Hepatitis Vaccines Promise Lifelong Protection : Other drugs in development are expected to protect travelers against cholera and encephalitis.

- Share via

New vaccines--some expected on the market soon and others in the pipeline--promise improved protection against hepatitis A, cholera and other diseases that can endanger travelers.

Two vaccines against hepatitis A, both developed by U.S. companies but not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration, offer hope for a lifetime of immunity and, on the lower end of expectation, are being touted by their manufacturers as at least 97% effective. Until they are approved, travelers trying to avoid hepatitis A must take immune globulin injections, which only offer immunity for about five months.

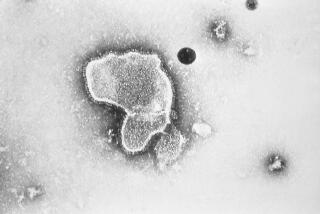

One of five known variants of hepatitis, hepatitis A (the form travelers are most likely to encounter) is marked by liver inflammation. Symptoms include swelling, fatigue, fever, muscle and joint aches. The disease is transmitted by contaminated water, ice or shellfish or other foods such as fresh fruit and vegetables cooked in sewage contaminated water.

Havrix, the new hepatitis A vaccine developed by SmithKline Beecham, is awaiting approval by the FDA, according to company spokeswoman Sharyn Arnold. In clinical studies, Havrix was 97% effective, she said. The vaccine is made by growing hepatitis A virus in culture, harvesting it and killing the virus before injection. The vaccine stimulates the body’s defense mechanisms, as a natural infection would, but without causing infection and disease. Havrix requires two injections and takes effect in about a month.

Another hepatitis A vaccine, Vaqta has been developed by Merck & Co. and has proved quite efficient. In a study of the vaccine, reported earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, it was so effective in all of the 519 children who received it that researchers halted the trial and vaccinated those who had been given placebos. Merck plans to file for FDA approval soon, a spokeswoman said, and may market Vaqta by 1994, pending government approval. The vaccine is made from an inactivated virus. It probably will require one injection.

The new hepatitis A vaccines, experts say, are superior to the currently available immune globulin injections. “Immune globulin is passive protection that probably lasts four or five months,” said Dr. Frank Mahoney, a medical epidemiologist at the federal Centers for Disease Control. When available, the new vaccines should be considered for use by travelers en route to developing countries or Mexico, especially those visiting rural areas, Mahoney said.

Earlier this month, the FDA granted approval to market a new vaccine against Japanese encephalitis, a mosquito-borne disease that strikes most often in the summer and autumn, according to the CDC. Called JE-VAX, it requires three injections over a month’s time, said Linda Mayer, spokeswoman for the manufacturer, Connaught Laboratories. The Japanese encephalitis virus is found in Japan, Korea, Vietnam and northern tropical zones such as Nepal, China, Vietnam and Thailand. Most infections cause no symptoms, according to the CDC, but the disease can be life threatening.

In clinical trials, JE-VAX vaccine proved 91% effective. The vaccine is expected to be available by mid-February, Mayer said, and will be recommended for certain travelers to Asia, particularly those spending a month or more in areas where the virus is prevalent or those who will spend substantial amounts of time outdoors in rural areas.

A better cholera vaccine might also soon be available. The current cholera vaccine, which is administered by injection, is not considered particularly useful (less than 50% effective) against El Tor--the most common kind of cholera--and as such, is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control. The new vaccine is slightly more effective (60%) and has the added benefit that it can be taken orally, said Dr. Robert Edelman, professor of medicine and associate director for clinical research of the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, who helped develop it. The last phase of human clinical trials of the vaccine is scheduled for early 1993 in Indonesia, he said.

Cholera is caused by an infection of the intestine by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Generally, cholera is contracted by consuming contaminated food, water or drink. Some who become infected don’t even suffer symptoms; others notice painless diarrhea without cramps or fever. But some experience severe effects of the disease, which can be marked by watery diarrhea, vomiting and leg cramps. Without prompt medical attention, cholera can kill by dehydration in as few as two hours, experts say.

The new vaccine, known as CVD 103-HgR, takes effect within about eight days, Edelman said. It works in part by preventing the toxin that causes cholera from adhering to the bowel wall. A Swiss institute is preparing to license the cholera vaccine there, Edelman said, and his research center will ask the FDA in January to grant approval to market the vaccine here without a U.S. field trial.

To protect against malaria, a new vaccine is also under study but is not expected to be widely available until 1998. It could replace the series of pills that travelers now take to avoid malaria, which attacks the liver and red blood cells and can be fatal.

Yet as promising as these new vaccines sound, travelers still need to be careful about what they eat and drink, advised Dr. Victor Kovner, a Studio City travel medicine specialist. Taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites can help, too.