Black S. African Fights Sanctions : Diplomacy: First secretary of embassy in Washington says actions, although well-meaning, have backfired in his country.

WASHINGTON — Like many diplomats who populate Embassy Row, Paul Jacobs has a courtly, nonconfrontational style, the sort of smooth demeanor essential to the art of diplomacy.

He is also a pioneer of sorts, a symbol of the fundamental shift that has taken place in his homeland. Jacobs is South African. He is also black. That is a rare combination indeed.

The comfortable trappings Jacobs enjoys as an emissary of President F. W. de Klerk are a far cry from his humble beginnings as one of nine children who lived off the proceeds of a family-run bootleg liquor operation in a teeming black neighborhood of Pretoria.

But he developed a passion for education, not only as a means of bettering his own lot but also that of South Africa’s black youth. Before coming here, he spent 35 years in the South African public school system.

But Jacobs’ passions are not limited to education: He also is an unswerving opponent of white supremacist rule and, perhaps more surprisingly, the economic sanctions that the United States and other Western countries imposed in hope of inducing South Africa to moderate its racial policies.

And part of his mission as embassy first secretary is to persuade as many Americans as possible that sanctions, however well-intentioned, have had a devastating effect on the well-being of countless South Africans--virtually all of them black.

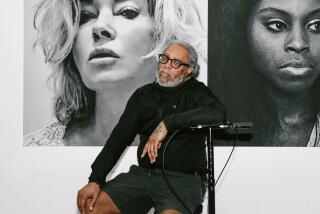

Jacobs, 53, reflected the other day on his migration from pedagogue to diplomat as he sat in his spacious office amid photographs of many of the white men dispatched here as ambassadors by various pro-apartheid governments over the years.

“I taught for 35 years. Fifteen of those I was headmaster of three different schools. It is very difficult to try to teach a child when that child comes to school hungry, when the child is not properly clothed, when the child’s family is not properly housed,” he said.

Jacobs said that as headmaster of the three schools much of his time was spent raising funds at factories and other firms to help his students and their families. He came to rely heavily on some of the American companies based in South Africa.

Then, in 1986, Congress overrode President Ronald Reagan’s veto of legislation to impose economic sanctions against South Africa. Although the sanctions did not require U.S. firms to pull out of South Africa, Jacobs said many did so anyway. His community-service efforts suffered.

Funds that Jacobs had been able to obtain to feed needy students, to train teachers or to provide higher education opportunities began to dry up. Rising unemployment left many families impoverished. The American firms, he said with an air of certainty, “should not have withdrawn.”

In frustration, Jacobs decided to try to find a way to take his case against sanctions to the American people. Two years ago, at age 51, he quit his career in education and became a trainee in the South African diplomatic service. With luck, he would be sent to Washington. He arrived last July accompanied by his wife and two of his seven children. The remaining five are all grown.

By coincidence, less than a month after his arrival, President Bush lifted the sanctions in response to liberalizing moves by De Klerk, including the freeing of political prisoners and the dismantling of some of the more onerous features of apartheid.

Jacobs’ boss is Ambassador Harry Schwarz, who shares his subordinate’s distaste both for apartheid and for sanctions. Jacobs has lobbied hard to end all curbs to U.S.-South African economic ties, talking with state legislators and others. He seems disappointed with the results thus far.

“The only state that has lifted sanctions since I’ve been here is Oregon. All the others are still saying it is premature,” he said.

Not long ago, the notion of Jacobs working hand in hand with the white man’s government sitting in Pretoria was preposterous. Apartheid, he said, is a “system that was wrong, evil, a system that was designed to almost incapacitate the abilities of blacks, designed to reduce blacks to servants and laborers, to keep a certain section of the population as the masters, totally anti-anything that is consistent with true human values.”

His anger was fueled by some nasty run-ins with the police as a youth. He was once beaten up by an officer because he refused to call him “boss.” He shook his head at the memory of that period. “Sometimes I felt it was a joyful pastime for police to beat up on blacks,” he said.

He flirted with the idea of becoming an anti-apartheid militant as a young man, pointing out that only menial jobs were available to blacks in those days. But his father died when Jacobs was 13, leaving him the male head of a large family.

The family recommended that he become a community activist instead of a political activist, and he bowed to their wishes. “That is where my sense of community involvement began,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.