How a Killer Fell Through Cracks at Jail : Corrections: Inmate’s escape went undetected for three weeks. Sheriff’s officials blame it on human error and an overburdened lockup.

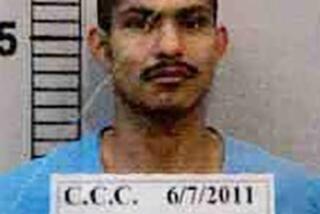

When inmate Victor Ramirez Castellanos slipped out of Los Angeles County Jail on March 22, news of his escape triggered the usual manhunt--but not until nearly three weeks later, when sheriff’s officials realized the convicted murderer had disappeared.

Castellanos has remained free since that morning, sheriff’s officials say, when he shed his handcuffs as he waited in line for a prison bus, rolled under the vehicle when it arrived and hid in the parking lot compound before fleeing undetected.

How could Castellanos--a street gang member who earned the nickname of “Mago,” or Magician, for his penchant for magic tricks--vanish so quietly from the Hall of Justice jail? And how could the Sheriff’s Department, which prides itself on an efficiently run jail system, lose track of an inmate?

Castellanos’ escape--and the 20-day delay that passed before deputies even knew he was gone--has turned into the jail system’s most embarrassing snafu. Sheriff’s officials now blame the security lapse on a combination of human error and the high-volume pressures of an overburdened jail system. In that system, large numbers of prisoners are constantly being moved and dozens of inmates known as “miss-outs” fail to appear each day for court hearings, forcing jailers to spend hours tracking them down.

According to Sheriff’s Cmdr. Mark Squiers, who heads the Inmate Reception Center at the Central Jail, sheriff’s investigators have learned that although Castellanos, 33, failed to board the prison bus to the center, an unidentified deputy mistakenly listed the transfer on the jail computer, an error that was never corrected and turned the missing inmate into a phantom prisoner.

When Castellanos failed to appear in court for a scheduled hearing the next day, his absence was listed as a “miss-out.” After he failed to appear four straight times over a three-week period, the alarm finally was raised.

“Were we embarrassed? Of course. That’s an understatement,” Squiers said. “Somebody should have been hollering right away.”

But nobody did.

“My initial reaction was: ‘He’s in here somewhere, we’ve just got to find him,’ ” recalled Capt. Lee Davenport, supervising officer at the reception center, whose deputies were first alerted about Castellanos’ disappearance.

“It’s not unusual for us to have a court miss-out, but we always find the inmate,” he added. “In this case, of course, we didn’t find him because he was gone.”

Miss-outs are a daily occurrence in the county’s huge jail system, where 23,000 inmates are crammed into a dozen facilities and about 1,700 prisoners from the Central Jail are bused each morning to scores of courtrooms scattered from Long Beach to the Antelope Valley.

The ritual begins around 1 a.m. each weekday. A computer center in Downey churns out a printed list matching prisoner names and locations with their court destinations for later in the day. A few hours later, passes are printed for inmates and, after breakfast, prisoners begin moving from the cells in a pre-dawn parade that sweeps them toward holding areas in the Inmate Reception Center. There, deputies check off each departing prisoner before an inmate boards a bus.

Inmates considered dangerous and high security risks are escorted individually. But most are handcuffed in pairs and linked to two dozen other shackled prisoners for the bus ride to court.

Each day, though, after all the buses depart, deputies are unable to account for a few prisoners.

On one recent morning, sheriff’s officials discovered 83 inmates were listed as miss-outs. As deputies searched for the absent inmates, some were found in time to be sent to court on later buses. Others, it turned out, had been transferred during the night to locations that had not been listed in the computer.

By the end of that court day, 19 remained as miss-outs. By the next morning, everyone had been found and his or her court appearance rescheduled. Davenport, whose Inmate Reception Center is the transit point for prisoners, said the intensive daily search for missing inmates is further confused by prisoners known to switch wristbands and alter passes--sometimes to escape, sometimes to miss court dates and sometimes simply to create trouble.

“Because of the movement in the jail, an inmate can get into a module that’s not his, go into a friend’s cell and sit there all day,” Davenport said. “Sometimes, that’s what they do to hide because they don’t want to go to court.”

Frank Zolin, county clerk and executive officer of the Superior Court, said no statistics are kept on miss-outs. But he estimated that they affect less than 1% of each day’s court cases.

Although the impact appears nominal, sheriff’s officials say some prisoners use miss-outs to try to short-circuit the legal process, missing deadlines that could force authorities to release them--even if only for a short while. Some inmates, for example, may try to avoid a court appearance because they know they are required to be arraigned within 48 hours of their arrest, Davenport said.

Others, said one Central Jail inmate who asked not to be identified, “just want to screw up the system and frustrate people, rag the department. Miss-outs don’t mean nothing to them.”

But inmates alone are not to be blamed for miss-outs, according to some critics who maintain that jailers can call out the wrong name or place an inmate on the wrong bus. And in the case of Castellanos, one county public defender added, a mistake by sheriff’s deputies has prolonged the freedom of a dangerous man.

Castellanos--also known as Victor Castrellanos and Victor Martinez Rodriguez--was convicted in 1988 of murder and was sentenced to Folsom State Prison. He was transferred from the prison to the County Jail in December, after an appellate court ruled that the sentence he received for the murder conviction had been unfairly lengthened because of a previous armed-robbery conviction.

Castellanos had been sentenced to 34 years to life in prison for the 1986 execution-style murder of Angel Herrera and the wounding of Herrera’s brother near the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

The slaying took place Dec. 13, 1986, after Castellanos and his companions confronted the 25-year-old Herrera, two of his brothers and two friends in the hallway of an apartment building. According to court records, Castellanos calmly described himself as the leader of a local street gang, then put a gun to Herrera’s head and fired a bullet into his temple.

As the frightened onlookers scattered, Castellanos shot Herrera’s brother, Raunel, in the back before climbing into a car and driving away. Angel Herrera died a few hours later. His brother survived.

Castellanos was convicted 16 months later of first-degree murder and two counts of attempted murder. In sentencing Castellanos, Superior Court Judge John H. Reid called the case “about as cold and calculating a murder as you’re going to find.”

When a subsequent hearing was ordered on the armed-robbery conviction, Castellanos was moved to the Hall of Justice jail for the court appearance. It was on the eve of one of those appearances that he escaped.

According to court records, Castellanos was listed as a miss-out on four consecutive court hearings from March 23 to April 11. Several times, Reid ordered his appearance, but then set new dates when he did not show up.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Ralph Shapiro, a prosecutor in the hard-core gang unit assigned to the case, said that, at first, there appeared to be nothing unusual about Castellanos’ miss-outs--especially after officials were assured Castellanos was in the prison infirmary.

“If I had thought anything at all was funny,” Shapiro said, “I would have called the jail and (had) someone immediately check it out.”

But it was not until after Castellanos failed to show up on April 11 that the Sheriff’s Department began a systematic lockdown of the jail system to find him. Six days later, the department admitted in a letter to Reid that Castellanos had escaped and asked the judge to issue the bench warrant for his arrest.

Castellanos remains at large, and the Sheriff’s Department has alerted authorities in the United States and in Mexico, where he was born.

Meanwhile, officials say they are confident they have taken precautions to discourage similar incidents.

Under the newly tightened system, deputies have been told to advise supervisors if an inmate has remained in the reception center more than 48 hours, a policy that would not have prevented Castellanos’ escape but would have alerted jailers to his disappearance.

“I don’t want to have to explain this again to the sheriff,” Squiers said. “I don’t want to do that. It was really hard to find the damn answer to ( this escape), to tell you the truth.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.