Gospel ‘Singers’ Give Religion a Good Rap : Changing times: One of the hottest trends in the $300-million-a-year Christian music industry was virtually unheard of a few years ago.

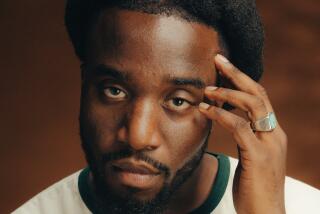

LAGUNA HILLS — Dancing energetically on stage before a crowd of cheering teen-agers, Chuckie P. clenches a microphone and belts out the words to his latest rap record.

The bass is pounding and the rhyme is catchy. But when it comes to the message, Chuckie P.--aka. Chuckie Perez--is miles away from the more famous rap artists of these times.

“You think I’m strange ‘cause I won’t do the wild thing. You call me a fruitie cat,” he sings before a crowd at a San Juan Capistrano church. “Well, I’m saving myself for the girl of my dreams. Tell me, do you have a problem with that?”

Perez, 22, the son of a Norco minister, is among a growing number of gospel rappers--Christians who use urban rap music to express their religious beliefs and traditional values.

Virtually unheard of a few years ago, gospel rap today is one of the hottest trends in the $300-million-a-year Christian music industry. Earlier this month, when the Gospel Music Assn. held its annual awards ceremony, there were two new categories devoted solely to rap.

Gospel rappers are a diverse group, mostly in their teens and 20s, who tackle varied issues, ranging from premarital sex, drug use and gang violence to the hypocrisy of segregated church services. They have played to large crowds at Knott’s Berry Farm, Christian teen-age music festivals and local churches.

“It’s not true you’ve got to have sex to have a good time,” said Kim Carino, a spokeswoman for a new teen label at Maranatha! Music in Laguna Hills, a Christian record company that helped pioneer contemporary Christian music in the early 1970s.

Gospel rap “focuses (on) Jesus as the answer to your problems without beating kids over the head with the Bible,” Carino said.

The budding movement has found supporters among the clergy and others within the Christian community who believe that gospel rap offers youths a much-needed, positive alternative to the sexual overtones and violence that pervade mainstream music.

Daniel Hahn, a Baptist pastor who runs a 250-member youth ministry at Mission Hills Church in Mission Viejo, said he plays gospel rap recordings at evening church programs--much to the dismay of some older, more traditional churchgoers.

“What concerns us are the (secular) lyrics that get pounded into minds of teen-agers,” he said. “So, for rap to come along and combine the rhythms with positive lyrics, that’s exactly what we’re looking for.

“If I were trying to help old ladies in Iowa I would probably use hymns, but if you throw a hymn at a kid in South Orange County, they’ll just walk the other way.”

Father Rod Stevens, director of liturgy for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange, said he encourages any artistic form that enables youths to express their faith.

“The fact that some people are using rap rhythms for sacred means--the church has absolutely no problem with it,” Stevens said. “It has been used for obscene purposes, but it is not in itself necessarily obscene.”

However, not everyone has welcomed this latest, unconventional form of religious expression. Dance has traditionally been a touchy topic within more conservative churches on the ground that it leads to secular evils. Further, rap music has been negatively associated in religious circles with such bands as 2 Live Crew--a hard-core rap group that fought obscenity charges in a Florida court.

“We’ve had to deal with everything from people calling us satanic to calling this devil music,” said Michael S. MacLane, vice president of Frontline Music Group, a Newport Beach-based Christian record company.

“Whenever you break tradition, people feel a little awkward,” he said.

At issue is whether rap, because of its secular roots, is incompatible with religious worship.

“Some in the Christian community oppose it because they say rap music is the style of the sinful world,” said Al Menconi, an evangelical minister in the San Diego area who publishes Media Update, a magazine that monitors trends in Christian entertainment.

“Therefore, they think tying Christian lyrics with this worldly music is an abomination,” he said.

Menconi dismissed such criticism: “Music is a language, and if you want to reach youth, you have to speak their language.”

However, traditional attitudes have prevented gospel rap from gaining a widespread following among Christian youth, according to record executives at Maranatha! and Frontline. They say many local Christian radio stations refuse to play gospel rap.

“A lot of it depends upon the background of the station manager,” said Ron Kopczick, a spokesman for the National Religious Broadcasters Assn., based in New Jersey. “A lot of times they don’t feel it’s in their personal taste.”

Programming executives at KYMS, an FM Christian station in Orange, maintain that they have nothing against gospel rap. But they rarely play it because, they said, the music does not appeal to their mostly adult listeners.

“Some people are going to be reached through Christian rap music; more power to them,” KYMS station manager Dave Armstrong said. “My personal feeling is that the Lord is going to reach different people through music in different ways.”

Without radio stations to expose youths to gospel rap, record executives rely on paid ads in underground religious publications, Christian youth music festivals and word of mouth.

Another obstacle to gospel rap’s reaching a broader audience is that the recordings are generally available only in Christian bookstores.

“Surveys have shown that only about 6% of dedicated Christians shop at Christian bookstores,” said Tom Coomes, Maranatha! president. “So there are going to have to be new alliances with Christians and mass marketing.”

For Coomes, the debate over the merits of gospel rap rings familiar. Two decades ago, Coomes, then a young musician, was among thousands of teen-agers, disillusioned hippies and beach people in the county who joined the Jesus People Movement.

Embraced by Pastor Chuck Smith, they flocked to the Calvary Church in Costa Mesa, bursting with excitement over their newfound faith and eager to express their love for Jesus. They came from across Southern California with their shoulder-length hair, ragged blue jeans and guitars, replacing traditional church hymns with new songs influenced by rock music.

Their songs would become the foundation for contemporary gospel music. Two of Smith’s followers, Coomes and Jim Kempner, would later form Maranatha! and Frontline.

But Coomes said the new converts were met with hostility by longtime church members.

“It was the same way, only it was Jesus music then, and the church said, ‘What is this?’ ” Coomes said.

Today, Maranatha! and Frontline are at the forefront of gospel rap. Between them, the two companies feature six of the estimated two dozen gospel rap artists in the country signed to record labels.

The musicians range in style from the rap of Chuckie P., who addresses premarital sex and drug use, to the street rap of PID (Preachers in Disguise), who confront Christians over such controversial topics as segregated religious services.

Chuckie P., who was raised in the nondenominational Church of the Rock congregation, for which his father is pastor, said: “I’m speaking on behalf of a lot of teens out there. Not just church teens but others with good morals who’ve been afraid to say what I’m saying.”

He said he wrote the title song from his album, “Do You Have a Problem With That?” based upon his own memories of teen peer pressure.

“People would offer me drugs,” he said, “and when I’d say no they’d say I was square. It used to bother me that I never had an answer for that.

“Now, I can come back and say, ‘Do you have a problem with that?’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.