U.S. Jobless Figures Fail to Add ‘Hidden Unemployed’ : Work: Part-timers seeking full-time status and those who have given up job hunt total about 7.1 million.

- Share via

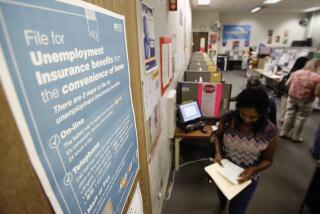

When the federal government released the March unemployment figures last Friday, people like Mary Diggins and Jorge Gonzales were not counted.

Some economists--primarily those who paint the harshest portrait of the economy to justify stronger government intervention--think they should be.

Diggins, a supermarket cashier, is one of 6.1 million working people who want full-time work but can’t find it, and are forced instead to work part time, a decision which not only means a smaller paycheck but often inferior employer-paid benefits like health insurance.

Gonzales--a pseudonym to hide his embarrassment--is one of nearly 1 million unemployed people who want to work but have become so frustrated that they quit actively looking. The Labor Department classifies them as “discouraged” workers and does not count them when it tabulates the monthly unemployment rate.

Together, these two classes of people, sometimes referred to as the “hidden unemployed,” approach in number the 8.5 million individuals who made up the official 6.8% unemployment rate in March.

“What you really have is a total unemployment and underemployment rate of 12.4%,” said Lawrence Mishel, research director of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal Washington think tank.

The numbers of involuntary part-time workers and discouraged workers have been sharply rising as the national economic recession takes hold.

The Labor Department estimates that the number of involuntary part-timers like Diggins rose by 500,000 in February alone, a jump of 10%, as many companies either cut employees’ hours or laid them off, forcing them to scramble for new, part-time positions. February was the first time since the 1982-83 recession that the number had climbed to 6 million. The total increased by another 100,000 in March.

The number of discouraged workers reached 997,000 in the first quarter of 1991, a 27% increase from the first quarter of 1990. It was the highest number since the first quarter of 1988.

Diggins, 42, of Hawthorne, still remembers vividly the day in 1987 when she lost her full-time status.

She had been working as a cashier for more than 10 years for Safeway, which was then being merged into the larger Vons chain. That summer, she said, her store manager informed her that her full-time job was being given to a newly arrived cashier with more seniority. Diggins, then a single mother of two teen-agers and an infant, was being reclassified as a part-timer.

“My work week went from 40 hours to between 16 and 18 hours a week,” she said. “I just couldn’t believe it. It was a total shock to me. I was so stressed I went to a doctor.”

The supermarket industry, under competitive pressure to offer wider hours of operation to customers, is an example of how many sectors of the economy have aggressively eliminated full-time jobs in favor of part-time ones in an effort to cut labor costs and respond more quickly to shifts in business.

In the nation’s retail and wholesale businesses, nearly a third of all workers are employed part-time. Diggins’ union, the United Food and Commercial Workers, estimates that two-thirds of the supermarket workers it represents are part-timers.

About 21 million people--17% of the U.S. labor force--work part time. Involuntary part-timers account for 29% of this part-time work force, the Labor Department says. The number of involuntary part-timers has risen 75% in the last 15 years, and accounted for more than 40% of the growth of part-time labor in the 1980s. Critics of U.S. economic policy say that much of the job growth in the last decade was due to this increase in low-wage “contingent labor.”

Diggins said she survived the shift to part-time work by moving in with her mother. It took her a year before she could scrape together enough money to rent her own apartment again. She said she did it by pestering her store manager and managers at other Vons stores for more hours each week, a practice she continues.

Her persistence now allows her to work 20 to 28 hours a week. While she is well-paid at $13.25 an hour, she said she has never recovered the economic stability she once enjoyed. She has surrendered a hard-won middle-class life and returned to some lower-middle-class hardships reminiscent of her childhood in a family of 13 children.

“When I was full time, I had two months rent saved in case something happened. I could pay my bills without having to juggle them around. Now I live paycheck to paycheck,” she said. “Right now I can’t pay my rent Monday if I don’t get my check on Friday. I almost got my car repossessed. If it has anything to do with spending money, like amusement parks, we don’t go.”

The case of Jorge Gonzales, and the statistical category he represents, is murkier but more painful.

In the course of an hour of conversation inside a Bell Gardens doughnut shop, Gonzales, 35, weaves in and out of being what the government considers a “discouraged” worker. Yes, he wants to work. But he’s not reading newspaper want ads each day and lining up interviews. Yes, he has signed up with a government job-training program. But he’s no longer hopeful.

He is a tall, hulking man who has gained 100 pounds and lost most of his confidence in the last three years due to inactivity. He grew up in a tough East Los Angeles neighborhood, got married and began having kids--five of them now. For a high school dropout, he had a good job--$9.77 an hour after eight years of working in the shipping and receiving department of a linen supply company. It was enough so that he and his wife, who also worked, could take the kids to Disneyland a couple times a year.

Then, in 1988, he injured his shoulder and couldn’t work. Recovery was slow.

The state’s worker compensation program paid for six months of retraining at a job that required less strength. Gonzales chose office machine repair. Over several months, beginning late last year, he went on 40 job interviews, he said, but none of them panned out. His monthly worker compensation pay ran out. He didn’t qualify for state unemployment insurance because he had been unemployed since 1988. His wife didn’t think he was looking hard enough for a job. They fought. In December he moved out.

But he didn’t have a place to go. So he moved into his van and slept in it--in the driveway of his rented home. He uses the house in the daytime, but not at night. It confuses his children and it confuses him. He’s doing the right thing, he tells them--he’s no longer a provider, he doesn’t deserve to live there. They cry. Funny, he says, he didn’t cry when a gang member shot him in the face by mistake when he was a teen-ager, robbing him of sight in one eye--but he cries now.

He can fix cars, so he does free-lance brake repair for friends. Most of them don’t have money so they pay him in other ways. One gave him a case of toilet paper. He took it to his kids.

And here’s what scares him about living like this: He’s getting used to it. He’s beginning to fit that impersonal Labor Department profile. He’s wrapped in an emotional spiral that has him doubting that he’ll ever find work again. He wants a job, but he’s nearly forgotten how to try.

“If I got a job, I believe I can get back together with my wife. But every day it seems like it’s getting easier to stay in the van. Stealing, that never crossed my mind, but now I’m thinking about it. It’s harder to look for work. I don’t like the way I look, living like this. Against someone who’s clean-cut, I can’t compete. I’m doubting myself more. I was never like that. I found that in job interviews I was talking like a little baby. I hate myself for that. I don’t feel like a man no more.”

HIDDEN UNEMPLOYMENT

Two measures of economic hart times--the number of people nationwide who have stopped looking for work out of discouragement, and the number who want full-time work but have to settle for working parttime-mirror the increase in the jobless population.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.