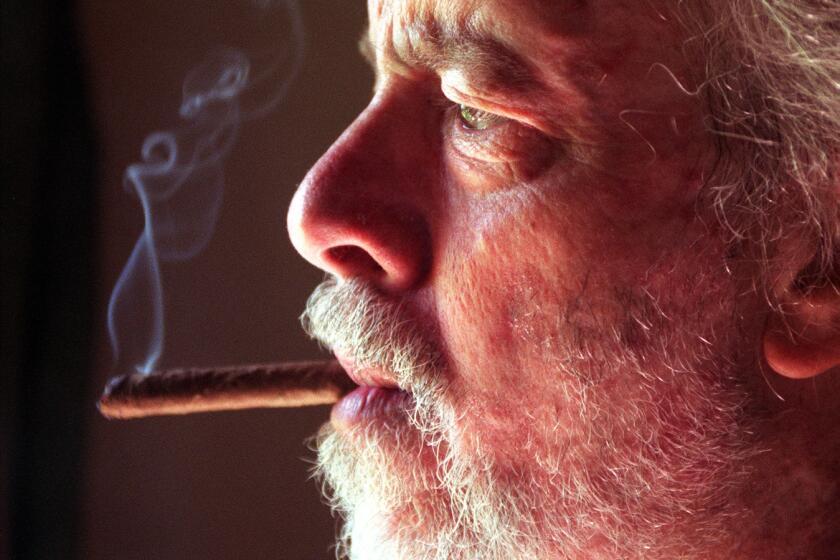

HASKELL WEXLER

“Blaze”

This is the fifth nominations for Wexler, a past winner for both “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and “Bound for Glory.” Yet, to the untutored eye, this nomination is the most puzzling.

The naturalistically lighted historical drama can boast of neither spectacular scenery nor visual razzle-dazzle. Yet Wexler’s work, which has already captured the American Society of Cinematographers’ award for best feature photography, has fellow DPs dazzled.

Conrad Hall (“Tequila Sunrise”) notes that, “while the camera did not call attention to itself, there are sweet and gentle nuances. You go from room to room and each has a different color. The movement of the camera is exquisite and the compositions flawless.”

Fraker too cites the film’s “changing visual look. That’s what separates the men from the boys--where you have 35 to 40 different sequences and moods in a picture, yet there’s a consistency in the dramatic visual level. One scene is in bright sunlight and another a smoky nightclub, but the tonal levels are the same.”

Brianne Murphy marvels at the emotional content of the lighting. “The lighting tells you where you are and how the characters feel.”

Alonzo says that all cinematographers had to have been knocked out by the film’s final shot.

“It began as a waist shot of a figure, then pulls back to show the entire city. To do that you have to suspend a radio-controlled camera from the belly of a helicopter. Haskell designed the shot so he could change the (camera) aperture, iris and speed. As it pulled back to see the entire town, he had perfectly exposed frames. It’s quite a piece of work.”

ROBERT RICHARDSON

“Born on the 4th of July”

To work with the same director consistently, which occurred in the old studio days but is rare today, is a great advantage, and all the cinematographers interviewed for this story say this is Richardson and Stone’s finest collaboration.

“The camera told the (film’s) story with its movements more than any other film this year,” Zsigmond says. “You felt involved with the story. You were there.”

Says Hall: “I don’t think I’ve seen a scene as nicely designed as the one where Ron Kovic is looking confused as (his unit) pulls out of that village. The village has been destroyed, there’s noise everywhere, and wherever the camera looks it sees nothing.

“Yet its movements are so precise, you imagine what you’re looking at. It makes panic understood visually. Then a very close presence appears, backlit so it’s in silhouette. This makes it terribly understandable how Kovic made the mistake of shooting his own man.”

“Richardson is the most daring of all those nominated,” says De Bont. “The film moves like crazy. The longest shot lasts only five or six seconds. You’re taking part of the whole situation with the camera. You get inside the movie.”

De Bont also points to Richardson’s stylistic elasticity, which in corporated the romanticism of Kovic’s early childhood with shocking images in a rat-infested VA hospital.

MICHAEL BALLHAUS

“Fabulous Baker Boys”

Ballhaus came out of the German New Wave to become a top American-based cameraman, shooting such pictures as “The Color of Money,” “Working Girl” and “Broadcast News.” In this film, his lighting and compositions caught the eyes of academy voters.

Murphy says she was impressed with the way Ballhaus handled the light, the balance between the foreground and background. “You got the feeling of what was back there without it being lit.”

“Ballhaus is very good at creating moods with shadows and light,” says Zsigmond. “As with Dutch paintings, the exciting part (of a scene) is what is not lit. The cinematographer tries to create a mood to bring audiences into that atmosphere.”

Fraker appreciates Ballhaus’ lighting of his female star. “I’m a romanticist. If you take a movie star and put her on the screen, her face is 24 feet high. I don’t want to see flaws. It’s a matter of where you position your light.”

Alonzo, who recently filmed an ensemble cast of six actresses in “Steel Magnolias,” could appreciate Ballhaus’ handling of a film with multiple cast members, “how Ballhaus will use the camera to accentuate one individual in the frame, or two or three of them. Cinematography sometimes requires a delicate choreography.”

FREDDIE FRANCIS

“Glory”

Many cinematographers admit their branch of the academy tends to nominate exterior pictures with a big scope over more intimate films such as “Enemies, a Love Story” or “Dead Poets Society.” “Glory,” the story of a black regiment in the Civil War, is such a picture.

Those who like this film feel Francis’ composition within the camera frame and the effectiveness of his lighting were the key factors in the British cinematographer’s nomination.

Fraker calls Francis “a magnificent black-and-white man,” recalling his early films, “Room at the Top” and “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.”

“The images in ‘Glory’ remind me of a black-and-white film than any of the other (nominated films). He addressed himself to overcast skies and smoke and heavy backlighting and didn’t use a lot of fill light for the battle scenes. He didn’t have to show a bullet enter a body to create the effects of war.

“That’s what cinematography is all about--creating an illusion.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.