Jazz Musician, No Retiring Type, Makes His Move and Gets Back Into Swing of Things

When vibist Charlie Shoemake closed his improvisation studio in the spring of 1990 and moved from the San Fernando Valley to the small town of Cambria, on the central California coast, retirement was not on his mind.

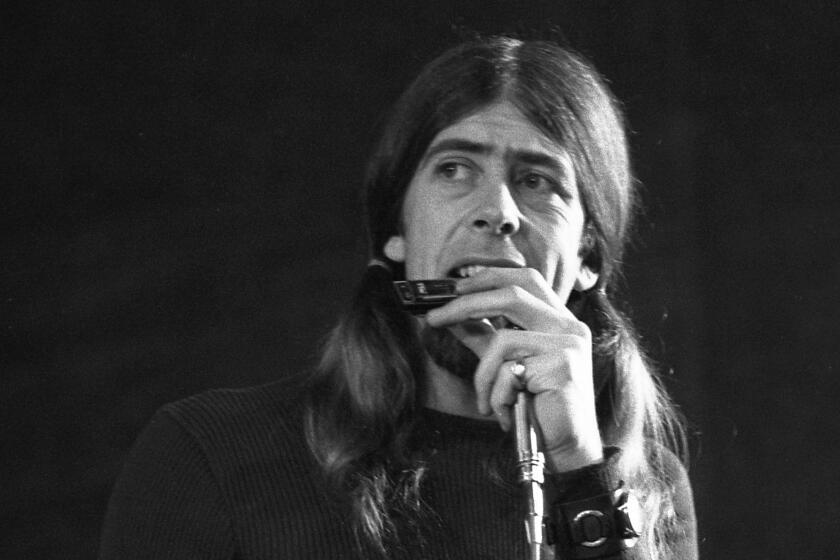

“Just the opposite,” says the 53-year-old vibraphonist, who, along with his wife, singer Sandi Shoemake, appears Friday at the Jazz Bakery in Culver City. “I wanted to get back into playing.”

Shoemake’s career had been pretty much on hold since 1973, when he left pianist George Shearing’s quintet after a stint of seven years on the road, and opened a studio in a small room in the ranch-style Sherman Oaks home that he shared with his wife and their son, Tal.

“I wanted to be at home with Tal and Sandi, and I didn’t want to go back to working in the recording or TV studios, which I had done before joining George. I hated that,” he says in a recent interview. “So all the years I was teaching, I was a sometime artist. I played around town, made a few records for Muse, Discovery, Pausa and Chase Music Group, but not to the exclusion of teaching.”

Shoemake shut down his studio because his son had married (the vibist is a grandfather now), and he began to feel different about teaching.

“I wasn’t enjoying it that much, especially the last years,” he says. “The students were less serious. A lot of them wanted to play like a master without practicing. I had a reputation for turning out talented players, but too many of them didn’t want to know that everything that’s worthwhile takes hard work.”

But you don’t just jump from one career to another.

“It’s taken a lot longer to get started than I thought, but I should have realized that. This is my fourth career move, and each one, though ultimately successful, took a while to get going.”

His initial career was as a studio pianist, and then as studio vibist, Shearing sideman and private improvisation teacher.

The horizon, however, is not completely bleak. The Shoemakes have booked a few concert/clinic dates at Bay Area colleges in the spring, and drummer-record producer-talent booker Bill Goodwin, now with Phil Woods and a longtime friend, is setting up some East Coast dates for next year.

Of more immediate interest is a series that the Shoemakes will be part of at the Hamlet, a restaurant and lounge in Cambria. These once-a-month concerts will feature top players from the Los Angeles area, and possibly musicians traveling from New York.

The first concert, set for Nov. 17, features guitarist Ron Eschete, bassist Luther Hughes and drummer Paul Kreibich, who will also appear with the Shoemakes at the Bakery.

That threesome, along with pianist Billy Childs, recorded several selections on Shoemake’s latest release, “Strollin’,” on CMG. The album also spotlights Sandi Shoemake and Bill Holman’s Orchestra.

“We had two things in mind for the album: using Bill’s band--he’s great, a legend--and having a small group present a tribute to George Shearing,” Shoemake says. “And it features Sandi, my favorite vocalist. Sandi and I will be taking Bill’s arrangements with us when we travel to colleges, so that we can perform that material with the school bands.”

At the Bakery, Shoemake’s repertoire will draw on tunes from “Strollin’ ” as well as some standards and jazz classics, such as Tadd Dameron’s “Hot House,” a tune that Charlie (Bird) Parker often performed.

As with many jazz musicians, Shoemake names Parker as one of his idols. Bird was one of the architects of the jazz movement called be-bop, along with pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie.

But before Parker, in Shoemake’s life, there loomed another idol, a non-musical one who had possibly even more impact than the saxophonist: baseball player Ted Williams.

The Boston Red Sox slugger won the American League batting crown six times, was the last major leaguer to bat over .400 for a season (.406, when he won his first batting championship in 1941) and was twice selected as the league’s Most Valuable Player (1946 and 1949).

“He was it ,” Shoemake said. “He was like God, and he still is. He stood for absolute perfection. He achieved what he did by having talent and also by working harder than anyone else.”

Before his teen-age years, Shoemake, living in Houston, began following Williams’ career. He saw him play for the first time in 1947, when the Red Sox came to Houston before the baseball season. And what he learned deeply impressed him.

“He practiced incessantly,” Shoemake says. “He took extra batting practice; he kept a file on every pitcher, he made it a science.”

So when Shoemake--a former Houston All-City baseball player who himself had a successful tryout with a St. Louis Cardinal farm team but eventually decided to play music instead--embarked on a quest to understand jazz after he had moved to Los Angeles in the mid-’50s, he used Williams’ methods to analyze the music of Parker, Powell and others.

“I wanted to get to the absolute bottom; I tried to take it apart,” he says. He copied the recorded solos of the jazz greats, and of Parker in particular, and transcribed them on paper. “I wanted to know all the things he was doing that, when put together, made such powerful statements.”

Little by little, Shoemake amassed a collection of transcribed solos by the likes of Parker, Gillespie, Powell, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Fats Navarro, Hank Mobley and other giants of the modern jazz idiom. He used these solos first and foremost to teach himself how to play, then later employed them as the basic texts for his studio.

Today, Shoemake, who was featured on the soundtrack of Clint Eastwood’s film “Bird,” estimates that he has more than 600 solos in his files. And, though he says he knows the music inside out, he keeps gathering new--well, actually old--material.

“I just like something fresh to play,” he says. And so he is continually transcribing, slowing the records down so the music, which is often played at extremely fast tempos, can be heard accurately.

Shoemake feels that in Cambria, relieved of the pressures of teaching, he’s finally back to the reason that he got into music in the first place: because he loves it, not because it might be financially lucrative.

“I have this Don Quixote streak,” he says. “I thought that being a jazz artist was going to be great. It was noble. But it was hard to find work, and I did things that had more economic opportunity. I didn’t like doing them, like the studio work, but I had a family to raise. I think that anybody who gets into music for money is a moron. I can’t understand it. If money was the most important thing, why not get into the financial world? That’s where the real money is.”

Vibraphonist Charlie Shoemake and singer Sandi Shoemake appear 8 p.m. Friday at the Jazz Bakery, 3221 Hutchison Ave., Culver City. Tickets: $15, includes dessert and coffee. Call (310) 271-9039.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.