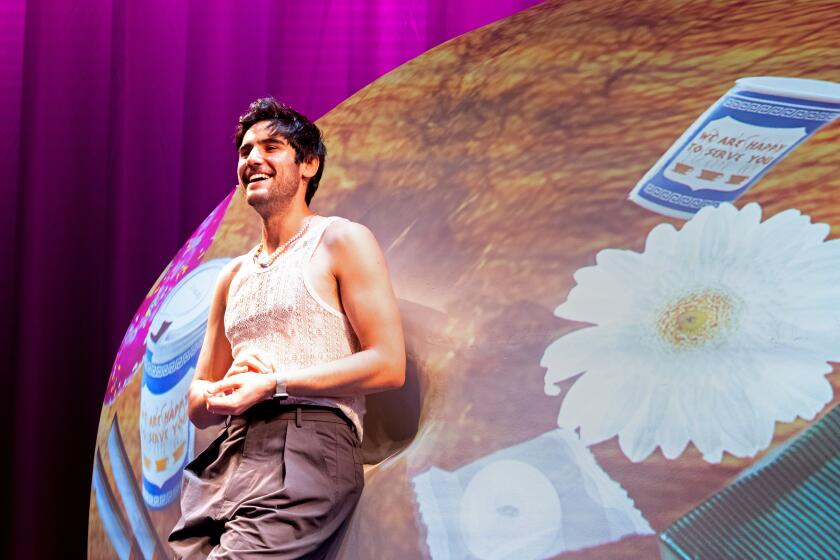

Don’t Ask Him ‘What’s New?’ : Getty Conservation Institute director Miguel Angel Corzo is committed to the past for the sake of our future

You could almost hear drums rolling and cannons booming when the People’s Republic of China and the Getty Conservation Institute announced plans to conserve China’s foremost sites of ancient Buddhist art: the Mogao and Yungang rock grottoes. The unprecedented collaboration was heralded as great good news on both political and cultural fronts.

That was January, 1989. But, five months later, after the Chinese government’s repressive reaction to student demonstrations in Beijing’s Tian An Men Square, the project was put on hold. It appeared that the towering stone sculptures, gilded clay statues and wall paintings that fill 545 caves in northern China would continue to suffer from erosion, pollution and neglect.

Now the project is under way again--with absolutely no fanfare. On-site research quietly resumed last fall, and Getty Conservation Institute director Miguel Angel Corzo recently set off on a tour of inspection. “I will be looking at progress of our monitoring efforts and holding a series of discussions with the Chinese Bureau of Cultural Properties. We will talk about further possibilities of cooperation and methods for management of the sites,” he said, shortly before leaving for China. “Conservation is not an isolated action. It’s no good to conserve if you don’t have a plan to manage the site.”

The Getty won’t tell China how to take care of its cultural property, the 48-year-old director says. “It would be presumptuous and arrogant of us to try to go out and preserve the cultural heritage of the world. What we can do is provide a significant amount of support and technical expertise as a collaborator within a partnership.”

As in other Getty collaborations, the Chinese will maintain the historic sites of Mogao and Yungang after an international team has determined how to slow the destructive forces of aging, weathering and pollution. Sandstorms, smoke, water and earthquakes have caused extensive damage to the Mogao caves, on the southwestern edge of the Gobi desert. Air pollution from local coal mining, ground water and salts have destroyed many carvings at Yungang, about 200 miles west of Beijing.

It’s an enormously complex, long-term project, but China’s Buddhist caves are only one challenge inherited by Corzo from his predecessor, Luis Monreal, who left the Getty last year. (Monreal resigned to work with UNESCO in Paris, but he now heads La Caixa, a Barcelona savings-and-pension fund that sponsors major cultural projects.)

The Getty Conservation Institute initially “created a presence and a credibility for itself” by tackling “high-visibility projects” and implementing them with a serious, systematic and sensitive approach to conservation, Corzo says. A 1986 conference on in situ archeological conservation in Mexico City, for example, assembled conservators and archeologists from around the world--”people who don’t usually talk to each other,” says Corzo, who helped organize the conference.

A highly publicized effort to restore wall paintings in the tomb of Nefertari, on the other hand, was “the first time the Egyptian Antiquities Organization permitted anyone to work on the wall paintings,” he says. “The reason they did is that we offered not only to conserve but to conduct a careful, systematic program of scientific research.”

The Getty throws its weight behind such projects only after getting affirmative answers to five questions:

* Is the project possible only with the support of the Getty?

* Will there be training opportunities for students in the region?

* Will the impact of the project be significant beyond the project itself? (Research on the Nefertari wall paintings, for example, applies to wall paintings in other sites, while knowledge gained in restoring Chinese Buddhist caves will help to save other damaged cave sculptures.)

* Will the project benefit not only the host country but enhance the Getty institute’s program of research and development?

* Will GCI have a real partner? (The institute does not give grants; it enters into partnerships with other institutions and agencies of foreign governments.)

The questions rule out most potential projects, but they are essential because conservation requires enormous human, financial and technical resources, Corzo says. The institute aims to maximize the impact of expenditures by leveraging funds and acting as a catalyst for international action.

Corzo has plunged into the institute’s established programs and he persuasively espouses its philosophy, but what thrills him most is the future. “I’m very excited about what we can accomplish. We’re building a dream for the 21st Century, a dream about conserving the past for our future,” he says.

“Why can’t young people get as excited about saving our cultural patrimony as about saving the whales?” he asks. Twenty years ago there was no public outcry about human destruction of whales, dolphins or tuna, he reasons, so who’s to say that people can’t be taught the value of our cultural legacy? From a purely practical standpoint, it would be far less expensive to revere and protect man-made treasures than to struggle to save them after they have been abused to the point of disintegration.

“I think of cultural patrimony like photographs of your grandparents. You keep the photographs at home in a special place. They represent your relationship to the past and a springboard to the future. If those photographs are down on the ground being trampled on, if they are vandalized, flooded, burned or ignored like our cultural patrimony . . . we lose symbols of the past and the hope of our children’s future. Like the photographs, cultural patrimony deserves a place of dignity, love and respect,” Corzo says.

Having expounded with missionary zeal, he suddenly smiles and says, “I get very emotional about this. It has always been my passion.”

Corzo’s passion was born when he was a boy of about 10 in his native Mexico, wandering through the pyramids at Teotihuacan. “It was about 6 in the morning and it was very foggy,” he recalls. As the fog lifted, the pyramids seemed to rise from the earth and he was struck by the majesty of the ancient city. “I asked myself, ‘Who thought of this?’ Who said, ‘I am going to build this’? These monuments are acts of human will and imagination. Our cultural patrimony is symbolic of the incredible creativity of mankind and the ability to transcend (mundane existence),” he muses.

Corzo might have been expected to pursue a career in the arts, but he entered fields that seemed more practical and were certainly more popular with the young intelligentsia. “I went into engineering, science and finance in college. With men on the moon, it was the thing to be in the ‘60s,” he says. He received a bachelor of science degree from UCLA and subsequently went to Harvard University as a Fulbright scholar, conducting research in finance, energy and international politics.

Returning to Mexico, he served as dean for academic affairs at the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana in Mexico City from 1974 to 1976, then held several government posts. Corzo never dreamed that he could combine his childhood passion with his academic training and practical experience, but he eventually moved into administrative positions that plunged him back into the arts.

In his most recent position, as president and chief operating officer of the Friends of the Arts of Mexico Foundation in Los Angeles, he organized “Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries,” the most comprehensive exhibition of Mexican art ever presented in the United States. The exhibition, which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and is now at the San Antonio Museum of Art (to Aug. 4), will be exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art from Oct. 6 to Dec. 29.

Under Corzo’s leadership, the foundation also has collaborated with the Getty Institute on the conservation of rock art in Baja California and the restoration of a mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros on Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles.

Now charged with charting the institute’s course, Corzo asks, “When we look back 10 years from now, what will we have created? The GCI Newsletter? A bunch of gray-cover publications?” He prefers “to prepare to deal with the future. I think of it like building a ship--creating a firm structure that can set sail in unknown waters with a sense of adventure.”

For literal-minded skeptics who have difficulty visualizing this vessel, Corzo offers a list of goals: Define future conservation needs in consultation with other specialists, establish a design to fulfill these needs and investigate legislation that might aid conservation.

Corzo wants to develop contacts with industry to learn better communication methods. “We are very bad marketing strategists,” he says. “We aren’t in it for profit, but we want more people to know what we are doing.”

He also advocates educating the public to respect and care for cultural patrimony. This includes everything from teaching children to sensitizing adults who unwittingly damage cultural treasures. “If a guide touches the surface of a wall carving or painting while leading a tour of an ancient site, say, 20 times a day, he can lay down deposits that will take two months to remove,” Corzo says.

The prospect of caring for the world’s cultural patrimony is daunting. There are 40,000 cultural monuments in Czechoslovakia alone and 30,000 of them need conservation, he says. About 20,000 pre-Hispanic sites in the Andes need attention. Around 6,000 churches have been restored in Mexico, but thousands more are in need. “Looking ahead to 20 years from now, many of the things we now call modern will be 100 years old. More and more things will need care, so we will have to make hard choices. We will have to decide how we will deal with what we keep and what we have to let go.”

But Corzo refuses to be overwhelmed. “I have a sense of opportunity and I’m having a lot of fun,” he confesses. “One should never lose the capacity to be astonished by human creativity.” If he had his way, he would restore that capacity in those who have lost it and instill it in people who have never experienced his passion. “The day that there is a demonstration in front of an art museum demanding more conservation is the day I will be satisfied,” he says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.