Wrapped in History and Beauty : The colorful and sensuous sari remains the preferred attire of many Indian women. An exhibit of the garments will open at CSUN.

- Share via

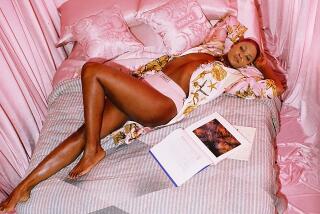

Their gorgeous colors inspire sudden sensations of joy and awe. The textures and designs of their handwoven, pure silk or cotton material, often trimmed in gold brocade, intensify their sensuous nature.

They are the saris of India--the traditional dress of Indian women--which historians believe existed in some form as far back as 1500 to 500 BC. Today, while most Indian men have donned Western-style clothes for everyday use, most Indian women continue to wear saris daily. Gracefully pleated and wrapped around a woman’s figure, the sari envelops her in beauty, and in Indian history and custom, and Hindu ideals of feminine beauty.

“I love wearing a sari because for me it’s the most sensual, luxurious feeling. I love the quality and the energy that goes into making it,” said Annapurna Weber, 26. She has organized “Saris of India,” an exhibit of 25 saris on view beginning Monday at Cal State Northridge’s Art Galleries that spotlights the beauty of this garment.

A CSUN graduate with a degree in art history, Weber is a doctoral candidate at Columbia University in New York. Born in India, she came to the United States with her mother in 1975 at the age of 8. They joined her father, an engineer, who had located in New Jersey the year before. When she was 15, she returned to India to study for three years.

There, she was also aware of how traditional dress was used as “a way for some of my family members to control me, by putting me back into a context in which they could deal with me,” she said. “If I wore jeans or pants, I would be stepping into the aspect of the Western ‘other,’ and into male territory, and it’s easier to deal with me if I’m not in that territory. I clearly saw that, but on the other hand, it didn’t interfere with my enjoyment of the sari.”

Her most vivid childhood memory is of her mother taking off her sari after they would come home from an occasion. She remembers the sari “laying on the floor in a pile, and me just dropping on it and luxuriating in it,” she said. “Even now, my mom tells me I frequently fell asleep on the sari that way. I definitely think that had a lot to do with my interest in it.

“I have always been interested in fashion, how fashion defines gender and how people who are not Indian read Indian women in their native clothing,” she said. “There is a real tendency to put them into those roles of the agreeable, pleasant, subservient woman. And that’s not true. I don’t think that the costume necessarily speaks to that.”

“The sari is part of a whole spectrum of Indian art,” said Louise Lewis, CSUN’s gallery director. “I knew a sari show would be exquisite, and the whole idea of the fluid quality of a sari would make for a very different show.”

The eclectic group on display comes from a collection of about 90 saris gathered by Weber’s mother, Vijayalaxmi Garimella. She lives in Ventura and works for the county as a computer graphics specialist. Most of these saris date from the 1980s, with a few from the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“She is a collector in the truest sense of the word because she used to have a lot more, and then she weeded out marginal pieces by giving them away, and really consolidating,” Weber said. “She’s not buying as much, but the few pieces that she buys are very, very nice.”

And she continues to wear them.

“When I have Indians around me, if I wear Western clothes, I feel odd,” Garimella, 43, said. “I feel that I am not wearing the proper clothes. When we get together, all the Indians, we only wear saris.”

A majestic yellow-gold and maroon silk sari from Kanchipuram, which is in the show, was worn by her to Annapurna’s wedding to Mark Weber.

“We in India use really bright colors--red, green, yellow, maroon,” she said. “When you wear a particular color, you get the auspicious mood. If I wear red and yellow, I feel I’m about to do something really special, go to a celebration or something.”

Red and white is one of her favorite color combinations. However, she called the vibrant, rich green silk sari with red dots from Arani her favorite.

“When I wear this sari, I feel pretty, I feel happy,” she said.

Weber said she can determine which area of India a sari comes from by the type of material, the weaving technique, the dying, the type of design on it, and sometimes by the color.

“You can be pretty sure if you see mirror work, it’s going to come from Rajasthan,” she said. “Or if you see a bandhini print which is tie-dyed, that it also comes from Rajasthan or is Sindhi-influenced tie-dyeing. The body and the border always contrast in saris from Kanchipuram.”

One aspect of a sari that remains almost universal is its size. Today, most of them are 5 1/2 to 6 yards long and 45 inches high, although some are 7 yards long. Tucked pleats at the waist are imperative to wearing the sari properly. In the past, women usually tucked them in the back, which requires the longer cloth. Today, front tuck pleats are the norm. Otherwise, there is almost no variation among women in the way they wrap their saris.

The blouse and petticoat that complete the standard sari for most Indian women today became part of the dress code after the British came to rule India in 1858.

“In the past, the finer and more diaphanous the sari, the more valuable it was. The British disapproved of this sari style: For them, the sheerness was too titillating and thus immoral,” Weber said in a show catalogue essay. “It appears that the petticoat worn under the sari came into place to deflect the intense criticism made by British missionaries about the immodesty of the Indian woman’s clothing. During the same time . . . the blouse or bodice . . . became a fixed upper garment for most Indian women.”

Few saris exist from the past because custom dictates that women recycle them. When frayed, they are cut up and sown into pillowcases, redyed, exchanged for household items or given to servants.

“If they are cotton saris and we think they are not wearable any more, we fold them into maybe four folds, and add a number of saris together, and make it like a quilt,” Garimella said. “They’re colorful, soft and comfortable.

“The saris in India are for daily use. They are not any fancy collectors’ items, even the most pure silk saris. They are not kept as heirlooms or art objects.”

As a result, documentation on the historical and cultural significance of saris is scarce.

“A lot of the motifs that keep showing up on saris are found on temple walls,” Weber said. “A border of ducks often appears on saris. Well, ducks on temples mean auspiciousness. Ducks and rabbits are associated with fertility and fertility leads to auspiciousness. If you speak to people who wear saris in India now, they will say that this is what they represent. There may have been more than that, but it’s certainly gotten lost along the way.”

Weber also thinks costume history has been relegated to the lower echelons of suitable art history topics because “it’s an art form that can’t be taken away from the average person,” she said. “To me, dress is how in a modern secular world we’ve incorporated art into our daily lives.”

Weber said she has integrated the sari into her life at Columbia. When she does wear one, non-Indian people can be quick to give it some spiritual or religious meaning.

“It’s like the Dalai Lama’s robe or something,” she said with a laugh. There is also another reaction, which is that Indian women are hidebound by tradition and they can’t really get out of it--because of that, they’re stuck wearing this clothing, or even after they come here, they can’t leave their old culture behind.

“Saris are really interesting because they are such a symbol of femininity in a time when things are changing so rapidly in India. Gender issues related to clothing are being hashed out. For me, they remain this wonderful, sensual material even though there’s a lot of history of trying to lock women into subordinate positions with them.

“I’ve always had a clear sense of where I stood with my identity as far as clothing was concerned. I don’t reject the sari just because it has all these connotations for some other people. For me, the object is one thing, the baggage is another.”

WHERE AND WHEN

Exhibit: “Saris of India.”

Location: Cal State Northridge’s Art Galleries, 18111 Nordhoff St., Northridge.

Hours: Noon to 4 p.m. Monday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays, through Nov. 21.

Opening program: Annapurna Weber will lecture on the “Saris of India” at 10 a.m. Monday. Harihar Rao will present “Music of India” at 2 p.m. The exhibit’s opening reception is from 7 to 9 p.m.

Call: (818) 885-2226. Group tours available by appointment, call (818) 885-2156.