Singing Stone : Interest Centers on Ringing Rock Used by Prehistoric Indians

- Share via

MENIFEE VALLEY, Calif. — When Catherine Saubel, a 70-year-old Cahuilla Indian, stood before the 2-foot by 3-foot granite rock, she became emotionally overwhelmed.

“I was awe-struck just being in its presence. I visualized what it must have been like when prehistoric medicine men played ancient songs on the rock before large gatherings of people. This rock is very sacred to Indians,” Saubel said.

Curator of the Malki Museum on the Morongo Reservation near Banning for the last 26 years, Saubel has known about so-called “ringing rocks” all her life. But this was the first time she had ever seen one--or heard one.

When struck gently with a small rock, the granite boulder chimes like a bell. When struck in several places or with various-sized small rocks, different tones are heard.

During prehistoric times, scholars believe, ringing rocks were the central focus of elaborate cultural ceremonies. Today, officials in Riverside County, where the rock is located, hope to use it as the centerpiece of a park or American Indian cultural center.

“This sacred rock is a cultural treasure. It must be preserved not just for Indians but for everyone,” Saubel said. “It has to be protected with a fence or whatever it takes to prevent it from being damaged or destroyed by vandals.”

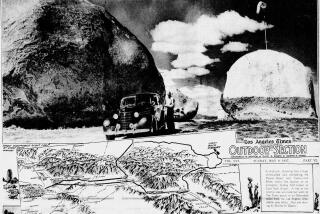

The rock is in Riverside County’s rapidly developing Menifee Valley, about 75 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles. Its exact location is not being publicized yet, for fear of theft or vandalism.

Ken Hedges, 47, chief curator at San Diego’s Museum of Man, said he knows of only seven such rocks in existence--all in the Southwest. But he said there may be similar rocks in other areas.

Diana Seider, 35, an anthropologist and the Riverside County Parks Department historian, described the melodious boulder as “an extremely rare natural phenomenon.”

Seider said archeologists have known of the rock’s existence for many years.

Efforts to protect it were launched last year as housing development began edging closer to the site. In November, Riverside County purchased the surrounding 20-acre parcel, Seider said.

“The big problem now is how to protect the rock,” said Seider, who also spoke of hopes for a park or cultural center.

“At some point in the future it would be great if a Native American individual or family could live on the site to guard the rock and to interpret it to visitors who came to the park to see and hear the rock’s amazing sound when struck,” she said.

Hedges mentioned the ringing rock of Menifee Valley in a scientific paper published late last year on the profusion of petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings) in the area.

“The rock’s special sonorous characteristics are believed caused by the way it is positioned and balanced on a giant boulder. There is considerable air space beneath the ringing rock,” he said.

Hedges said little has been written about ringing rocks in scientific literature. “Present-day Indians in the few places these rocks have been found are aware they were important cultural items in prehistoric time but other than that (they) really don’t know much about them,” he said.

Archeologist Constance DuBois of UC Berkeley described ringing rocks in a 1908 scientific paper, Hedges said. “She mentions they were used in Indian ceremonials when one man sang to the accompaniment of the rock while others danced.”

Research indicates that during prehistoric times, the ringing rock of Menifee Valley was part of a small community--a main village surrounded by six satellite villages, Seider said.

Clusters of granite boulders--the last remnants of the villages--are covered with prehistoric rock art primarily of geometric designs, she said.

The Menifee Valley rock contains a large deep circular indentation embraced by six smaller circular indentations.

Hedges said such cupules (or cup-shaped indentations) are on three of the ringing rocks that he has seen--one in the Colorado Desert in Imperial County, one near Virginia City, Nev., and another in Southern Arizona.

“What the indentations mean is one of the many mysteries relating to the importance of these strange rocks in the culture of prehistoric man,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.