COLUMN ONE : Economies Ache All Over Globe : Each nation’s malaise is compounded by the others’. Lack of leadership is a problem. No country is stepping forward to haul the rest of the industrial world out of the gloom.

To paraphrase Tolstoy, all healthy economies are alike, but every unhealthy economy is miserable in its own particular way. And right now just about all the world’s major industrial economies, from the United States to Europe to Japan, are in their own special kind of funk.

All are scratching to restore some semblance of economic vigor. For the moment, though, all are dragging each other down. The odds of full-scale recovery in the United States now depend heavily on the prospects of weakened, floundering economies around the globe.

Britain is mired in a full-fledged recession as it tries to kick the hangover from a cheap-credit boom in the 1980s.

Germany, under the financial pressure of reunification, has lapsed into what even Chancellor Helmut Kohl concedes is a recession. With French unemployment exceeding 10% and Italy desperately trying to control a runaway budget deficit, those two countries may not be far behind.

Continuing chaos on Europe’s currency markets, climaxed by devaluations of the British pound and the Italian lira in September, has damaged investors’ confidence throughout the Continent. Adding to the uncertainty is Europe’s agonizing, inconclusive move toward a single currency and closer political union.

Japan is faced with plunging values of land, stock and other assets. Productivity growth has declined, and the pace of economic growth has fallen by two-thirds.

As for the United States, the economy grew at a surprisingly high annual rate of 3.9% in the three months from July to September, but nobody believes that pace is sustainable. There may be no more telling indicator than a forecast this month by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The chamber predicted that the economy would keep growing for the rest of this year, but only because of massive spending to rebuild areas of Florida and Louisiana devastated by Hurricane Andrew. Then, the chamber said, the economy will slip back into its coma, with no reduction in the stubborn 7.5% unemployment rate.

Each nation is suffering because of the others’ illnesses. Germany has exported its high interest rates to most of industrial Europe. U.S. sales overseas, which continued rising even during the recession, have tailed off because of weak demand in foreign markets. Japan’s trade surplus is mounting again to an estimated $120 billion this year--enough, according to MIT economist Lester Thurow, to cost the rest of the advanced industrial world 3 million jobs.

Hardly anyone predicts a downward spiral into a global depression, 1930s-style. The world has learned to reject the policies of tight money and tough trade barriers that ushered in the Great Depression. Another good sign: Developing countries of the Third World, especially in Asia, are thriving.

But neither does anyone think that the world’s industrial powerhouses are going to get much healthier anytime soon.

“The global economy continues to navigate narrowly between recession and recovery,” said Brian Mullaney, a London-based economist for the investment house Morgan Stanley International. “And while the risk of worldwide recession remains very low in the year ahead, we believe that meaningful economic recovery will be delayed beyond 1993.”

A big problem is the lack of leadership. No country is stepping forward to haul the rest of the industrial world out of the gloom. The United States played that role in the 1980s, and Germany at least buoyed up most of Europe in 1990 and 1991. But now even Japan is growing more sluggishly than at any time since 1974.

What’s more, political leadership worldwide seems weak and ineffectual, and governments lack mandates to institute bold economic rescue programs. Economic woes helped drive President Bush out of office; elsewhere in the industrial world, political scandals are compounding incumbents’ misery.

Japan’s government is beset by another in a seemingly endless series of scandals over political bribery. An influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe has triggered reactionary protests in Germany. Britain’s government is fighting charges that it secretly helped arm Iraq before the 1991 Persian Gulf War.

“In many of our countries, governments--in fact, the entire political class--no longer seem to have adequate backing of the population,” said Jean-Claude Paye, secretary general of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, whose members are the world’s 24 most industrialized nations.

Meantime, only a U.S. threat to slap punitive tariffs on European Community imports has finally broken a two-year deadlock and rekindled hopes for a new international agreement to liberalize world trade. The sorry economic shape of the former Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites contributes to anxieties everywhere.

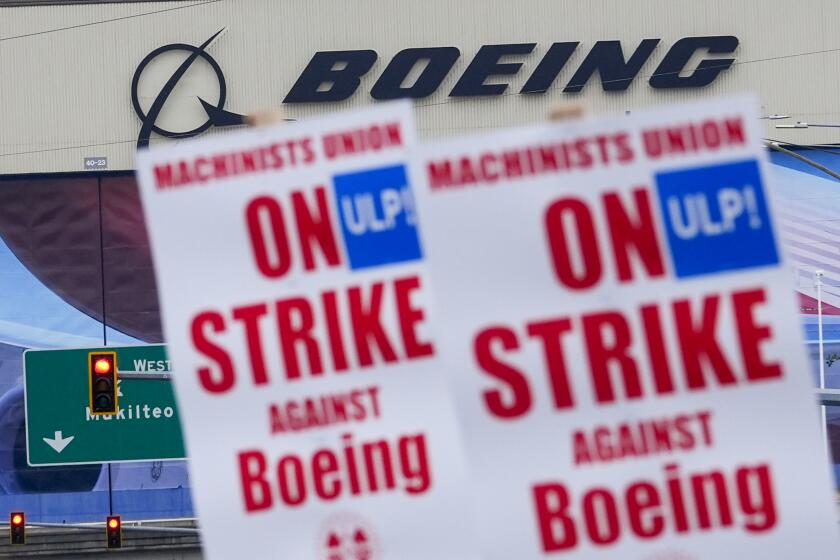

All of this is bad news for American companies that depend on exports. At Boeing, the nation’s single largest exporter, for example, aircraft orders plummeted from nearly 700 a year in 1988, 1989 and 1990 to about 170 this year. While the sales picture remains relatively bright in Asia, Boeing is hurting in North America, South America and Europe.

Such foreign pressures come on top of others at home. Like hundreds of other firms, Boeing has felt the bite of large reductions in U.S. military spending. The firm has cut its payroll by 9,500 jobs this year, to 144,000 full-time workers, largely because of cancellations of Pentagon orders for such hardware as missiles, the Navy’s P-3 surveillance plane and the B-2 bomber.

No country has better reason to curse its fate than France. The Socialist government of President Francois Mitterrand, confronted by the disastrous consequences of its earlier policy of nationalizing major industries, did an about-face in 1983 and went on an austerity campaign--small budget deficits and tight money--designed to instill investor confidence in the French economy.

The policies worked. France now boasts the lowest inflation rate among the world’s major economies. Its currency is strong. Among big industrial powers, its budget is in better shape than all but Japan’s.

By all rights, France should now be reaping the rewards of winning international investor confidence in its ability to manage its economy. Instead, its economy is barely growing, and unemployment is 10.3% and rising.

The principal culprit is Germany, whose central bank has held interest rates high--around 9% now for short-term loans, compared with 3% in the United States. That has forced France to do the same in order to protect the value of the French franc against the German mark. Now those high rates are choking off economic activity.

Just ask Accor, a Paris-based company that owns chains of hotels and restaurants, mostly in France but including Motel 6 in the United States. Accor executive Eliane Rouyer said France’s high rates have curtailed the company’s expansion plans in its home market, even as much lower U.S. rates have permitted Motel 6 to grow.

“A new hotel is highly capital-intensive,” Rouyer said. “Under the best of circumstances, it takes an average of three or four years from the opening before a hotel can recoup its expenses and start turning a profit. When the cost of borrowing is high, it can take even longer.”

If it’s any consolation to France’s 2.5 million unemployed, Germany is also suffering. What is happening there echoes the U.S. experience of 10 years ago: Because the German government has let its budget deficit climb to unprecedented heights, the central bank has kept interest rates high to prevent an overheated economy from generating too much inflation.

In Germany’s case, it was the need to pump huge sums into the east after reunification that threw the budget out of kilter. Now the reunification boom of 1990 and 1991 is fast petering out, but the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, has scarcely begun to loosen its iron grip on rates.

“Expectations for the coming year are stamped with insecurity,” the German Chambers of Commerce and Industry reported this month after surveying 25,000 enterprises.

The survey found that 32% of the businesses expect to trim their work force next year, compared with only 9% planning to grow.

Thyssen, the big German steel maker, is typical. It is having a good year but expects sales to be flat and profits to be down in 1993. High interest rates are not only driving Thyssen’s costs up but also inflating the value of the deutschemark against the dollar and the British pound, and that is making it difficult for Thyssen to compete in price with American and British manufacturers.

Overall business investment in western Germany is declining for the first time in a decade. And although investment is continuing to increase in eastern Germany in spite of recent decisions by Daimler-Benz and Krupp to drop plans for major expansions there, enterprises in the east are failing faster than new ones are opening.

Consequently, many eastern Germans are out of work for the first time. Regina Golle, 53, had worked for 21 years as a secretary at a government-owned women’s wear manufacturer in East Berlin before the plant was closed for want of a private investor willing to buy it.

“Thank God my husband earned money at that time, so that I didn’t fully lose my footing,” Golle said. “A former colleague of mine, single with two children, committed suicide.”

Even those still working are fearful of the future. “People here are just afraid that foreigners will take their jobs and their social welfare,” said Rolf Dippel, a toolmaker with Ringsdorff, a metal-products company in Bonn.

At least Germans haven’t gone through what Britain has endured: more than two years of recession, with an unemployment rate now at 10.1%.

“I don’t see any end to this recession, not unless the government drastically changes its policies,” said Harriet Hooke, a 48-year-old London accountant laid off six months ago.

Waiting in line at a run-down unemployment office, with a chill wind blowing through broken windows, Hooke said: “The recession has been worse in this country and lasted much longer than elsewhere. They just can’t keep on blaming the rest of the world.”

The outlook in Britain actually is darkening. A survey of 1,308 British companies last month found 35% more pessimistic about the future than they had been four months earlier, and only 12% more optimistic. For every company that plans to increase investment in the next year, four companies plan reductions.

Britain’s construction industry has been particularly hard hit. Tarmac, a major home builder and contractor on the much-delayed tunnel under the English Channel, reduced its work force this year to 28,000 from 32,000 and was forced to sell subsidiaries in California and Texas to raise money to pay off debt.

“I see no real change in the fundamentals which have created the exceedingly poor conditions which prevail in our (British) markets,” said Tarmac chief executive Neville Simms.

The other principal victim of Europe’s September currency crisis was the Italian lira, reflecting the potential disaster facing the Italian economy.

Italy’s budget deficit is more than twice as great as the U.S. deficit relative to the size of its economy, and the government has proposed Draconian spending cuts and unpopular tax increases just to keep it from growing still larger. Employees, small business owners and professionals held protest marches across Italy last month, threatening not to pay proposed new taxes unless higher-paid managers also had to pay more.

Profits are plunging at Italy’s success stories of five years ago: Fiat (automobiles), Olivetti (office equipment), Pirelli (tires). With an economist’s understatement, Nigel Gault, of the forecasting firm DRI-McGraw Hill, predicted, “Italy faces several very tough years.”

Nor is the Japanese economy, the world’s second largest, doing the rest of the globe much good. Even as imports are shrinking, Japanese corporations continue to push aggressively into new export markets. Japan is growing at a limp annual rate of about 1.5%, with all of that growth coming from exports.

The slowdown in Japan began with a deliberate effort by the government to deflate soaring land and real estate prices. Beginning in late 1989, the government raised interest rates and restricted bank lending for real estate projects.

Stock and land prices plunged and are now down more than 50% from their 1989 highs. As consumers’ confidence waned, a five-year spending spree came to a halt. “Consumers have bought all the cars and refrigerators they are going to need for a while,” said Jesper Koll, Tokyo economist of the S. G. Warburg brokerage. “The Japanese consumer and corporate sector are now paying for their past consumption.”

Computer makers such as Fujitsu, auto makers such as Nissan and consumer electronics companies such as Sony are cutting back sharply on investment after spending heavily on new factories and automation equipment over half a decade.

To a chorus of protests, NEC Corp. is asking its employees to accept television sets and videocassette recorders in place of normal cash bonuses.

The drop in asset prices has left banks with hundreds of billions of dollars in bad debts. To shore up their reserves, banks and insurance companies are pulling back money invested overseas.

Unlike most other major industrial countries, which are hamstrung by huge budget deficits, Japan at least has been able to inaugurate government spending programs to try to pump up its economy. Parliamentary approval has been delayed by Japan’s political scandals, though. And Japan’s new public works programs will mean more business mostly for its own construction firms; foreign firms have scarcely cracked the Japanese construction market.

Europe is also looking at public works spending; Jacques Delors, president of the EC’s executive commission, is talking about a program as big as $75 billion. However, the fine print shows that all but a tiny fraction of that money would be not new but merely reprogrammed from national EC budgets. “This is not the time for deficit-financed economic programs,” said Horst Koehler, Germany’s secretary of state for finance.

Now it is the U.S. government’s turn to try priming its economic pump. While President-elect Bill Clinton promises to seek new spending for highway construction and other public works projects, many analysts doubt that this will be enough to bring the world’s biggest economy out of its coma.

“These jobs have a limited life span, even if there is a decade’s worth of projects that need to be built,” said David Wyss, of DRI-McGraw Hill’s headquarters in Cambridge, Mass.

Meantime, like so many workers in other nations, Joyce Stevens of Omaha, a state welfare department worker and divorced mother of three teen-agers, worries about her future.

Nebraska’s large budget deficit threatens to eliminate her job or force a cut in her $23,000 annual salary. “The only purchases I make now are in cash--but I haven’t made any major purchases over the last two years,” she said.

Stevens expects that whatever medicine Clinton prescribes for the national economy will hurt struggling workers and parents, including herself.

“I realize there’s going to be a lot of cuts to get the deficit down,” she said. “I’m sure it will affect me. If it doesn’t catch up with me one way--like higher taxes--it’ll get me in higher interest rates. Both will go up. I don’t think there’s any way around that.”

But she added, in a comment echoed worldwide: “Our country is due for an overhaul.”

Also contributing to this article were Times staff writers John M. Broder in Washington and Leslie Helm in Tokyo and researchers Petra Falkenberg in Berlin, Reane Oppl in Bonn, Fleur Melville in London and Janet Stobart in Rome.

Global Powerhouses in the Doldrums

Many of the big industrial nations are paying for excesses of the 1980s, when huge government and private borrowing and inflated property values fueled unsustainable growth. Here is economic growth in the seven largest industrial countries:

1991 1992 1993* United States -1.2% +1.8% +2.4% Japan +4.4 +1.5 +2.3 Germany +3.6 +1.1 +0.8 France +1.2 +1.8 +1.6 Italy +1.4 +1.2 +0.8 Britain -2.2 -0.6 +1.6 Canada -1.7 +1.4 +2.1

A Gloomy Forecast

The developing countries of the Third World, especially in Asia, are the only economic tier that is thriving:

1991 1992 1993* Industrial countries +0.6% +1.7% +2.9% Former Communist countries -9.7 -16.8 -4.5 Third World +3.2 +6.2 +6.2

* Projected Sources: International Monetary Fund, Morgan Stanley International

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.