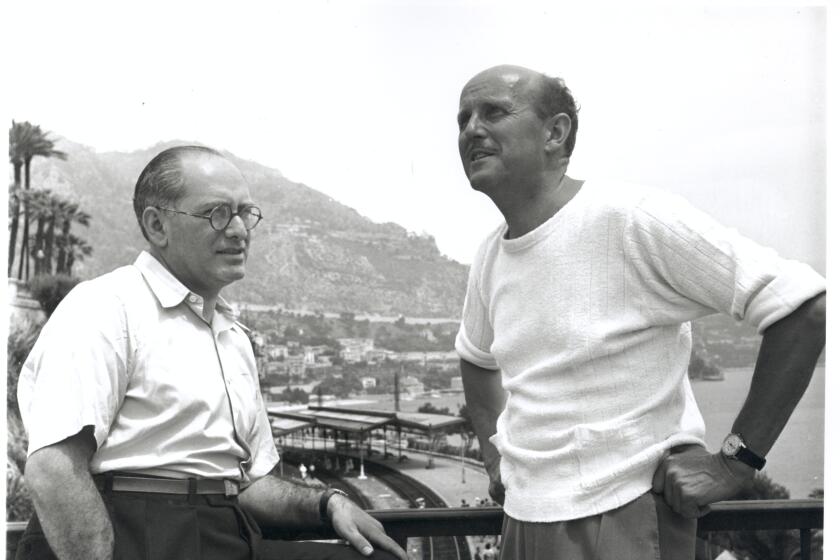

The Americanization of Arthur Hiller : Movies: The American Cinematheque is honoring the Canadian filmmaker this weekend with screenings of ‘The Americanization of Emily’ and ‘Love Story.’

Arthur Hiller, who is being honored by the American Cinematheque with a retrospective of his films this weekend at the Directors Guild of America, was 24 and working toward a master’s degree in psychology at the University of Toronto when it struck him that he wasn’t doing what he really wanted to do.

“I was interested in communication, that was why I was studying psychology,” Hiller said the other afternoon in his bungalow on the Universal lot. “Then I realized that if I wanted to communicate, the place I ought to be was in communications.”

Hiller, whose films include the phenomenally successful “Love Story” and such critical and/or commercial successes as “The Americanization of Emily,” “The Hospital” and “Silver Streak,” betook himself with nice Canadian directness to the office of the Canadian Broadcasting Co. and asked a receptionist whom he should see about getting a job.

“By sheer luck,” Hiller says, “she didn’t send me to personnel.” Instead she steered him to the head of the service, who sent him to the man in charge of public affairs broadcasts. “Three weeks later I was directing radio shows. What everybody says is true: You have to be lucky. Luck won’t do it all, naturally, but it’s tough without it.”

The radio work led to directing television documentaries and docudramas, then to an invitation from NBC to work in the United States. He made a lot of episodic television, including “Gunsmoke” and “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” and then did his first feature, “The Careless Years,” in 1957.

The film he prizes above all the others is “The Americanization of Emily,” a 1964 anti-war comedy written by Paddy Chayefsky from a novel by William Bradford Huie about a love affair between Julie Andrews as a British war widow and James Garner as an American officer with no heart for war.

“It’s the only one of my films I can sit through and not want to redo while I’m watching it,” Hiller says. The film almost didn’t get made. Producer Martin Ransohoff had had several writers try scripts. The idea was to lighten a dark book and give it a kind of “Yank at Oxford” feeling. Chayefsky was flown in from New York to discuss the project and turned it down.

“Then, on the flight back to New York, he saw how to do it, called Marty and a few days later sent a 40-page treatment. It’s the only film I fought to do, but Marty kept saying, ‘You’re too young, kid.’ He tried seven or eight other guys who didn’t want to do it or weren’t available, and he finally said, ‘OK, kid, it’s yours.’ ”

The film was criticized as anti-American but Hiller says, “It was never anti-American. It’s anti the glorification of war. Don’t make war seem so wonderful that kids want to be heroes; that’s what it was saying.” Hiller fought to make it in black and white, understanding that, as has often been observed, World War II was fought in black and white (in news pictures, newsreels and magazine coverage). “We had a struggle, because television was already demanding color. But we won.”

“Love Story” was another film that almost died before birth. “Paramount was in rocky financial shape. They’d sold off part of the lot and moved their offices to Beverly Hills--although I never understood how they figured to save money that way. But Bob Evans, who was running the studio then, loved the project. And he said we could make if I would swear --and I literally had to swear--that I would bring it in for under $2 million.”

It came in $25,000 under budget and Hiller insisted on using $15,000 to go back to Boston for some additional scenes. “We got there in the worst snow storm in 20 years and we had to improvise everything: snowball fights, making angels in the snow.” (The small crew didn’t know what Hiller meant when he suggested it, but Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal knew: lying flat in the snow and moving your arms and legs to create angelic patterns.)

At one point Hiller & Co. were improvising a tracking shot, shooting from the rear of a van. The exhaust fumes kept getting in the way, so Hiller and the producers found themselves pushing the van along a sidewalk.

Although “love means never having to say you’re sorry” became the joke-line of its time, “Love Story” joined “American Graffiti” as one of the largest-grossing films to that date in relation to its cost.

The tribute to Hiller began Tuesday night with a preview of his latest film, “Married to It,” a comedy-drama about three New York couples (Beau Bridges and Stockard Channing, Robert Sean Leonard and Mary Stuart Masterson, and Cybill Shepherd and Ron Silver) from a first produced script by Janet Kovalcik.

“It’s being promoted as a comedy, and it has to be,” Hiller says, “but I like to think of it as a dramedy, because there’s some tough stuff about the problems of staying married.”

Hollywood, which feels safer typecasting its directors as well as its performers, early on recognized Hiller’s aptitude for comedy, especially comedy with a sharp edge, as in “The Hospital,” which he did from another Chayefsky script. (“And what you saw was his first draft,” says Hiller. “If we changed as many as six lines, I’d be surprised.”)

His other comedy successes include “Outrageous Fortune” with Bette Midler and Shelley Long and “The In-Laws,” with Peter Falk and Alan Arkin. A drama of which Hiller is particularly proud, Maximilian Schell in Robert Shaw’s “The Man in the Glass Booth,” originally made for the American Film Theater series, will be shown in videotape format, as will “The Careless Years.”

Hiller has just now finished shooting “The Babe,” with John Goodman as Babe Ruth. “Finally I’ve had a chance to do a drama again,” Hiller says. The film is less about baseball than about the Babe’s two marriages and his often excessive love of life. He is less than unfailingly likable, and the ending, Hiller predicts, will be a jolt.

The director, Hiller says, is not far from the psychologist he once thought he’d be. “You have to be an expert in human relations. You’re dealing with all kinds of people, very talented people, and you’ve got to create a climate where they can do their best. You’re figuring out how to get something from them that even they may not know they can do.

“Barbara Harris came to me after ‘Plaza Suite’ and thanked me for the performance she gave. I said, ‘What do you mean, you gave it.’ ”

For one shot in “The Babe,” the camera begins on Ruth’s legs as he steps down into the dugout, then pans up to full figure. “After a rehearsal, I said, ‘John (Goodman), your legs have got to be more dejected.’ We both laughed. Then we did a take, and his legs were more dejected. Don’t ask me how.”

Like many an admired director in film history, Hiller prefers to respect the material and let it and the actors speak for themselves. His style is unobtrusive, and he seldom draws attention to himself with ornate angles and tricky camera moves.

At that, in “The Hospital” he covered five pages of dialogue in one long, complicated dolly shot. “It took four hours to set up and 17 takes. George (C. Scott) was perfect in 12 of them. The others were technical problems. I wanted the film to have a semi-documentary look, as if the viewers were peeking around the corner at something they probably ought not to be seeing. I think you could call that style good-messy.”

Not long ago, Hiller was telling Gregory Peck that he had been honored at both the Cairo and Montreal film festivals. “Ah, yes,” said Peck, “that’s what comes of having gray hair.” Hiller, born in Edmonton, Alberta, is now in his second term as president of the Directors Guild of America, leading the guild’s campaign for laws (common in Europe) protecting the artist’s creative rights: for example, the director’s right to protect his film from colorization or mutilation.

The retrospective opens tonight with a double-feature of “Plaza Suite” and “The Out of Towners.” “The Americanization of Emily” screens Saturday night at 6, “Love Story” at 3 Sunday afternoon.

Information: (213) 466-FILM.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.