Exchange Yields Another Effective Show : Exhibit: ‘A Sense of Place’ comes alive through the eyes of a contemporary and a historic artist.

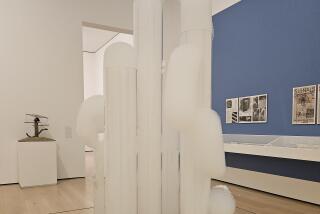

SAN DIEGO — Ann Hamilton’s installation “Linings” (1990), at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, greets us first with a pile of wool boot liners, useful but unused; then with a large structure, an enclosure whose blanket-wrapped walls promise warmth and security. But within, the room bears no roof, and the thick, quilted exterior has given way to interior walls of cold, smooth glass.

Handwritten musings on the natural world and man’s place within it paper the interior walls, behind the skin of glass tiles. The author of the text, naturalist John Muir, reveled in direct, profound experiences of nature, while Hamilton has created an environment that denies that same physical and emotional contact with the Earth. She lay sinuous grasses beneath our feet but has allowed us to feel only the glass that covers them.

Hamilton’s work, a recent acquisition by the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, is on view in an exhibition with the theme “A Sense of Place.”

Hamilton evokes not so much a sense of place as a sense of alienation from a place: the Earth itself. In the context of this exhibition, the third and final phase of an exchange program with the Timken Art Gallery, “Linings” is especially powerful.

As with each segment of the exchange program, works from the Museum of Contemporary Art are exhibited alongside those from the Timken’s collection. The exhibitions take place at both venues. Hamilton’s work has been paired with the Timken’s “Pastoral Landscape” by the French painter Claude Lorraine (1600-1682). A fine example of a neoclassical sensibility, the painting shows shepherds and robed women within an ideal, luminous landscape. Where Hamilton’s work conjures a sense of distance from the Earth, Claude’s presents an image of unity with nature, an environment of ease and promise.

The two works are radically different in both message and means, and their juxtaposition helps each reveal itself clearly and distinctly. Such daring and extreme contrasts are what makes the Timken/SDMCA exchange program so compelling.

At the Timken, Eastman Johnson’s 1880 “The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket,” a panoramic scene of communal labor, hangs beside an installation by contemporary, San Diego-based artist Patricia Patterson, from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art. In “The Kitchen,” as in all of Patterson’s work, color announces place. Here, table and chairs rest on a vibrant blue and yellow checkerboard tile floor, and on the walls hang two broad, vividly painted views of the Irish kitchen interior on which this installation is based.

In one image, a couple embraces warmly at the table, and in the other, the man sits pensively, gazing into the distance, while his piebald horse grazes casually in the yard just behind him. Patterson has framed both images in wide wood frames painted intense hues of blue, green and red-orange.

What she achieves and what the 19th-Century American painter Johnson does are actually quite akin in spirit. Though Johnson’s light is warm and refined and Patterson’s palette can be sharp, both define a specific place in terms of its sensuous, human qualities. Both Nantucket’s cranberry bog and the Irish couple’s kitchen are places of both labor and pleasure, family and community intimacy. In both, life is experienced with hearty immediacy.

Several still lifes round out the offerings at the Timken--contemporary works by Basque artist Andres Nagel, a 17th-Century Dutch painting by Pieter Claesz and another painting by Patterson--and these, too, provide rich ground for comparisons and contrasts. This segment of the Timken/SDMCA exchange was well curated by Grant Holcomb, former associate director of the Timken and now director of the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, N.Y.

Though “A Sense of Place” has been billed as the final segment of the exchange program, let’s hope the concept lives on. Such fresh, thoughtful juxtapositions of contemporary and historical works are as jarring and surprising as they are enlightening.

The exchange exhibition continues at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, 700 Prospect St., La Jolla, through Aug. 4. Hours are Tuesday through Sunday 10-5, Wednesday 10-9. The show continues at the Timken Art Gallery in Balboa Park through Aug. 7. Open Tuesday through Saturday 10-4:30, Sunday 1:30-4:30.

For the past 30 years, Tom Wesselmann has played off the slick, seductive strategies of advertising in his Pop art collages and paintings. At times silly, at times slightly cynical, the New York-based artist’s work has become firmly lodged into the canon of American art of the ‘60s.

But what does Wesselmann have to offer in the 1990s?

His current show at the Tasende Gallery yields a discouraging answer. Wesselmann’s art is sweet as a Popsicle--but no more nourishing. Wesselmann no longer builds his compositions from billboard imagery and advertising fragments, but his work has retained its polished, commercial character nonetheless. He now translates his sketches of female nudes, still lifes and landscapes into “steel cutouts,” then paints these tracery-like drawings in metal with his trademark primaries: vibrant lipstick red, blond yellow and Crayola flesh.

Though the cutout technique in itself is appealing, none of Wesselmann’s images are. His floral still life and fruit bowl are plain and predictable, his landscapes mundane, and his nudes are at best benign, at worst sexist and offensive. Drawing on a Playboy vocabulary of poses and expressions, Wesselmann’s nudes are all nipples and lips. Rarely do they have faces or personalities. They simply flaunt their bodies in that tired, sex-kitten mode of pinups and cheap erotica. Like the beer cans and automobiles in his earlier work, Wesselmann’s nudes are processed and packaged for easy consumption. This approach may have been fresh and biting 30 years ago, but not today.

Tasende Gallery, 820 Prospect St., La Jolla, through Aug. 24. Open Tuesday through Saturday 10-6.

CRITIC’S CHOICE: SANTIAGOVACA’S ENERGY, FEAR AND RAGE

Santiago Vaca has lived in the United States since he was 14, but his work still carries the strong imprint of his Latin American heritage. Vaca, who was born in Ecuador and now lives and teaches in Chicago, wields his paintbrush as a weapon of his own against obscene acts of military violence, political oppression and colonialism. His paintings--on unstretched canvas, walls and floor--fill the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park with energy, fear and rage. Vaca’s potent work remains on view through Sunday. Hours are noon to 5 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.