Jazz Saxman Carter, at 84, Hasn’t Slowed Up Much

SAN DIEGO — You expect a list of a jazz legend’s recordings and compositions to run several pages. But alto saxophonist Benny Carter’s list is so long, his biographers gave it a whole book--the second volume of the 1982 “Benny Carter, A Life in American Music.”

Since the 1930s, Carter has been regarded by critics and fans as one of a handful of primo alto saxophonists, including Charlie Parker and Johnny Hodges.

Carter has outlived them all. He launched his professional career while still a teen-ager and, by 1928, at the age of 21, had formed his first Big Band. He has maintained a tireless pace since and, at 84, has barely slowed down.

Friday through Sunday nights, Carter performs at the Jazz Note in Pacific Beach. Next month, the Hollywood Hills resident will tour Japan with his Big Band. During the spring and summer months, he will play jazz festivals, both in the United States and abroad. And, in the fall, a recording will be released of two original suites Carter composed for a Big Band to play with a classical symphony orchestra.

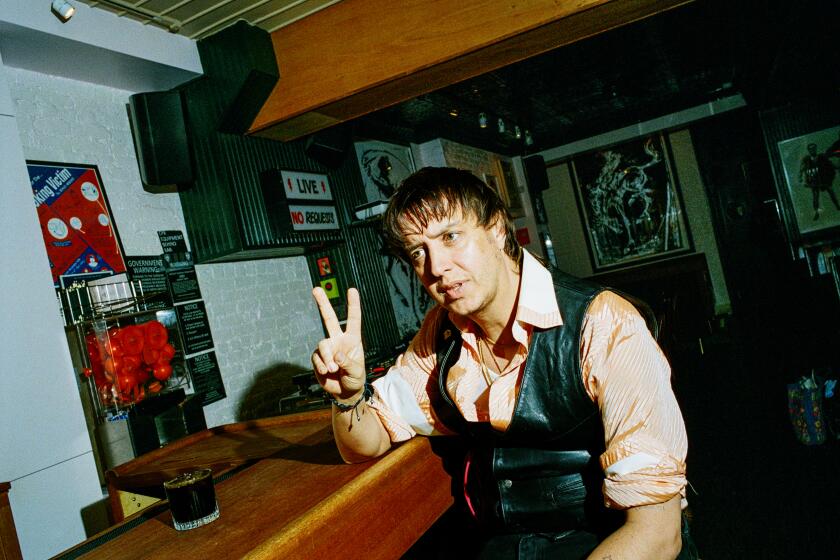

During an interview, Carter is extremely polite and friendly, but he is also intensely private, not given to blowing any horns of his own, other than his saxophone and, occasionally, his trumpet. He has never felt compelled to analyze or explain his music, regardless of how questions are posed.

How has his playing changed over the years?

“I leave that to the listener.”

Does he feel his playing has matured,

become more technically accomplished?

“I don’t think so, but if someone does I won’t dispute it.”

Does he have a personal favorite among his hundreds of recordings?

“No.”

What does he believe his contribution has been to the evolution of the alto sax?

“I won’t say, but I’m happy if someone else does,” he said recently.

Saxophonist James Moody, an internationally known player who lives in San Diego, didn’t hesitate to sing Carter’s praises.

“He’s a fantastic man, besides being a fantastic musician,” Moody said. “The first time I ever saw Benny was when I was in the Air Force. In 1944, he came to Greensboro, N.C., with his band, I never will forget that. Benny was playing alto and trumpet. I think Max Roach was the drummer. It was a helluva band, Benny always had good musicians.”

Moody compared Carter’s musicianship with the skills of a smooth conversationalist who expresses thoughts in elegant, full sentences.

“One person might say ‘Family? Wife? Children?.’ Benny would say, ‘Your Mrs., how is she today?,”’ Moody explained. “He plays the (chord) changes, believe me. And he connects them the way they should be connected.”

His most recent recording shows his work is as vital as ever. He is equally adept at providing the juice for electrifying, up-tempo tunes and wringing maximum emotion from slow, romantic ballads.

His 1990 pairing with fellow alto saxophonist Phil Woods, “My Man Benny, My Man Phil,” bristles with lively exchanges between the two players. On his newest release, last year’s “All That Jazz Live at Princeton,” Carter and trumpet/fluegelhorn player Clark Terry team up to run down some fast melodies in tight counterpoint. Carter also turns in some glistening solos, delivering warm, lyrical inventions with a warm, inviting tone.

Not bad for a guy who claims he practices “very little.”

But Carter has always been as interested in composing and arranging as playing, and, at the moment, he has been busy writing. When he takes his Big Band on the road next month, they won’t be on a nostalgia trip. Carter is writing a batch of new material.

Carter is an encyclopedia of history, and not just about jazz. He lived in New York City during the 1920s and 1930s, and was well aware of the Harlem Renaissance, the blossoming of black writers, artists and musicians in Harlem. For his recent Big Band-symphony orchestra recording, Carter dipped into the past to tap the energy of that era. The recording consists of two suites: “Tales of the Rising Sun,” Carter’s tribute to Japan; and “Harlem Renaissance,” his musical homage to that lively period of African-American creativity.

Carter said he did not know most of the Harlem Renaissance artists personally, but writer Langston Hughes left an impression. Carter was interested in capturing the general mood of the times in his “Harlem” suite, but he devoted a whole movement to Hughes, titled “Lament for Langston.”

Carter hopes to perform these original Big Band-symphonic works in Southern California sometime in the not-too-distant future, he said.

He also said he is “thinking seriously” about recording with some top young players on the jazz scene, but wouldn’t name names.

“There are too many,” he said, giving a brief, but positive, assessment of the current state of jazz.

Carter was born and raised in New York City. He broke into Big Bands by playing with, as well as composing and arranging for, the top Big Bands of his day. Althoug Benny Goodman is often credited with launching the Swing Era, Carter supplied some of the arrangements that made Goodman’s band popular.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Carter led several Big Bands of his own. Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach were among the young players who came up through Carter’s band.

For three years during the 1930s, Carter lived in Europe, where he left his mark on flourishin jazz scenes in Paris, London and Holland. He played with Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli at the famous Hot Club of France. Enthusiastic European jazz journalists documented Carter’s every move, heaping praise on his playing and composing skills.

In California during the late 1940s and 1950s, Carter carved out a second career for himself in movies, writing, arranging and playing music for dozens of films, including “Stormy Weather,” “The Sun Also Rises” and “An American in Paris.”

He continued recording and touring right through the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s, while he also committed his time increasingly to education, teaching at Princeton and other universities.

Carter received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987, an ironic accolade for a man who has never been awarded Grammys for his dozens of albums and film scores.

“I think jazz has suffered a great neglect,” Carter said in a rare opinionated moment, acknowledging how the Grammys generally ignore jazz. “But rock ‘n’ roll sells records, and the record people are in the business to make money.”

As for his prolific career, Carter would provide no insights into his longevity.

“I can’t think of any,” he said. “Fifty-eight pushups a morning? I tried that once. I couldn’t get beyond two.”

Carter’s Jazz Note shows begin at 8 and 10 Friday and Saturday nights, 7 and 9 on Sunday night. He will be joined by pianist Larry Nash, bassist Marshall Hawkins and drummer Larance Marable.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.