Giant Bibliography Will Be One for the History Books : UC Riverside: Computer catalogue will list all early English publications from 1475.

RIVERSIDE — It’s a bit like sorting the grains of sand on a beach or documenting the blades of grass in a wind-swept meadow, an endeavor so daunting that most would simply throw up their hands and declare it futile.

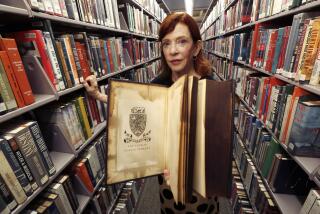

But historian Henry Snyder is a determined sort, a man not easily overwhelmed. And so, in a warren of offices in the bowels of a nondescript building on the UC Riverside campus, Snyder and several loyal assistants have tackled a monumental task:

By 1995, the team hopes to complete a gigantic computer bibliography, cataloguing everything published in English from the birth of printing in Great Britain in 1475 through the end of the 18th Century.

In a joint project with the British Library in London, the Riverside scholars have scoured the globe for books, political pamphlets and all the other odds and ends that trickled off the hand-turned printing presses of the period.

The effort, which began in 1977, is far more than a laborious listing of books. Employing the ingenuity of detectives, the dogged cataloguers have uncovered caches of heretofore unknown rare volumes in places as varied as the Wichita Public Library in Kansas and ancient diocesan libraries in the countryside of Ireland.

Each day, new works from the bygone era turn up and are added to a mushrooming database. By mid-decade, Snyder predicts the repository will contain half a million separate titles--a list retrievable in seconds through the punch of a few keys on a personal computer.

Why undertake such an exhaustive effort? For starters, the $20-million project--the most ambitious of its kind ever attempted--will be a veritable godsend for scholars.

By revealing the existence of previously unknown works, it greatly expands the resources available to historians, economists, scientists and students of any other imaginable field.

“They have put on record material that has not been available before, and the effect of that in terms of advancing scholarship will be tremendous,” said Paul Alkon, a professor of English literature at USC.

The computer catalogue also provides substantial time-saving benefits. It not only lists the title of a given volume, but reveals the number of known copies and where they can be found. That means a researcher no longer has to waste time and money combing the world’s libraries in hopes of locating a certain book.

“In the past, I would consult a printed bibliography and then simply travel to libraries I thought were likely to have the works I was seeking,” said David Vander Meulen, an expert on 18th-Century English poet Alexander Pope and a professor at the University of Virginia. “Now, with a few strokes of the (computer) keys, I can pinpoint exactly what I’m looking for.”

The sophisticated searching capabilities of the computer program are another remarkable attribute, allowing retrieval of an entry by author, title, subject and a variety of other ways. Sometimes, users make surprising discoveries.

“I was tinkering around one day and I came across the words rock salt in a title,” Vander Meulen recalled. “Out of curiosity, I did a search to see how many times the term appeared in the 18th Century. Lo and behold, I found eight pamphlets written in 1700 and discovered what I call the Great Rock Salt Controversy of 1700, a dispute over import taxes of some sort. . . . It proves that the use of this catalogue is limited only by one’s own creativity.”

Although the bibliography may seem arcane and of little use to the average person, Snyder insists that such a perception shortchanges the project’s value. Indeed, the professor believes it opens “a new window on the past” that “anyone interested in our heritage” and the “roots of today’s culture” would want to peek through.

“There is something for everyone here, and it covers the whole history of our culture,” said Snyder, 61, an energetic, silver-haired man whose passion for his work tumbles forth in rapid-fire sentences. The eclectic assortment of works in the bibliography--only periodicals, maps, printing labels and music have been excluded--supply a richly detailed portrait of life in the past.

Entries in the catalogue range from the weighty--such as editions of the Bible and acts of Parliament--to the whimsical and downright ordinary. A large percentage of the titles exist only in a single copy, and among the most intriguing are the numerous “broadsides”--one-page notices that were common in the era.

Many are political commentaries and exhortations, anonymously published because of the stiff penalties for seditious libel imposed by the government at the time. Others include a 1794 bulletin detailing the attributes of “a remarkable famous pig” from Middlesex; a 1787 book listing the revised rules for the game of cricket; a 1782 notice warning the people of Newcastle-upon-Tyne to be on the lookout for pickpockets; and even a 1788 “man of pleasure’s calendar” listing the accomplishments of 75 prostitutes in a central London district.

“A large part of the fun in this job is uncovering treasures like these,” Snyder said as he shuffled through some of his favorite entries. “This material, particularly the broadsheets, is so elusive, and much of it we never knew existed. We’re pulling it all together now so it can be of use.”

The bibliographic project launched at the British Library initially sought only to log the works printed in English during the 18th Century--a sizable task in itself. Last year, UC Riverside founded a Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, and Snyder, the center’s director, resolved to expand the computer catalogue back to 1475, the year William Caxton introduced the art of printing from movable type to England.

Gathering and logging the bibliographical entries has been a painstaking process. In the beginning, the scholars mailed requests to hundreds of libraries throughout the world, seeking lists of their collections of pre-19th Century English works.

The response was overwhelming: More than 1 million slips of paper--representing the libraries’ holdings--have so far been sent back, and a squadron of hired students continually sorts them alphabetically into cardboard boxes before they are logged into the computer file by cataloguers.

In some cases, the bibliographers send a team to personally search libraries, copying down each title relative to the project. At the William Andrews Clark Library in Los Angeles, for example, a volunteer recruited by Snyder spent nearly two years recording 15,000 titles.

Another team documented 100,000 titles at the various college libraries at Oxford University, and two doctoral students spent 18 months rummaging through the faded 18th-Century files in England’s Public Record Office--the equivalent of our National Archives. Their haul? More than 15,000 individual items, most of them unusual ephemera found nowhere else.

Snyder himself has done a good bit of prowling. He has toured libraries in Eastern Europe and recently came across a rare collection of works in a crumbling old diocesan library at Armagh in Northern Ireland.

“You can’t believe the stuff that is lurking in the nooks and crannies,” Snyder said. “It is hiding in people’s attics, in the libraries of the nobility’s great country estates, everywhere. Little by little, we’re finding it.”

Funding for the bibliography project has come from the British Library, the National Endowment for the Humanities and numerous private foundations.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.