STAGE : Five Guys Jive : ‘Five Guys Named Moe,’ a show inspired by Louis Jordan’s music, started in obscurity but is now headed for London’s West End

LONDON — Nomax, a ‘90s fellow in blue jeans and white T-shirt, sits hunched over in his chair, drinking and ruminating over a romance gone sour. Old R&B; spills out of his modern radio. The deejay reports it’s 4:45 a.m.

Flash, blam, puff of smoke from the radio, and suddenly five hipsters appear, all spruced in ‘40s finery. Nomax needs a lesson in the mysteries of life and love, they say, and they’re here to give it to him. They break into song as they introduce themselves. They’re five guys named Moe.

I wanna tell you a story from way back

Truck on down and dig me Jack

There’s Big Moe

Little Moe

Four-Eyed Moe

No Moe

Look at brother, look at brother,

Eat Moe.

Using that threadbare premise to unleash 20 song-and-dance numbers, the musical “Five Guys Named Moe” pays tribute to the ‘40s-era singer, saxophonist and bandleader Louis Jordan, whose clever lyrics and catchy melodies were far more influential than his low name recognition would suggest.

Jordan is never mentioned during the show. But the entire musical consists of songs he either wrote or popularized, with each number presented as another bit of street-corner philosophy for Nomax to ponder.

The show’s structure gives the Moes an almost biblical quality, like messengers imparting the wisdom of an unseen being. Five Guys Named Moses.

Nomax sometimes just stands around and looks puzzled as the Moes go through their brilliantly choreographed paces. Sometimes he joins in, becoming, in a sense, a sixth Moe (Slow Moe, perhaps).

Written by American actor Clarke Peters, the show was booked for a six-week run at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, a shabby but cozy theater in London’s impoverished East End. Longevity seemed unlikely.

But in classic show-biz fashion, “Five Guys” debuted amid the grand chorus of fringe theater groups clamoring for attention and came out a star.

For two weeks, small but enthusiastic audiences danced, participated in sing-alongs and joined a cast-led conga line that snaked into the bar at intermission. Drinking in the seats during the show--a usual Stratford East practice--and the swinging usherettes seemed like part of the show.

Feeling confident, the producers summoned the critics. The resulting reviews in Britain’s national newspapers were uniformly dripping with praise. There were lots of those short, punchy phrases that wind up in the ads. “One damned highlight after another,” said the Independent. “A joyous and walloping hit,” said the Guardian. One critic referred to the “first-night audience,” apparently unaware the show was already one-third through its run before he saw it. Tickets for the remaining four weeks immediately sold out.

Cameron Mackintosh, the world’s premiere producer of musicals (“Miss Saigon,” “Cats” “The Phantom of the Opera”), was among the pack of producers who flocked to the show after the stunning reviews appeared.

“I went for a night out with friends,” says Mackintosh. “I was captivated by it.” When the performance ended, “we looked at each other, I nodded my head and went to find the house manager to say I wanted to do it.”

Mackintosh bought the musical and will open it Friday in London’s West End theater district. “Five Guys” is the first show he has taken to the West End that he did not produce himself.

Louis Jordan was born in Brinkley, Ark., in 1908, to a bandleader father who taught him to play the clarinet and saxophone. After playing in other musicians’ bands for most of the ‘30s, Jordan formed his own New York-based combo in 1938, the Tympany Five, and became popular first in Harlem and then the rest of the country. His lively performances, innovative musicianship and funny lyrics heavily influenced the early rock ‘n’ rollers including Chuck Berry and Bill Haley. Although Jordan remained popular throughout the ‘40s and early ‘50s--”Choo Choo Ch’ Boogie” sold a million copies in 1946--he suffered a fate similar to other black pioneers in the music business and never received the credit and rewards due him. He moved to Los Angeles in the early ‘60s and died there in 1975.

It was five years ago that Peters began thinking about a show that would celebrate Jordan’s music.

The 38-year-old Peters was born in New York and moved to Europe in 1971, where he won a role in the Paris company of “Hair.” He has mostly lived in England since then, establishing a successful career on the British stage and in British television.

In 1985, Peters was making the long commute from London to Sheffield each day to perform in “Carmen Jones,” and while listening to Jordan recordings found himself trying to connect certain songs with staged scenes.

A line from “Five Guys Named Moe” kept coming back to him: “They came out of nowhere.”

Peters felt that if he could introduce five characters “out of nowhere,” he would have “license to put in almost anything that Louis had done.”

After finishing the evening’s performance in Sheffield one night, Peters had other cast members join him in staging a 14-minute version of “Five Guys.” He had the Moes coming out from under a bed.

“It worked,” Peters recalls. “People laughed.”

But Peters went onto other things and the Moes remained dormant. Then, last February, while Peters was appearing in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” at the National Theatre in London, he staged another after-hours version of “Five Guys,” this time for four nights. It was longer and featured the Moes popping out of the radio.

Among the few people who saw that performance was Philip Hedley, artistic director of the Stratford East, who arranged to finance and stage a full musical.

Hedley, who is leading a campaign for subsidized theater, is known for taking on new works. “Subsidy gives you the right to fail,” says Hedley, who is adamant that fringe and experimental theater should not exist as research and development labs for the West End. But he is proud that “every now and then something comes out like ‘Five Guys Named Moe.’ ”

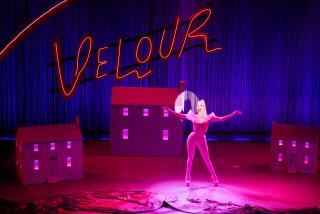

A creative team was assembled, the structure of the show was revamped, the selection of songs was overhauled and the six-man cast was brought together. The stage was left sparse, with a few cartoonish skyscrapers across the rear and a five-piece combo in a back corner. Props would be few: a table, some chairs, a radio and a chicken headdress for Four-Eyed Moe, who sings “There Ain’t Nobody Here but Us Chickens.”

The show was penciled in for a six-week run. Ticket sales were slow at first, but as Peters remembers, “We opened up to the best time these people ever had. You just knew there was something extraordinary happening.”

Mackintosh offered terms that were extremely generous to the Stratford East, says Hedley. The producer is giving the fringe theater nearly $100,000 up front and then 1% of the gross for the West End run and half the profits. Generally with fringe shows transferring to the West End, the originating theaters receive 2% of the gross and none of the profits.

“It was an amazing offer from Cameron,” says Hedley. “There were no negotiations. He just stated the terms.”

The question now, of course, is whether the fringe hit can succeed in its shiny new surroundings.

“The challenge is the reserve of the West End audiences,” says writer Peters, who plays Four-Eyed Moe.

But Mackintosh hopes to maintain the zest of the original production by re-creating the atmosphere of the East End theater experience as much as possible.

“My job,” says the producer, “is to try to re-create exactly those ingredients in a slightly more elegant space.”

The first step was pricing. Although the cost of most seats for “Five Guys” at the Lyric reflect its new upscale location, tickets for the gallery continue to sell for 3 ($5.85) as they did at the Stratford East. That theater draws much of its audience from the surrounding, predominantly black, neighborhoods, which are among Britain’s poorest. The pricing strategy gives “Five Guys” the least expensive ticket in the West End.

Advance sales figures reveal that East Enders are responding, says Mackintosh, who wants to make the musical accessible to people who usually cannot afford London’s top shows.

Among other steps Mackintosh is taking to maintain the show’s ambience is the policy of permitting drinking during the performance. The Lyric will become the only major theater with cocktails and pints in the stalls (orchestra seats) and circles (balcony).

Mackintosh realizes the West End run will have to create some of its own charisma, however. “You can’t really pretend you’ve driven for a half hour to the East End when you’re a few minutes walk from Piccadilly Circus,” he says.

Mackintosh says there already has been interest in moving the show to Broadway.

Well-established in Britain, Peters has had little interest in returning to the states. But as he contemplates going to Broadway, he grins broadly and leans back in his chair, like a self-made millionaire envisioning his next high school reunion.

“I would go back there in a second like this,” he says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.