COLUMN ONE : Schools Reach Out to Blacks : Efforts are under way to reverse the discouraging educational track record of many black males. Role models have been helpful. One experiment inspires both hope and fury.

Every morning as she arrived at Matthew A. Henson Elementary School in a bleak west Baltimore neighborhood, Principal Leah Hasty saw “nothing but poverty behavior” in the young black men dealing drugs or drinking on the street corners.

She wanted a better future for her students, virtually all of whom are black and poor; many live in single-parent households headed by their mothers or grandmothers. So last year, Hasty started a second-grade class made up of 26 boys, assigned a dedicated black man to teach and nurture them, and, with no special curriculum and no extra money, has begun to get results.

In several areas--including New Orleans, Chicago, Maryland’s Prince George’s County and Los Angeles County--efforts are under way to improve the discouraging educational track record of many of America’s black males. Mentoring programs--in which successful black men provide role models, encouragement and one-on-one help for disadvantaged students--are emerging as the most widely used approach. But the boldest initiative to date, which goes much further than Baltimore’s, has sprung from Milwaukee, where a divided school board drew nationwide attention--and controversy--by deciding to set up two schools this fall designed specifically for black boys.

“During the past five years, there has been increasing interest and attention to the underachievement of black male students. It’s gotten to the point in the last year where everyone is paying attention,” said Jomills H. Braddock II, director of the Center for Research on Effective Schooling for Disadvantaged Students, based at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“It’s happened in part because trends in underachievement in school among African-American males have been so startling and going in the wrong directions,” Braddock said.

The heightened attention has drawn criticism from some educators and others who say it reinforces harmful stereotypes while ignoring the fact that many young African-American males, including some suffering the effects of severe poverty, do very well in school and grow up to make positive contributions to society. Critics are especially concerned that setting up schools for black males will isolate them and reverse more than four decades of struggles to desegregate the nation’s public schools.

But even the critics agree the statistics are disheartening.

According to several recent studies, disproportionate numbers of black male students are assigned to special education classes or are singled out for discipline, or drop out of school altogether. Of those who do graduate, one out of three has a grade point average below C. At its national convention in Los Angeles last summer, the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, alarmed by sobering statistics showing high unemployment, incarceration and homicide rates among young men, held a special session on “The Endangered Black Male.”

“We as educators clearly have failed, not only with a lot of kids at risk but even more so with black male kids,” said Larry Springer, project administrator of the Los Angeles County Office of Education’s newly created Male Black Students Task Force.

The county’s task force, charged with developing more effective educational strategies to share with the 82 districts in the county, is one of a handful of similar efforts in California. The San Diego Unified School District, for example, has begun an experimental African-American Pupil Advocate Program that teams trouble-prone youths with a black advocate to act as mentor and role model. In 1989, the state Department of Education and the California State University system agreed to establish a center at San Francisco State to examine the educational failure plaguing many black youngsters.

Some of the efforts undertaken elsewhere include:

* New Orleans, where a committee headed by Antoine M. Garibaldi, a dean of Xavier University of Louisiana, conducted an exhaustive study of problems experienced by black males in the public school system there. It made more than 50 recommendations, including better teacher training and courses to help white staff members understand racism and its negative effects, more encouragement and higher expectations for black youngsters and improved school-parent relationships.

* Chicago, where several public schools are setting up “Afro-centric” curriculums, in which African culture is infused in a full spectrum of academic subjects. And a school on the city’s west side plans special weekly classes to build boys’ self-esteem, instill a knowledge of African history and provide positive role models.

* Prince George’s County, Md., in the Washington metropolitan area, where a broad-based community group held hours of public hearings before embarking this year on several programs designed to boost the academic achievement of the predominantly black, middle-class district’s male students. With about $2 million in start-up funds, the district expanded its curriculum to include more black history and culture, required more sixth-graders to take pre-algebra classes, upgraded teachers’ skills and began a student mentoring program with business, professional and community groups.

Unlike the Milwaukee and Chicago programs, however, the Maryland district’s focus is on changing the whole system, not setting up separate schools or projects. “Here we fundamentally believe that it’s the mainstream system that has to change. Eventually, a separate program would be overwhelmed,” said Warren Simmons, the administrator charged with ensuring equitable treatment for all groups of students.

The various approaches reflect the heightening debate over how to proceed and even whether it is appropriate to single out black males when the education system has failed with many other groups as well.

“In many areas, children of color and poor children are not being properly educated, but it is in vogue now to talk about black males,” said Shirley Thornton, a deputy superintendent of public instruction for California.

“What bothers me as an African-American educator is that we have been put into a pathological ethos; society says that there is something wrong with us, that we need fixing. When do we start trying to see what’s wrong with whole (education) system . . . and when does our society begin to value all children?”

Thornton and others believe the best approach lies not in creating separate schools or policies but in making wider, more effective use of the many proven techniques that have succeeded with various groups of students who seemed headed for failure. They cite the longtime work of such successful innovators as Yale psychiatrist James P. Comer, who built a strong family-school relationship into his system of reaching inner-city youngsters; principals Lottie Taylor in New York and Madeline Cartwright in Philadelphia, who made marked improvements in their troubled urban schools by encouraging parental involvement and setting high standards of conduct and achievement, and Chicago teacher Marva Collins, who got widely publicized results with disadvantaged children by combining lots of individual attention and praise with strict academic demands.

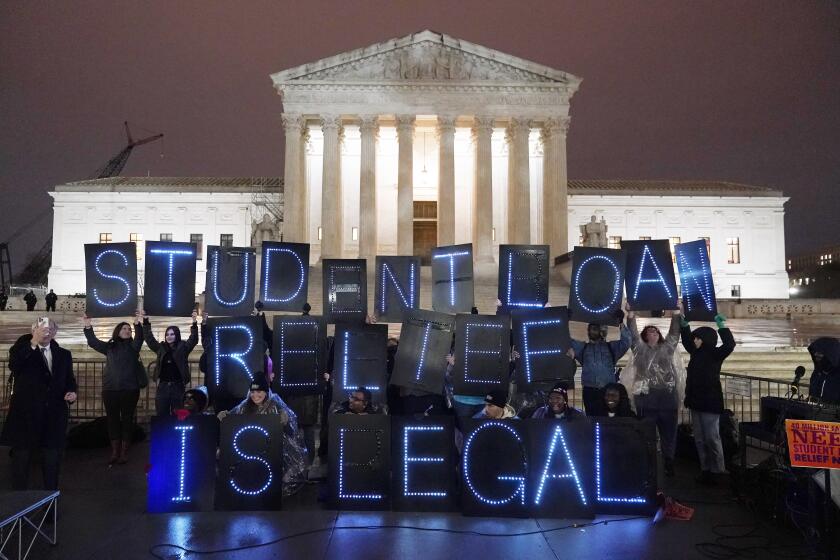

Nothing has escalated the debate more quickly than Milwaukee’s plan to open its “African-American Male Immersion Schools,” one for elementary students and another for middle school youngsters. The plan represents a radical departure from black Americans’ nearly half-century-old tradition of pursuing integrated schools, and has split the black community, educators and civil rights activists.

What is happening in Milwaukee illustrates the frustration of a number of black parents who, fed up with the failure of public schools to educate their children, are extolling separate schools tailored to their specific needs and steeped in Afro-centric culture, history and values.

The boys’ schools project comes on the heels of a controversial school voucher program that allows a limited number of low-income Milwaukee students to attend existing private schools at public expense. The program, which began in September, was ruled unconstitutional last month, but the voucher program continues while the ruling is being appealed.

And the voucher program was preceded in 1987 by a failed attempt by blacks to carve their own all-black school system from the Milwaukee school district.

Kenneth Holt, a black middle school principal who is overseeing the establishment of the black male immersion schools, said they result from the realization that current ways “are not meeting our kids’ needs. . . . We’re miseducating large numbers of African-American students and other students of color.”

Between 1978 and 1985 94.4% of all students expelled from Milwaukee public schools were black, according to a report last spring.

The report also said that 80% of black male high school students have grade averages lower than C; and in the 1989-90 school year, blacks, who make up slightly more than one-fourth of the system’s 93,000 students, accounted for half of the school suspensions.

The black male schools were approved 5 to 3 last fall, and, though no blacks on the school board voted against the plan, it drew immediate opposition from the local NAACP and from some educators.

“My flat-out response is that I’m against all segregation--I don’t care what kind it is,” Milwaukee NAACP President Felmers Chaney said.

Doris Stacy, a white, self-described liberal/progressive swho has been on the school board 18 years, said she believes the plan will run into legal problems, will be ineffective and will drain dollars from proven programs. Furthermore, she suspects that the plan appeals to those whites who have resisted integration.

“The message to the black child is, ‘We are going to isolate you,’ even though we have strong evidence that the black students in our integrated schools do better (than those in the district’s all-black schools),” Stacy said.

But proponents of the plan note that 17 schools are all black, including one high school, the result of a settlement of a lawsuit that left only some of the district’s schools integrated, Holt said. Because the new schools will operate on campuses that already are predominantly black, the project is not creating segregation, he added.

Gretchen Miller, legal director of the Milwaukee chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, has questioned the constitutionality of the program on grounds that it might violate the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling outlawing “separate but equal “ schools. She also was concerned about gender discrimination.

The district has made changes that removed what she called “the most blatant constitutional questions.” These include opening the applications to girls and to members of other races and the possible hiring of white teachers.

The organization has so far been unable to decide on a formal position.

Holt said many decisions--including selection of students and faculty, budget and even school sites, the length of the school day and whether students will be required to attend Saturday classes--still have not been made.

Some features are clear, however. Students, divided roughly evenly between the “home” schools and applicants from throughout the city, will be chosen by lottery, wear uniforms and get strong doses of African history and culture during extended school hours. Parents must sign contracts obligating them to visit the school regularly and otherwise be involved, and a mentoring/male role model component will be included, Holt said.

The Milwaukee project has stirred divisions of opinion, especially among black educators.

Psychologist Thomas A. Parham of UC Irvine, who has written and lectured extensively about the plight of black males in America, said he is “personally and professionally excited about” Milwaukee’s plan because of many of its features and because of the commitment it represents.

But Charles V. Willie, professor of education and urban studies at Harvard, calls the project “a short-term convenience that could be a long-term disaster” because of racial isolation and the implicit message that a particular group of students “are not good enough” to function in an integrated setting.

What most do agree on, however, is the efficacy of good mentoring programs, a feature of virtually all efforts to help black male students. Of the scores that have sprung up nationwide in recent years, one of the better known is Project 2000, founded by Spencer Holland--now director of the newly formed Center for Educating African-American Males at Bowie State University in Maryland--while he was a school administrator in Washington, D.C. Matching black professionals with male students for intensive tutoring and social support, it has been adopted by schools in Miami and other cities.

In Los Angeles, a group called 100 Black Men works with 1,700 youths in grades 8 through 12, providing academic encouragement and college scholarships. Dr. Bill Hayling, who founded the local chapter when he moved here from New Jersey in 1981, said the group is planning a new program to reach younger children, particularly those living in public housing projects. “We’re a cross-section of successful black men who all felt we wanted to give something back to our community,” said Hayling, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center and 100 Black Men’s national president.

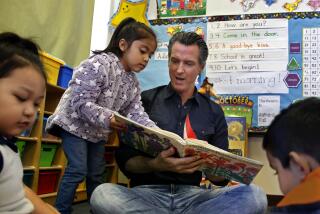

A mentoring program, staffed by volunteers from a black fraternity, has become a key part of the all-boy third-grade class at Baltimore’s Henson Elementary. So have the efforts of teacher Richard Boynton, 36, who spends lots of extra time with his students, including playing basketball with them on Saturday mornings and taking them on outings to libraries and museums as rewards for good performance.

Except for the fact that the class is made up only of boys and taught by a man who has stayed with the group for two years, the class is no different from other third grades at Henson and throughout Baltimore, Hasty said. She expects to send the boys back into classes with girls--perhaps at the start of the next school year--once she feels the advantages they are gaining in Boynton’s room are strong enough to make some lasting differences in their success.

Already, the signs are encouraging. Attendance has improved markedly, discipline problems have virtually vanished and the rate of academic accomplishment has increased for all the boys; more than half of them have exceeded the expected achievement gains. Hasty, a 34-year veteran of the public schools, thinks it helps not to have to compete with girls. “Little girls at that age just seem to move faster,” she says.

But she believes the biggest factor is the boost in self-esteem and the positive role models the youngsters find in Boynton and his group of volunteers.

“These children needed to see there are men in this world who are not here dealing (drugs) on the street corners, who are not drunk at night, who take care of their families,” Hasty said, “men who provide games for them, take them places, support their dreams. And talk about their futures.”

Merl reported from Los Angeles, Harrison from Milwaukee.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.