A Silent Night : Deaf Contestant in Miss Anaheim Scholarship Pageant Wonders If She Really Had a Fair Chance

What we have here, perhaps, is a failure to communicate.

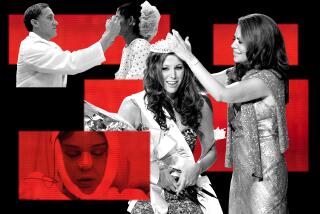

That’s the positive spin on Lynn Lochrie’s adventure that wrapped up the other night, with lots of glitter and radiant smiles, on a stage erected at an Anaheim hotel.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. April 11, 1991 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday April 11, 1991 Home Edition View Part E Page 9 Column 1 View Desk 1 inches; 32 words Type of Material: Correction

‘Silent Night’--Because of computer hardware problems, Dianne Klein’s byline was misspelled and several typographical errors appeared in her story in some copies of Monday’s View. The story was about a deaf beauty contestant.

But there are less charitable ways of looking at it, too.

Lynn Lochrie is a 24-year-old landscape designer whom a variety show host might introduce as “the beautiful and the talented.” And she seems as if she would be comfortable with that label.

She is vivacious, thoughtful, determined and self-confident. She stands up for herself, with a smile. She has many friends in both of her worlds: the hearing and the deaf.

It is the hearing world in which this story unfolds.

Lochrie was one of 14 women competing at the Miss Anaheim Scholarship Pageant, vying for a $1,000 scholarship, prestige and a crown. The winner goes on to the Miss California Pageant in San Diego this June, and the winner there will compete in Atlantic City in September for the mantle of Miss America 1991.

Lochrie, however, did not finish in the top four, and the contestants were not ranked below that.

But she wonders whether she was really given a fair chance.

Lochrie, 24, was born deaf. She hears not a single sound. When she dances, she counts silently to herself. When she communicates, she reads lips and talks with her voice and her hands.

Except sometimes her message doesn’t get through.

A former Miss Deaf California, Lochrie asked the pageant for an interpreter to help her decipher the judges’ spoken questions during the interview portion of the contest, which counts for 30% of the final score.

The request was denied.

“I just didn’t feel she needed one,” says Earline Jones, the Anaheim pageant’s executive director. “Why should she have someone up there with her? She did fine. . . . There can only be one queen. There were four girls who made it and 10 that didn’t.”

And Bob Arnhym, who as president of the Miss California pageant oversees the local contests, adds this:

“There is a policy of the Miss America pageant--and it has been in place for quite a number of years--that a contestant may not compete if she is assisted by anyone.

“It was originally designed because of talent, things like back-up singers or spotters for a gymnast . . . and the intent at this moment in time is that all contestants must be on an equal footing. Many, many young deaf women have competed (in the state), and they have not had an interpreter.”

Only one of them, from Tulare County, has won a title. Deidre Hamilton went on to compete in the 1984 Miss California pageant, where she was a runner-up.

Lochrie was reluctant to make much of a fuss when Jones told her that she couldn’t have any help. She says the director’s denial was so adamant that she knew she couldn’t make her budge.

And Lochrie wanted very much to compete. She agreed to talk about the pageant only after the judges’ votes had been cast.

Another deaf beauty pageant contestant, Julie Rems, caused a stir last month when the director of the Miss Culver City Scholarship Pageant suggested that she not use an interpreter, even though she had used one in the same contest the year before.

Rems, who placed second last year, was angry and threatened to quit. The pageant director eventually allowed her to use an interpreter. Rems competed but did not place in the top four.

Rems, also a former Miss Deaf California, was at the Anaheim pageant to cheer Lochrie on. She is still incensed over what happened in Culver City--Arnhym and Rems had a heated discussion on “The Home Show” the day of the Anaheim pageant--and suggests that she may sue. She doesn’t like anybody putting limits on what she, as a deaf person, can do.

Lochrie says she believes that the pageant officials just don’t understand what using an interpreter really means.

It is not, she says, a way to cheat.

“Reading lips is an art,” Lochrie says. “It can take a while to get used to how somebody speaks. It’s like a fingerprint. Everybody is different.”

During the competition, Lochrie says she did not understand three of the questions that the judges asked. And some of the judges appeared to have had trouble understanding her too.

“We are not zeroing in on the deaf,” says pageant president Arnhym. “They are zeroing in on us . . . . I’m not suggesting our policy will change. Imagine having to compete on an equal footing with hearing girls and then winning. What a triumph! And what a shallow victory it would be to gain an advantage in the judging because she was deaf.

“This may be a trite analogy,” Arnhym goes on. “But there’s a program called the Special Olympics designed for those who wouldn’t be competitive in the regular Olympics without changing the rules. . . .

“I’m 5-11 and I like basketball, but if I want to compete in basketball, I can’t ask them to lower the net. That is a fact of life. I chose other sports. I didn’t feel discriminated against because I wasn’t tall enough.”

Nor, says Arnhym, should deaf women feel discriminated against within the Miss America pageants. They are welcome here.

So long as they abide by the pageant’s rudes.

Lochrie, who has planned to enroll in a master’s program in architecture at UC Irvine this fall, hopes the rule against interpreters will change soon. She says she will compete in the Anaheim pageant next year if her request for an interpreter is approved.

“I want to educate the public about hearing-impaired people,” she says, “and change the rules. I want people to understand. I want deaf girls to be able to compete on an equal footing. This kind of thing has been happening to me my whole life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.