TV OPERA REVIEW : ‘Die Zauberflote’ According to Hockney

Mozart, Mozart everywhere. . . .

Like any musical institution proud of a place in Western civilization, the Metropolitan Opera did its part to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Mozart’s death this year. The part, however, didn’t quite turn out as planned.

The Big Event involved a lavish new production of “Die Zauberflote” to be first presented in New York on Jan. 10 and subsequently televised nationally on PBS. The original idea was to import a variation of the celebrated “Zauberflote” staged in Salzburg by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle--a production that had enlisted James Levine, the Met supermaestro, as decisive musical collaborator.

After Ponnelle’s untimely death, however, Levine & Co. turned to Werner Herzog, the adventurous cinematic auteur who had sailed with some canned Caruso up the Amazon for “Fitzcarraldo” and created a controversially picturesque “Lohengrin” in Bayreuth. Together with the Italian designer Maurizio Balo, Herzog devised a “Zauberflote” that, according to insiders, certainly would be fanciful and possibly would be magical.

Then something went mysteriously wrong. Last August, the Met announced that it was abruptly scuttling the Herzog production. A vague, not terribly convincing explanation from the management cited insufficient time to adapt the director’s concepts to the Lincoln Center stage. Enlightened rumor-mongers suggested that Herzog’s vision was too imaginative for conservative New Yorkers accustomed to the plush comforts of Zeffirelli realism.

Without a moment to lose, the Met went searching for an ersatz “Zauberflote,” one that would look pretty, come conveniently prepackaged, offer a modicum of prestige, cost less than a fortune, and ruffle no aesthetic feathers. The choice, no doubt, was easy.

David Hockney of Great Britain and Southern California--the chic, much lauded painter of pools, pals and pyramids--had designed a famous production for the tiny stage at the Glyndebourne Festival in 1978. It was enlarged for La Scala in Milan seven years later and eventually purchased by the San Francisco Opera, which soon loaned it to companies in Texas, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Michigan.

The Met simply called Rent-an-Opera, and the “Zauberflote” problem was solved. The third try, as Confucius observed, never fails. The colorful result can be seen on Public Television tonight. (The three-hour broadcast begins at 8 p.m. on channels 15, 28 and 50, at 9 p.m. on Channel 24.)

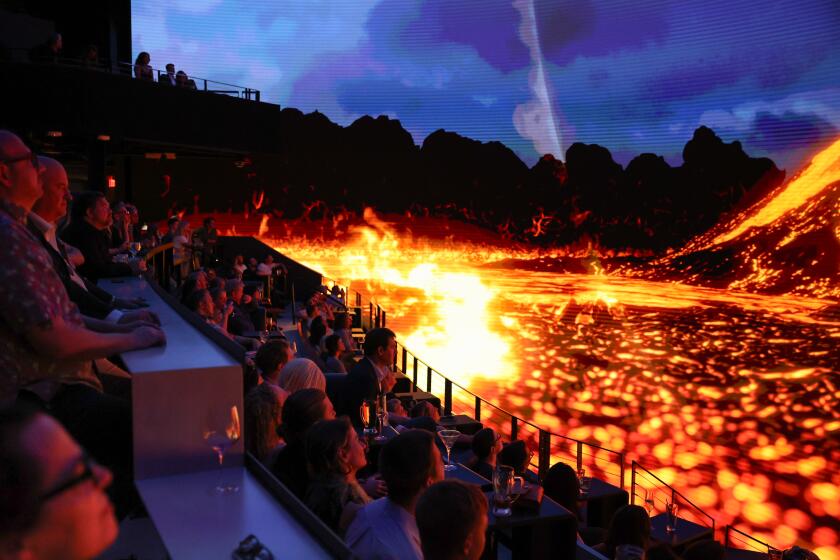

Hockney’s visualization of Mozart’s profound Singspiel --originally directed by John Cox and here entrusted to Guus Mostart--offers no interpretive provocations. It lacks both the charm and eloquence of Ingmar Bergman’s classic film version of 1974. Still, it exerts its own whimsical persuasion.

The Met has treated it well, and Brian Large usually keeps the cameras focused on the right place at the right time. The expressive scale may seem a bit ponderous. The gestures, both musical and dramatic, may seem a bit exaggerated. But that is natural. Subtle inflections and intimate nuances tend to blur at the Metropolitan Opera House, a cavern that accommodates 4,000.

Under the circumstances, one must be grateful for Levine’s sense of style, his heroic fervor and lyrical finesse. One must be grateful that Mostart’s Mozart moves without much gimmickry, pomposity or comic distortion. And one must be grateful that the uneven cast is strong--by current problematic standards.

Kathleen Battle, the limpid Pamina, exemplifies storybook purity and innocence. Francisco Araiza, her princely Tamino, exudes sympathy even when his once-pliant tenor shows signs of strain (did he really have to venture Lohengrin?).

Kurt Moll, the Sarastro, proves that the dignified basso-profondo is not an extinct species after all. Luciana Serra, the stratospheric Queen of the Night, hits the dreaded top F with menacing force, even though she is not at her estimable best here.

Manfred Hemm makes an agile, pleasant peasant of Papageno, though his characterization is cut from stock cloth. Barbara Kilduff complements him as a cute Papagena (what other kind is there?).

Heinz Zednik, the unusually nasty Monostatos, endures the racist slurs of the spoken text but escapes them in the obfuscating subtitles. Andreas Schmidt, the youthful High Priest, approaches his brief but crucial scene with the sensibility of a Lied specialist. The Three Ladies--Juliana Gondek, Mimi Lerner and Judith Christin--are admirably mellifluous, the three choir boys masquerading as genii admirably earnest.

Still, it is Hockney who steals this show. The screen takes kindly to his deliriously clever evocation of naive vistas, his deceptively symmetrical temples and ruins, his adorable menagerie of not-so-wild animals and his wistful manipulation of ancient theatrical devices. If anything, his sets benefit from the flattering perspective imposed by the long shot.

The PBS presentation is hosted, not incidentally, by none other than F. Murray Abraham--a.k.a. Salieri. Amid brief flights of gushing hyperbole, he informs us that “Die Zauberflote” happens to be his favorite opera.

Amadeus would have cackled.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.