Feinstein, Wilson Vow Change for ‘90s in TV Debate : Campaign: Senator implies she would be a tool of legislators. She suggests he represents politics-as-usual.

Portraying a California yearning to recapture its promise, gubernatorial candidates Dianne Feinstein and Pete Wilson battled in a statewide televised debate Sunday, both contending they could best invigorate the much-criticized and often-stalemated state government.

While their exchanges were forceful and largely polite, Feinstein and Wilson did accentuate their differences: He aggressively implied she would be a tool of powerful Democrats in Sacramento and that he was better equipped to manage state departments in a fiscally prudent way.

And she suggested that Wilson was a symbol of politics-as-usual, less willing than she to forge ahead with change.

“The time has come for us to change, to step boldly into the 1990s to say that we can be the best, that we can stand the tallest, that we can solve our problems and that we need a new voice to do so,” Democrat Feinstein said in her closing statement.

“We can make our streets safe and we can clean up our environment. We can only do that if we have a leader and if the people are willing to follow that leader,” she said.

Republican Wilson, taking a similar tack, told viewers that California “can reverse that dropout rate. We can change young attitudes and change young lives.”

“I want a California of much longer graduation lines and much shorter unemployment lines, a California where no ambition is too great, no goal beyond the reach of any child,” said the incumbent U.S. senator. “I want them to be able to think they can lead a mission to Mars, or find a cure for AIDS or Alzheimer’s or breast cancer.”

In the debate, broadcast from the Burbank studios of KNBC-TV, Wilson used the theme of change to announce his support for Proposition 140, the November ballot initiative that would limit Assembly members to three terms and constitutional officers and state senators to two terms. Feinstein opposes the measure.

To illustrate what he called the deterioration of the California Legislature, Wilson cited the case of convicted rapist Lawrence Singleton, who hacked off a 15-year-old girl’s arms after raping her and leaving her to die. Singleton served seven years in prison, Wilson said, because the Legislature refused to stiffen criminal penalties.

“There should be an end to patience,” Wilson said of his support of Proposition 140. “It’s a sad thing. We’ll probably lose some talent. On the other hand we’ll get new blood.

“We will get some people who haven’t been up there for 50 years,” he said, a reference to Feinstein’s Democratic supporters, Assembly Speaker Willie Brown of San Francisco and Senate President Pro Tem David A. Roberti of Los Angeles.

“Well, senator, if you really feel you can’t handle Willie Brown or David Roberti, then stay in Washington,” Feinstein snapped back. “I’ll handle them.”

The Democrat also charged that the term-limitation measure, if approved, would leave a naive Legislature unprepared to fend off the advances of veteran lobbyists and bureaucrats.

“You don’t have term limits on lobbyists,” she said. “You don’t have term limits on bureaucrats. . . . I agree with President Reagan. I don’t believe term limits make sense.”

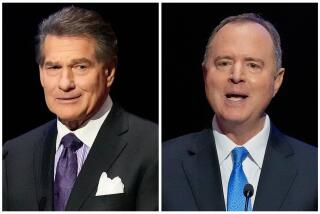

Wilson and Feinstein, both 57 and veteran politicians, stood at lecterns six feet apart during the debate. The former San Francisco mayor, standing on the television viewers’ left and wearing a purple suit, sounded hoarse as the debate began. Wilson, wearing a charcoal suit and a red tie, also appeared to lose his voice on occasion.

During the debate, Wilson repeatedly glanced down at the lectern, while Feinstein appeared to be reading notes written in ink on her hand.

Running even in recent polls and mindful of the potential importance of the debate to voters around the state, Feinstein and Wilson exchanged jabs immediately, using the opening question to assail each other. But neither appeared to land a knock-out blow or stumble markedly. Both candidates attempted to put forth the moderate images they present on the campaign trail, she a “tough but caring” politician and he a “compassionate conservative.”

Financial matters--campaign and personal--dominated sections of the debate.

Wilson, announcing that he would today release all of his income tax returns for the last 10 years, challenged Feinstein to do the same. She retorted that she had made 17 years of tax returns available earlier this year, and referred pointedly to Wilson’s persistent campaign criticism of her husband, investment banker Richard C. Blum.

“I don’t think there’s been any couple in American political history that’s made the kind of disclosure we have,” she said.

Wilson responded that his campaign had heard reporters complain about a lack of access to the couple’s financial records.

“If someone wants to see our information, they ought to take it up with me, senator, and not with you,” she replied.

Under questioning from a panel of reporters, Feinstein defended her recent decision to accept large campaign contributions, a move made possible when a federal judge threw out the state’s $1,000-per-person contribution limit. She said she had to accept large donations in order to remain competitive with Wilson.

“I’m running against a prolific fund-raiser,” she said. “. . . I lose the election if I can’t compete on television--that’s the bottom line.”

Feinstein, ticking off items she frequently cites in her campaign, said Wilson had received more donations from the savings and loan industry than any other member of Congress, and added that he was high on the list of politicians who had received contributions from agriculture, chemical concerns and oil company officials. Wilson countered by criticizing Feinstein for taking a $150,000 contribution from the California Highway Patrol officers’ union after the spending cap was lifted.

“Dianne, I am truly shocked that you would be so blind to such a gross conflict of interest,” he said, noting that as governor she would have to approve the officers’ salaries.

Neither candidate directly addressed the state’s shaky financial condition or repeated their campaign comments that they would consider tax increases. Feinstein did mention her support of Proposition 133, a measure that would increase the state sales tax by a half-cent to fund drug programs. But she did not directly say that the measure includes a tax increase.

One of the sharpest clashes of the debate came at the initial question, when both were asked how they would change California. Feinstein said the state’s problems were due to leaders who “pull over to the side of the road and let the world pass . . . by.” She turned that into a criticism of Wilson’s decision to stay in California to campaign, rather than take part in federal budget negotiations.

“Look what’s happening in Washington today,” she said. “The government has shut down. My opponent is here. He’s not where he should be, back there helping make a difference with the budget.”

In response, Wilson scored Feinstein for her handling of the fiscal situation in San Francisco when she was mayor: “I did not leave my city with a $172-million deficit. I did not raise taxes six times,” he said.

After the debate ended, Feinstein offered to suspend her campaign schedule, if Wilson asked, so that he could return to Washington without handing her the campaign advantage. She also said she felt “very good” about her debate performance.

Wilson had no immediate response to Feinstein’s offer, but he said in the debate that it was more important to remain in California for the campaign.

“I enjoyed it,” Wilson said after the debate--adding that he thought his opponent “lost on points.”

Sunday’s exercise was the first time Wilson has debated in a statewide general election since 1982, when he and then-Gov. Jerry Brown clashed in their battle for the Senate seat Wilson has held since then. Feinstein took part in two pre-primary debates with her Democratic opponent, Atty. Gen. John K. Van de Kamp.

Security outside the Burbank studios was tight as an estimated 100 demonstrators turned out before the debate to air their grievances over the candidates’ various positions and to express support for their favorite gubernatorial hopeful. More than two dozen television stations signed up to carry the debate statewide, giving it the potential to be the most-watched state gubernatorial debate ever. But it was up against a stiff challenge--competitor KCBS-TV began airing the second game of the American League baseball playoffs at 5 p.m., an hour before the debate began.

As negotiated by the candidates, the debate featured a split format. In the first half hour, the debate panelists asked a question of a candidate, who was allowed a two-minute response. The opponent was then given a two-minute rebuttal, followed by a one-minute cross-rebuttal by the first candidate.

The debate questioners, selected from a list acceptable to both campaigns, included KCBS-TV reporter Terry Anzur, KRON-TV reporter Rollin Post and Fresno Bee political reporter Jim Boren. The moderator was KNBC’s Jess Marlow.

The second half-hour was designed to be a verbal slugfest between the candidates, unimpeded by any referees. One candidate asked the other a one-minute question, to which a two-minute response was allowed. The questioner received two minutes to rebut the answer, which was followed by one minute for cross-rebuttal.

The candidates will meet in San Francisco on Oct. 18 for their second exchange. That debate is not expected to be aired statewide.

If tradition holds, voters will learn more about the candidates from news reports that circulate this week than by listening to the debate itself, particularly if one of the two candidates was seen to have made a gaffe. One-liners, mistakes and sharp comments tend to become the focus of news coverage, rather than the usually substantive debates themselves.

Contributing to this story were staff writers Douglas Shuit, George Skelton, Bill Stall and Tracy Wood.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.