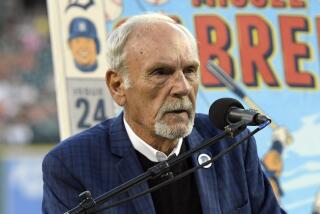

Leyland Thankful for Minor Miracles : Pirates: After years with farm teams, manager has taken Pittsburgh from 64-98 to 98-64 in five seasons.

PITTSBURGH — It is an afternoon in early September. The man considered perhaps the best of baseball’s new breed of managers is preparing as he always prepares for a Saturday night game in the middle of a pennant race.

Jim Leyland is sitting in his underwear, in his office rocking chair, watching college football on television.

“Hey,” he says, “it ain’t like I’m important.”

He smiles, and the lines on his gaunt face deepen. Those lines lead to Jamestown, and Rocky Mount, and Bristol, and Clinton, and other cities where he managed and played for 18 minor league seasons.

There is a rasp in his voice from smoking too many cigarettes. There is a tint in his smile from too many cups of black coffee.

“Last year I quit both things,” he said. “But I couldn’t keep it up. This season has been too tough. You know how it is.”

Hailed as the perfect leader for the modern-day major leaguer, Leyland has managed the Pittsburgh Pirates to within one game of their first World Series in more than a decade.

But he has reached this point with a style that reeks of wrinkled uniforms and 10-hour bus rides and splintered bleachers. He has done it not with a computer, but a memory.

It is an indelible memory of a time when coffee and cigarettes constituted his paycheck, a time when he drove the bus and taped the ankles and did nothing more important than teach boys about men.

“I am the kind of manager I am because of the minor leagues,” Leyland said last month while leading his team to the best regular-season record in baseball. “I am also the kind of person I am because of the minor leagues.”

Leyland will be in the national spotlight again tonight when the Pirates, with a 3-2 lead, attempt to finish off the Atlanta Braves in Game 6 of the National League championship series at Three Rivers Stadium.

If the Pirates win, Leyland will be one of the heroes. He skillfully worked his clubhouse after the Pirates fell behind, two games to one, then skillfully working his pitching staff in the late innings of Games 4 and 5.

“So I make a pitching change now and then, so what?” Leyland said. “The rest of the time, I just watch.”

Leyland is extraordinarily humble, because he knows what it is like to be humbled. He saw it happen to himself and others during those long years while working for the major league job that was finally given to him in Pittsburgh in 1986.

“I’ll never forget the first time I had to tell a kid he was released,” recalled Leyland, 46, who began managing in 1971 after a seven-year career as a minor league catcher. “I couldn’t even look him in the eye. I was looking down, saying to myself, ‘Please, please, help me say the right words.’

“Then I looked up, and the kid was bawling. Once you see that, you don’t ever forget what it means to be a part of this game.”

Leyland has managed players who suffered nervous breakdowns. He has dissuaded players from leaving the team because they missed their girlfriends.

If he looks calm when walking to the pitching mound to make a change, it is because he has already seen the worst that can happen out there.

Once, while managing a game on a cold day in Wisconsin, his pitcher hyperventilated and collapsed on the mound. He was wearing eight sweat shirts.

“To be honest with you, I miss those days,” Leyland said. “I know I have a lot of things now that I never had--like furniture--but I still miss those days.”

Leyland misses men like “Growler,” an elderly fellow named Earl Fenn who used to follow his teams at Class-A Clinton, Iowa, in the early 1970s.

Leyland so appreciated Growler’s loyalty, he would stop the team bus in front of his house before trips and give him a ride to the games. On the way home, he would drop him off at his doorstep.

“Growler used to sit right behind home plate, and we had this sign,” Leyland said. “If he thought I should get somebody ready in the bullpen, he would light a match.”

Several years later, while coaching for the Chicago White Sox, Leyland drove to Clinton and visited Growler. A couple of weeks later, Fenn died.

“Somebody like Growler, this is what is great about baseball,” Leyland said.

During the winters after those minor league seasons, Leyland would return home to Perrysburg, Ohio, the small town outside Toledo where he was born.

He would live with his mother and father in the modest frame home where he grew up in a family of nine. Even at 40, he did this.

He would talk and dream of one day reaching the major leagues. And he would not be questioned.

“I thought, someday, somebody would see his determination and give him a chance,” said his brother Bill, 51, who works for a muffler manufacturer and lives in Perrysburg, like everyone in the family but Jim.

“The way we were brought up, our father taught us that nothing comes easy, you had to keep working for everything,” Bill added. “That’s still the way we are.”

The Leylands’ father spent his life in a glass factory, returning every night to a house that never seemed big enough. It was his lessons that have shaped Jim’s philosophy.

“My dad taught us that everyone is equal, no matter what you achieve in life,” Bill said. “We were no hero-worshipers when we were children, and so we don’t really look at my brother any differently today. And I don’t think he looks at himself differently, either.”

That was obvious last winter when Jim was honored in Perrysburg after leading the Pirates to the National League East championship. By the time the town’s coaches and doctors had finished giving their laudatory speeches, it was getting late.

“So when it came time for Jim to talk, he just said a few words,” Bill said. “The program had already lasted pretty long.”

When Jim Leyland became the Pirates’ manager in the winter of 1985 after serving as third base coach for the Chicago White Sox since 1982, there was also not much he could say.

The team had won 57 games the previous season. Leyland had few established players, and little chance.

In his first season, they went 64-98. This season, five years later, they went 98-64.

“Do you realize how those numbers have been reversed?” Leyland said last week, as if he couldn’t believe it himself. “I think that probably says something.”

It says Leyland has somehow reached his players. This, despite the problems caused by the meteoric rise of several stars and their salaries.

This spring, in what may be the most famous incident of his managing career, Leyland publicly scolded star Barry Bonds for causing problems with a photographer because Bonds was upset about his salary. The incident was captured by television cameras, and the baseball world praised Leyland for standing up to a problem player.

Leyland, fittingly, did not agree with the baseball world.

“Everybody was making me out to be some kind of pioneer in that thing, but I just reacted, and 10 minutes later it was over,” Leyland said. “As long as I am here, I will do what I think is morally right. If it makes people mad, fine. But I don’t want to be sitting there after I am fired and say that I wish I’d done something more.”

Today, even Bonds agrees that what Leyland has done is special.

“Jim is great, he’s the one who holds us together,” Bonds said. “Nobody is treated special, nobody is treated different . . . and he never asks us to win. He only asks us to be prepared, and to have fun.”

Leyland is best at assigning players roles, then using them in those roles. He rarely puts his players in a position to fail, whether it be sending up the wrong pinch-hitter or leaving in a relief pitcher too long.

And Leyland makes everyone feel wanted, which has particularly helped him in his bullpen, where even journeyman Roger Mason can be left in a playoff game during the ninth inning and pick up a rare save, as he did Monday.

“All I try to do is give everybody a chance to be a hero,” Leyland said.

Many think he worries about his players too much. Last July, on a charter flight home from Cincinnati, the Pirates were forced to make an emergency landing because Leyland was experiencing an anxiety attack.

And the Pirates had just swept a four-game series from the Reds.

“It was like somebody jumped out from behind a tree to scare me, only, I couldn’t stop being scared,” Leyland said.

Subsequent tests showed he has a sound heart, and he rejoined the team the next day. He still smokes 1 1/2 packs of cigarettes a day, he still drinks quarts of coffee, and, this being the joy ride of his lifetime, he will make no apologies.

“I’m not going to change a thing, and why should I?” he said. “Man, you get into a big game in the bottom of the ninth with two out and men on base . . . you got a problem if your heart ain’t pumping fast.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.