A TALE FROM THE DARK SIDE : John Rinaldo’s Life as a White-Collar Criminal

Any doubts Paul Sarkozy had about investing his life savings--about $600,000 of the settlement from an auto accident that left him a paraplegic--with John Rinaldo vanished after the glib moneyman hosted a dinner party for Sarkozy at a splendid house in Newport Beach.

Set on a golf course behind security gates, the home dazzled Sarkozy, an Eastern European refugee unaccustomed to elegance. “I was impressed,” Sarkozy said. “He was a man of means.”

But what Sarkozy did not know about Rinaldo haunts him to this day.

Rinaldo was neither the banker nor lawyer whom he repeatedly claimed to be. Rather, he was a convicted felon, released from prison less than a year earlier. The impressive house belonged to Rinaldo’s first wife, from whom he was divorced in the mid-1970s; he used it without permission.

Instead of giving Sarkozy financial security, Rinaldo and another ex-convict named Nicholas Sterner ended up losing most of his money in high-risk stock-market investments, according to interviews and a lawsuit that Sarkozy has filed against the two men. Unable to work because of his injuries, Sarkozy today lives in southern Oregon on $340 a month in government assistance.

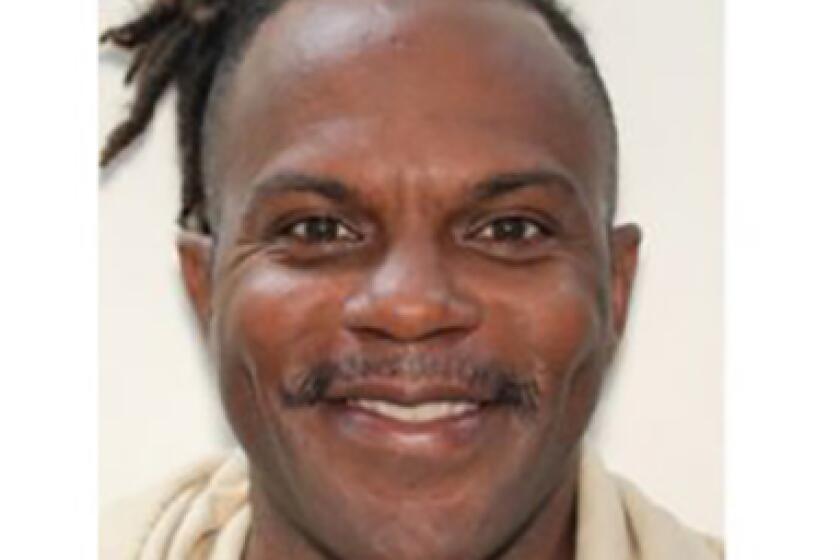

The life of John Gary Rinaldo--a middle-class kid from Long Beach who went on to personify the newly rich business elite in Orange County before sliding into crime 10 years ago--is a series of tales from the dark side.

Rinaldo has embarked on a career of white-collar crime and fraud that only accelerated as the years passed. Silver-tongued and shameless, he typifies the characters who have made Southern California a notorious center of white-collar crime.

At age 53, Rinaldo is back in prison for the second time, leading those once close to him to question what went so wrong. “He certainly did not start out that way,” said Gay Rinaldo, his first wife.

Rinaldo refused to be interviewed for this story.

At his zenith, Rinaldo ran one of California’s largest trust-deed investment firms, American Home Mortgage. As his wealth grew, so did his profile. He was politically connected and well-known in Orange County’s cultural and philanthropic circles.

Rinaldo pleaded guilty to mail fraud in 1985 after American Home failed amid extensive publicity. Investment losses, including missed interest payments to investors, ran in the tens of millions of dollars.

Though Rinaldo’s story is singular, his pattern of behavior is not. Many of those convicted of white-collar felonies never bounce back. Released from jail, they rarely are accepted back into respectable society, law enforcement officials say.

Indeed, Rinaldo was again convicted last May, this time for an attempt to obtain a $362,000 mortgage on a Newport Beach home that he did not own. At the time of his arrest, he was driving a red Mercedes that was reported stolen; an auto theft charge against Rinaldo was later dropped.

The loan fraud was a case study in criminal daring and imagination, with the Persian Gulf War as the backdrop. After minimal deliberation, a jury found Rinaldo guilty of five counts of bank fraud and money laundering.

Rinaldo received the minimum sentence--a 46-month jail term, not the 57-month maximum--because of his service as a key prosecution witness in a Mafia-inspired murder-for-hire case in the Midwest.

Rinaldo testified that the man who ordered an Indiana double murder confessed to the crime while the pair were in jail together in Los Angeles last year.

Otherwise, U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson said, Rinaldo would likely have gotten the maximum sentence for loan fraud. From the bench, Wilson called Rinaldo a “pathological cheat.” Rinaldo is now in the federal prison in Lompoc.

Rinaldo received his higher eduction at Long Beach State and USC after graduating from parochial school in Long Beach. An intellectual youth, he was a superb chess player who once played against eventual world champion Bobby Fischer in a U.S. Open chess championship.

He spent more than a decade as a small businessman, running a tax-preparation service in Long Beach and forming real estate limited partnerships before founding Newport Beach-based American Home Mortgage in 1977.

Riding the crest of a real estate boom, American Home Mortgage soon had thousands of investors from all over the state who put their pension funds in residential and commercial properties, earning rates as high as 18%.

As company founder and owner, Rinaldo was worth more than $7 million. He owned three homes in Newport Beach and a Rolls Royce, attended the opera in San Francisco and had gourmet meals at home prepared by personal chefs.

“His life was all champagne and caviar,” one former business associate said.

Yet, Rinaldo was a mercurial character even in good times. He was known to hold sales meetings at home while still dressed in his pajamas and was quick to anger in closed-door meetings.

As the California real estate market began to weaken in the early 1980s, his business began to crumble. Investors complained bitterly that they did not know why their interest payments suddenly had stopped.

In fact, American Home was caught in a downward spiral of borrower defaults and funding shortages. It failed to disclose key information to investors, and its operations were hampered by conflicts of interest, prosecutors charged.

Rinaldo clearly was ill-equipped to stanch the bleeding. In their 1985 pre-sentencing report, prosecutors described Rinaldo as an arrogant figure who had little use for detail and was inclined to “reckless business decisions.”

Though prosecutors pushed for a long prison term after Rinaldo pleaded guilty to mail fraud, U.S. District Judge Terry J. Hatter in Los Angeles meted out a three-year jail sentence.

“I do understand that you are at a crossroads,” the judge said at the sentencing hearing, “but I think you are a man of such significance, mentally and otherwise, that you will rebound from this and . . . do very well.”

Rinaldo has been going downhill ever since.

Rinaldo at first was sent to a minimum-security jail in Lompoc, but problems in jail caused his transfer to a medium-security prison on the Texas-New Mexico border. Broke and embittered, by some accounts, he was freed in late 1987, nearly a year after his original release date.

Alone, separated from his second wife, Rinaldo met and later married a third wife. And he hooked up with Sterner, whom he had met in prison and who was living in Los Angeles.

Through Sterner, Rinaldo eventually met Sarkozy, who was an auto mechanic. Both Sterner and Sarkozy were Eastern European refugees who shared a common language, Hungarian; they met playing soccer in Hollywood.

Sarkozy’s spine was broken after his disabled car was rear-ended by a truck on Interstate 10 near Blythe on Christmas Eve, 1983. Eventually, he turned to Sterner for investment advice. Though the pair were good friends, Sarkozy says he was not aware that Sterner had spent time in prison.

Paid a settlement of more than $1.3 million, Sarkozy initially invested the money in certificates of deposit and stocks, but he withdrew the money because he was uncomfortable with any kind of risk. An emotional man, Sarkozy by his own account had frequent quarrels with investment advisers and lawyers, who he believed were misleading him.

With little financial sophistication and a limited mastery of English, Sarkozy had great faith in Sterner and the ever-smooth Rinaldo. Sarkozy eventually turned over $806,000 in installments of $200,000 and $606,000; only a minor portion ever was returned, Sarkozy contends in court filings.

To Sarkozy, Rinaldo came across as an impressive attorney with an expansive vocabulary. He “acted like a big-shot lawyer,” Sarkozy said in a court deposition. Sarkozy said he did not know Rinaldo had a criminal record either.

Instead of putting the money into conservative real estate ventures, as Sarkozy said he wanted, Rinaldo and Sterner set up a partnership that invested--and lost--much of the money in high-risk stocks and options. Other funds simply were stolen, Sarkozy alleges in his lawsuit.

Sterner, through his attorney, denied the allegations and claimed to have been victimized himself by Rinaldo. Sterner and Rinaldo “were not partners in crime,” asserted the lawyer, David Katz, a former federal prosecutor in Los Angeles.

Rather, Sterner--like Sarkozy--believed that Rinaldo was a banker and attorney, according to Katz. Sterner also insisted that Sarkozy knew his money was being placed in high-risk securities. (Sterner is back in jail, convicted of conspiracy to sell stolen U.S. Treasury checks; he is awaiting a hearing later this month on his request for a new trial.)

Regardless of who was at fault, the investments were hardly appropriate for a person in Sarkozy’s position. Such trading should have been done only by a wealthy investor who could afford to lose everything, according to securities consultant Edward Horwitz, who examined Sarkozy’s dealings at the request of his Encino lawyer, George Baltaxe.

“They were taking positions that would either lose big or win big,” Horwitz said in a phone interview.

Sarkozy’s confusion was particularly apparent when he met with James Alexander, head of J. Alexander Securities in Los Angeles. More than $600,000 of Sarkozy’s money was invested through the small brokerage firm.

In his lawsuit and interviews, Sarkozy charged that the brokerage permitted the risky trading even though the firm knew he could ill afford it.

Alexander denies doing anything improper, saying that his firm had no responsibility for the trading losses because Sarkozy had given Rinaldo and Sterner a power of attorney to invest the money.

At 47, Sarkozy now lives on food stamps and disability payments in Medford, Ore., where he owns a home. His voice cracks when he talks of the money that was lost--funds that he had counted on to live the rest of his life.

“This is my life now,” he said, referring to his legal efforts to get his money back.

Sterner and Sarkozy both still believe that the home in Newport Beach that was the site of the impressive party belongs to Rinaldo. The house is actually is owned by Rinaldo’s first wife, real estate records show.

In a phone interview, Gay Rinaldo said that her ex-husband used the house without her permission while she was out of town over the Labor Day weekend in 1988. Gay Rinaldo said she returned home unexpectedly the morning after the party to find the house a mess and Rinaldo upstairs asleep.

“It was the only time that I know of that he used my house,” she said.

A certain chutzpah is certainly part of the Rinaldo style.

He would not vote for George Bush, he once declared, because the President “is such a crook.” Evicted from his luxury Marina del Rey apartment for non-payment of nearly $30,000 in rent, Rinaldo managed in court proceedings to make himself out as the victim. He complained that his possessions were not released quickly enough.

When a posse of law enforcement officials wanted to question him for possible credit card abuse, he managed to elude them. “We never did get to him,” Santa Monica police Detective Nancy Burum said. “We were always two or three steps behind.”

Law enforcement officials finally caught up to Rinaldo on Feb. 13, 1991--the day he was arrested in an FBI sting at the office of Sterling Home Loans in Santa Ana.

That story, according to court records and interviews, began after the launching of the air war in the Persian Gulf a month earlier, when Rinaldo contacted the loan brokerage, saying he wanted a mortgage on a vacant house in Newport Beach.

He identified himself as a lawyer named Lee Gerald Alpert and claimed to represent a Kuwaiti family that owned the million-dollar home. The Kuwaitis, he said, needed cash because their assets had been tied up by the war.

In fact, the home was--and still is--owned by three Iranian brothers: Amir, Amin and Fardin Mostafavi, the owners of an electronics company in the Silicon Valley. At the time, the house was for sale, but the “For Sale” sign kept disappearing for reasons the owners could not understand.

Rinaldo submitted a loan application to Sterling replete with counterfeit records, including phony tax returns for the Mostafavis, according to Donald Lyons, president of Sterling. Rinaldo even arranged to show an appraiser around the house.

Once the loan was approved and funded through a local bank, Rinaldo called a well-known gold dealer in Encino named Barry Stuppler, saying he wanted to convert nearly $300,000 of the loan proceeds into Canadian Maple Leaf gold coins.

Stuppler, though, alerted the FBI, because he felt “Alpert” was acting strangely.

“He did not ask about the price” of the gold, Stuppler explained in a phone interview. “He just asked when it could be delivered.”

After FBI agents confirmed that no attorney named Lee Gerald Alpert existed (though there is a lawyer named Lee K. Alpert in the San Fernando Valley), they arrested Rinaldo in a “sting” operation when he arrived at Sterling’s office to collect the gold.

“It was right out of Efrem Zimbalist,” Lyons said.

Rinaldo arrived at Sterling in a red Mercedes reported stolen 11 days earlier by David Palagyi, an Anaheim Hills financial consultant.

The thief had jumped in the car and driven away when Palagyi had left the vehicle momentarily unattended, federal prosecutors said in court filings.

According to Palagyi, the person who took his car had answered a newspaper for-sale advertisement. He claimed to be a pharmaceutical executive in the midst of a transfer to Southern California from Europe, Palagyi said in an interview.

Something about the bogus buyer vaguely reminded Palagyi of an Orange County businessman that he had met years before, when Palagyi worked for an Anaheim bank--a memory that proved accurate.

Said Palagyi: “I thought, ‘That guy reminds me of John Rinaldo.’ ”

ANATOMY OF A FRAUD

Jan. 17 to Feb. 13, 1991

1. John Rinaldo, posing as an attorney named Lee Gerald Alpert, calls Sterling Home Loans in Santa Ana, saying he wants a $362,000 mortgage on a house in Newport Beach. He says he represents a Kuwaiti family whose assets are tied up by the Persian Gulf War.

2. Sterling Home Loans appraises the vacant property at $1.1. million.

3. Rinaldo submits a phony loan application and escrow instructions directing that nearly $300,000 of the money be paid to him in gold coins.

4. Rinaldo allegedly steals a red Mercedes in Anaheim Hills.

5. Sterling Home Loans funds the loan through Mission Viejo National Bank.

6. Rinaldo arrives at the loan office in the Mercedes expecting to pick up the gold coins. Instead, he is arrested by FBI agents. The box supposedly containing his gold instead is filled with lead--and a sheet of paper saying, “Boo.”

7. Rinaldo receives a 46-month prison term for money laundering and bank fraud. He is serving his time in a federal prison in Lompoc.

Sources: Federal court records, interviews

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.