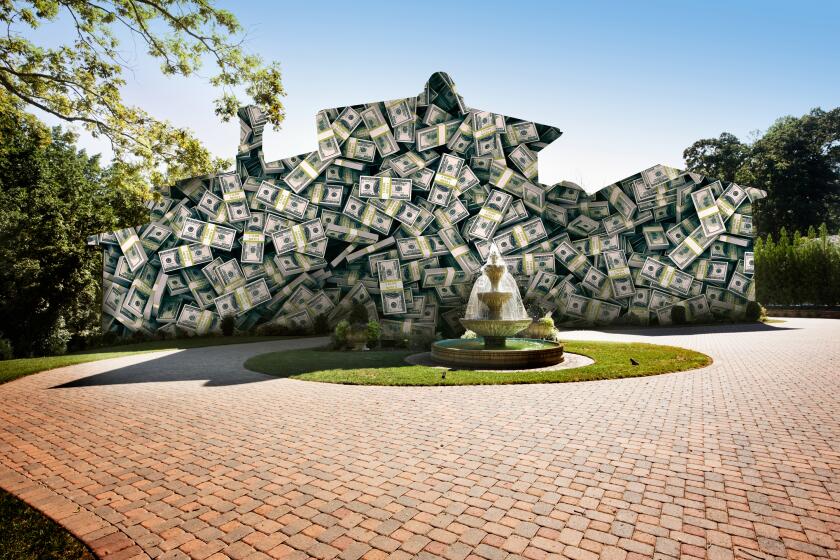

MULHOLLAND MANSIONIZATION : There Goes the Neighborhood : Growth: The picturesque rural route divides those who want to build luxurious estates and residents who like life better as it was.

Mulholland Highway is caught in a battle between preservation of its remaining natural resources and serving as a scenic country home to wealthy urban refugees.

The route, which runs through the heart of the Santa Monica Mountains in Calabasas, Agoura and Malibu, was named for William Mulholland, the Department of Water and Power chief who masterminded delivery of Eastern Sierra water to Los Angeles in 1913.

“It’s changing as we speak,” said Penny Suess, an area writer and one who would prefer to see the highway area’s natural elements remain. “It’s hard to watch the graders taking the hills down. Even if I had the money I’d never buy a mansion--they’re repugnant. I’d rather have a cabin in the trees.”

Suess, a resident of Seminole Springs mobile home park, said she enjoys walking along the highway, observing the natural plants and trees, and occasionally seeing wildlife. She worries that new residents won’t appreciate nature in the wild.

“I think the more suburban types are coming here now. A lot want to landscape their yards with lawns and use a lot of water. They want to get rid of the native plants--they consider them weeds.”

“While there is a certain type of opulence that can be good, I wish some of the new people here could design their homes well, more of a Frank Lloyd Wright approach of building with nature,” said Dana Gurnee, Suess’ companion.

But Alan Satterlee, who is building 20 $1-million-plus homes on 20 acres along Mulholland Highway, said custom estates enhance the views of the mountains.

“I’ve lived in the Mulholland corridor since ‘74,” Satterlee said. “Frankly, I thought it was boring to drive along Mulholland then and not be able to see any nice homes. I’m not saying I want cookie-cutter tract homes with street lights, but nice, custom homes tucked into the mountainside makes the view more interesting.

“Properties out here have escalated in the past 10 years,” he said. “The parks agencies have taken a lot of the land here and driven the costs up. A one-acre lot in the late 1970s would run you $5,000. Now it’s close to $500,000 for the same site. You wouldn’t build a 1,500-square-foot home on land that’s worth more than the house. Besides the land costs, there’s soils and geology work, grading, proper drainage and insuring for fire safety, and you’ve got a home the average person can’t afford.”

Satterlee said he plans to complete construction of the custom houses, which range between 5,000 and 7,000 square feet, in the next couple of years, “when market conditions are right.”

Los Angeles visionaries knew city dwellers would need to escape to the country even in the 1920s. Ground was broken for the roadway in 1923; by 1924, the highway opened with fanfare at Mulholland and Las Virgenes Road. A pack of Model T Fords drove under a banner that read: “55 Miles of Scenic Splendor--the Gift of Los Angeles to Her 1,250,000 Inhabitants.”

Courageous visitors drove the rugged mountain road to take in the spectacular mountain scenery, weekend at cabins in Malibu Lake, or to soak in the healing sulfur waters of Seminole Hot Springs. The hot springs resort served visitors until the 1960s, when it was razed to build a mobile home park.

As urbanization spread to Agoura and Calabasas in the late 1970s, local citizens, along with county and park service planning specialists, ventured to create a law protecting Mulholland’s unspoiled landscape. The statute never passed, however, and what protection there is lies in the County Board of Supervisors’ interpretation of zoning.

The county general area plans designate Mulholland Highway as a scenic corridor, but some preservationists complain that when it comes to protecting and enhancing scenic qualities, the plans have about as much strength as “a dog with dull or no teeth,” said Jess Thomas, an Agoura preservationist and owner of a storage yard on Mulholland.

Supervisor Ed Edelman, whose district includes Mulholland Highway, just directed the County Regional Planning Department to re-examine material from the original 1981 proposal, evaluate it, and reconsider adopting it.

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, an arm of the National Park Service, would prefer stronger zoning restrictions on building along Mulholland Highway.

“Ideally, we’d like it if no buildings were seen at all by drivers along that scenic corridor,” said Tony Gross, an environmental specialist for the recreation area. “It’s our responsibility to influence developers on this point, but their argument is, ‘you can only see the project for a moment.’ We are concerned about the cumulative effect of these developments-- that Mulholland will eventually look like a tunnel of homes.”

But Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Supt. David Gackenbach said much of the building is visible; he has had to deal with grading that extends into the national recreation area. Since some of the developments border the recreation area, he said his agency (via the taxpayers) is responsible for clearing the native brush for a required firebreak within 200 feet of the new houses.

One suburban-style project where the developer put in street lights went against the spirit of the recreation area’s intentions. There are few street lights along the road and local residents oppose putting in any more.

“Shining of urban and bright street lights inhibits the shyer species of animals like bobcats and badgers,” Gackenbach said. “The rangers do star talks at night up at Rocky Oaks Park (Mulholland Highway and Kanan Road) and at Peter Strauss Ranch (Troutdale Road and Mulholland Highway). Bright lights inhibit seeing the stars.”

But those who want to share in the charm of Mulholland’s beauty are willing to pay a big price to do it. Wishing to leave the smog and the rat race of city-living behind, wealthy city dwellers have discovered the relatively clean air and grand vistas that Mulholland is known for.

Batta Vujicic, a developer who heads a Westlake Village construction firm, discovered Mulholland Highway in 1982 and built his family’s dream home there.

A Yugoslav immigrant, Vujicic started his company in the South Bay during the 1970s, but grew tired of the hectic life there.

“We wanted to raise our children in nature and be close to the basics of the Earth,” said Rita Vujicic, Batta’s wife.

va,.4

Rita said she felt that Mulholland Highway resembled her native Italy, where she grew up on a farm. Batta said Mulholland reminded him of the country he read about in Western novels as a boy.

The Vujicics live with their six children on a 1 1/2-acre estate-ranch. Rita grows tomatoes and fruit trees, and raises about 30 chickens for eggs. The family has rabbits, cats and dogs.

Batta’s brother, Lubo, lives next door in a Tudor-style chateau with his family of five children. Rita’s sister lives in a peach-colored manor on an adjacent property. Three more villas are soon to be built in the area for Batta’s sisters who now live in the South Bay.

Vujicic is now grading property 70 acres across the highway for the anticipated construction of three mansions for himself and his family, and an Apostolic Christian church.

The builder will need to request a zoning change for his project, said Rudy Lackner, administrator of land-use regulation with the county planning department. Lackner added that the site is zoned for one house and that Vujicic has not yet applied for any zoning amendments.

“With me being a builder, I want to make sure all is sensitive and in harmony with the flavor of the area,” Vujicic said. “My commitment is to dedicate equestrian trails for the public to use.”

While Vujicic is ecstatic at being able to have his family housed around him in mountain villas, there are some neighbors who appreciate the increased value of their houses, and others who long for the way things used to be.

“I know we can’t stop development,” said Patty Elliott, a local resident, real estate agent and owner of an Agoura Hills hair salon. “This is one of the last commutable and unspoiled areas nearby L.A.

“We used to have a million rabbits and now we have a yard full of snakes,” Elliott said of changes brought about when the hills were denuded around her home.

When Elliott and her friend, Jesse Decker, bought their little ranch in 1987, they expected peaceful country living. Soon after they moved in, however, the bulldozers started up and pads were cut for 27 suburban tract-style homes on 18 acres--complete with curbs, gutters and street lights--surrounding their home. The project’s latest owner, Ezra Raiten, was killed in a plane crash last year and construction is on hold while his estate is put in order. Meanwhile, the hills around Elliott and Decker’s home remain bare with unfinished houses.

“I’m not saying I want to stop progress,” said Decker, also a local real estate agent. “But why take such a beautiful place and turn it into a suburb?

“There’s nothing more fantastic than taking a flashlight and walking to the Old Place (a venerable Mulholland Highway steak and clam restaurant) at night for dinner. You hear a rustle in the bushes and see that it is a coyote. The way of life is going by the wayside.”

Decker said he’d sell tomorrow to move to a place where he could sit on his back porch and not see rows of houses and be able to ride his horse freely.

“We’re not hostile to these people,” Decker said of other newcomers who have moved to his street, “but they bring their city ways. They don’t think about driving 50 miles per hour on our road. There’s dogs and kids that play in the street.”

“People buying these big homes have no room for horses,” said Elliott, who owns two. “I love this country; it’s gorgeous. And it’s being invaded because it’s beautiful. There’s nothing we can do to stop it. Our dream is for sale.”

“Let’s face it, the Mulholland Highway corridor was not intended to be this developed,” said J. Kim Coffin, a feisty former newspaper publisher who lives close to the highway. Coffin served on the citizens committee to form the scenic corridor ordinance that was never passed.

“It’s called ‘Blood Alley’ for the motorcycle crashes that happen on the winding stretches,” Coffin said. “Putting more cars on the road will only make it more dangerous.”

Dennis Washburn, the new mayor of Calabasas and one of those who worked on creating the scenic corridor mandate, said: “If we don’t act quickly, the construction will exceed not only the ability of roads and utilities to serve it, but our needs for respite as well. Our ecosystem could collapse.”

“You can listen to your heart here in the mountains,” said Kateri Alexander, a Mulholland Highway-area resident. “You can’t hear your thoughts with all the distraction of the city--smog, lights and traffic.”

While scenic means different things to different people, conflicting forces continue to pressure those who will decide Mulholland Highway’s future.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.