Looks Could Kill as Face-Lift Patient Gets a Gun : Plastic surgery: Suburban Seattle woman shoots her surgeon and herself after complaining of constant pain. The doctor’s staff says her problems were psychological, not physical.

- Share via

BELLEVUE, Wash. — The story of Beryl Challis begins simply enough: A 60-year-old woman, her beauty fading beneath sags and wrinkles, hopes to turn back the years with plastic surgery.

A face lift, that’s all.

Like tuning a car, she told her husband. Like going to the dentist, she said. More than 50,000 Americans a year get face lifts, and the vast majority emerge happily with streamlined looks and bolstered egos.

But not Beryl Challis. Surgery left her tortured by pain, horrified at her new face and infuriated at the man she blamed for her misery.

After a year of suffering, she confronted her plastic surgeon at his office, pulled out a revolver and shot him to death. Then she drove home and fired one final bullet into her own head.

The murder-suicide raised a knot of questions: Was Beryl Challis what her family says, an average housewife distraught with pain from a botched operation? Or was she what the doctor’s staff suggests, a wounded soul with scars too deep for cosmetic surgery to reach?

The two who knew best are gone, leaving others to speculate on how one woman’s attempt to regain her beauty came to such an ugly end.

“I always knew my wife was a very vain woman,” said Albert Challis, 64. “She was a good-looking woman, and if you’re good-looking, you usually know it.”

Four days after the April 15 shootings, he sat in his darkened living room and stared at two snapshots on the table.

One showed Beryl Challis at 25: pretty, shapely, her wavy brown hair framing a face lit up by a pixie smile and mischievous eyes. In the other photo, taken shortly before her face lift, traces of her youthful beauty remained, but her skin had loosened, her smile had tightened, and her eyes seemed sadder, as if pining for happier days long gone.

The couple came to the Northwest in 1952, finding the wet, cool climate similar to their native England. Albert Challis worked as an auto mechanic, eventually running his own shop before retiring a few years ago.

Beryl Challis stayed home, rearing sons Christopher and Adam, now 32 and 25. She liked to sew, saving needed dollars by making her own drapes and sofa cushions. She was, her husband says, an ordinary housewife in an ordinary suburb.

But as the years went by, Bellevue turned less ordinary. The Seattle suburb has become the Northwest’s nod to Southern California, a sort of soggy Beverly Hills crowded with showy homes and shining office buildings.

Bellevue’s rising fortunes passed by the Challises. Although Albert Challis specialized in fixing Jaguars, his own car was a Toyota. Their house, plain and prefabricated, stands two blocks from a row of elegant, $500,000 estates.

Beryl Challis, especially, noticed the good life just beyond her reach. “We didn’t have a lot of money, but she had an eye for quality,” her husband said.

One day in February, 1990, after seeing a face lift demonstrated on a local TV program, she announced that she wanted one.

“She thought she would make herself a little bit fresher-looking,” Albert Challis said. “A minor tuneup. She watched the television and saw what was done, and she thought it was kind of like going to the dentist.”

The $5,900 fee was hardly small change, but Beryl Challis promised to tap her own savings and sell her old jewelry. Albert Challis did not argue, and a few days later, she called the surgeon she had seen on television.

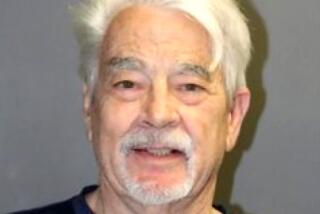

His name was Dr. Selwyn A. Cohen.

Handsome. Generous. Caring. A meticulous surgeon, a dedicated father of four. It is hard to find anyone, now that Beryl Challis is gone, to utter a bad word about Cohen.

He and his wife, Janet, came to Bellevue in 1981. Fresh out of a surgical residency at the University of Kansas Medical Center, he quickly built a thriving, one-man practice.

“He was one of our society docs,” said Diane Mackey, a hospital operating-room nurse. “He was a hit at cocktail parties, so gregarious.”

By all reports, he backed up his charm with competent work. At age 41, after 10 years in business, he had yet to face a malpractice suit, his nurses said.

Cohen performed the full range of modern cosmetic surgery, lifting faces, molding noses, pumping up breasts. And he did it with flair, making patients feel that they were not just having an operation but were entering the world of beautiful people.

In the carpeted lobby of his 11-room suite, patients could sip tea from china cups and gaze at a sculpture of Venus, goddess of love and beauty. Instead of paper hospital gowns, patients wore silk kimonos.

Beryl Challis was impressed.

“She went into it trusting him because of his prominence,” her husband said.

Cohen met with Beryl Challis twice before operating to examine her, find out what she wanted and have her sign a form acknowledging the risks of surgery.

But Albert Challis said his wife got more than she expected: “It was ghastly. He did far more extensive surgery than was agreed to.”

Cohen’s nurses said it was an ordinary face lift, nothing more.

Whatever was done, Beryl Challis felt miserable. She had been told to expect discomfort for about three weeks, but she described intense pain that never stopped, even after months.

“She said everything felt tight, like she was in an iron mask,” Albert Challis said. “She said it was a kind of searing, burning pain. Changes of temperature would make it feel like she was being cut with knives. Her skin started to dry, and veins started to appear on the surface.”

Ashamed of her looks, she rarely left the house, he said. She’d lie in bed for hours, moaning: “I wish I could die.”

Beryl Challis’ case comes as more and more Americans are sticking out their necks--and noses, lips, breasts and thighs--for cosmetic surgery. The American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons says the number of operations performed by its members increased 63% between 1981 and 1988.

At the same time, experts say, plastic surgery is growing safer. Malpractice insurance rates, which once put plastic surgeons into the highest risk category, have dropped recently in many states.

Perhaps 3% of face-lift patients experience discomfort, depression or excessive bleeding, said Dr. Ronald Iverson of Pleasanton, Calif., chairman of public education for the plastic surgeons’ society.

Fewer than 1% have chronic pain, he said, and even that is usually “just a small annoyance.” He and other experts said they had never heard of pain as severe as Beryl Challis reported.

More common, they said, is for patients to be unhappy with medically successful operations.

“It’s not unusual for people to have magical expectations,” said psychiatrist Marcia Goin, co-author of a book on the psychological effects of plastic surgery.

Although most patients with unrealistic hopes come to appreciate their improved looks, a few never accept that a new face or body does not guarantee a new life, Goin said.

Cohen’s staff believes Beryl Challis was in that minority.

“Visibly, she had a good result, but she couldn’t be convinced of that,” nurse Jan O’Brien said.

“She was a troubled woman,” office manager Barb Newton said. “She had other problems that had nothing to do with us.”

Her family rejects that. “My mother wasn’t crazy,” Christopher Challis said. “She was in pain.”

Cohen sent Beryl Challis to three other surgeons and a counselor.

Her appearance was “a matter of opinion,” said one of those surgeons, Dr. Gilman Middleton. He found no physical cause for her pain, but he did not rule it out.

“She was concerned about being over-tight, but in all reality I think it was blown out of proportion to what was there,” he said. “It’s difficult to know what was going on, even if you were there.”

There will be no malpractice suit, no further examinations to get at the truth. On April 15, Beryl Challis settled things her own way.

She went to Cohen’s office for a 5:30 p.m. appointment and left 30 minutes later, only to return after his staff had gone for the night.

Police believe that she persuaded Cohen to let her in, then pulled out a .38-caliber revolver she had purchased three weeks earlier. She fired repeatedly, emptying all five chambers into the doctor.

Cohen fell dead a few feet from the sculpture of Venus.

Half an hour later, Beryl Challis was home, dumping her medical records into the trash. At 9 p.m., she left the house, saying she wanted a hamburger. Albert Challis, growing suspicious, went into the bedroom and found a suicide note. He hurriedly drove to nearby burger joints but saw no sign of his wife.

When he returned home, she was in the bedroom, dying of a gunshot wound to the head. Nearby was a long letter addressed to Cohen, detailing her complaints.

It concluded:

“I have a wonderful husband and two lovely sons and everything to live for, but you have ruined my face and hair and mutilated my face muscles and put me in this constant pain. I feel that life is not worth living this way, and I will take my life. But it is you, Dr. Cohen, with your dreadful radical surgery, that has killed me.”

Five hundred mourners attended Cohen’s funeral, including many former patients. Dozens visited his office, offering condolences to his staff, then asking the inevitable question: Can you recommend another plastic surgeon?

Beryl Challis’ remains were cremated; her funeral was private. In the days after the shootings, as he had padded about his silent house, Albert Challis replayed the tragic events over and over in his head.

“This could happen to anybody,” he said. Although he understands all too well why people are drawn to plastic surgery, he said he hopes that they will consider the potentially cruel cost of vanity.

Beryl Challis ripped up photos taken after her face lift; she wanted to be remembered the way she once looked. But Albert Challis is haunted by a different vision of his wife.

When he returned home the night of April 15, a note was on the bedroom door. “Don’t come in. Call the medics,” it read.

“I went in anyway,” he said. “I shouldn’t have. She was lying face-up on the bed, a gun in her hand. There was a big hole in her head, and her eyes were staring out. She was breathing real fast and shallow . . . . “

He paused, tears welling up, then said: “I can’t get that image out of my head.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.