The Scene : Apollonian Nights : The Harlem theater has been reorganized and amateur night revamped, but if the audience turns on you, you’re still in trouble

Twenty-five-year-old Belinda Butcher was only two bars into Anita Baker’s “Been So Long” when boos started to rumble from the audience on a recent amateur night at Harlem’s famed Apollo Theatre. The singer defiantly pressed on, letting loose with a powerful voice tempered by church choir training. Suddenly, cheers began to drown out the hoots and after a tug of war between boosters and boo-ers, Butcher walked off the stage with an expression of prayerful relief.

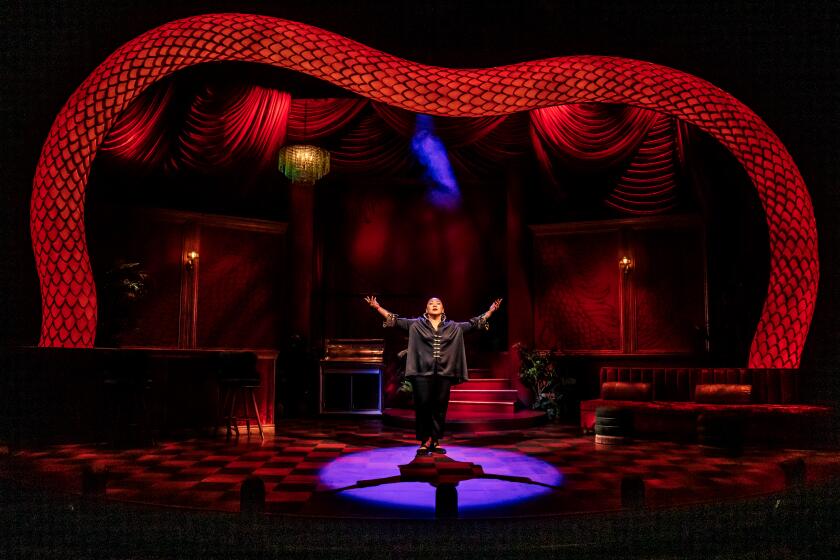

They’re calling it “The New Amateur Night at the Apollo”--a revamping of the show to go along with the theater’s new not-for-profit status, which may be its last chance for survival. But there was something brutally familiar about the audience that gathered here on the last Wednesday in January, and it wasn’t just the conservatively fashionable threads of the young African-Americans who occupied many of the seats in the half-filled 1,460-seat theater. Or the cabaret feeling induced by being allowed to sip cocktails from your seat after purchasing them at the bar at the back of the theater.

As has been the case for the last 59 years (to the day), the Apollo regulars were insisting on the right to anoint--or humiliate--those brave enough to endure what producer Deborah J. McDuffie calls “the trial of fire.”

“The audience is crucial,” said McDuffie of those attending what is probably the most famous talent showcase in the world. “The whole mood of fun and spontaneity stems from them. God help you if they turn on you.”

McDuffie was brought in recently to overhaul amateur night after the death last August of Ralph Cooper, the legendary Harlem showman who created and hosted the program since its inception. Since 1934, the show has been the cornerstone of the Apollo, helping launch the careers of such performers as Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Dionne Warwick, Sammy Davis Jr., the Jackson 5 and Luther Vandross. Indeed, the show is such a cultural institution that in the musical, “Dreamgirls,” the title characters get their first leg up on stardom by winning the Apollo Amateur Night competition.

Despite its legend, however, the Apollo has spent the last couple of decades fending off bankruptcy. Founded in 1915 as one of the few showcases for African-American talent, the theater closed in 1977. In 1983, a group of investors reopened the Apollo, but because of ballooning budgets, last month a not-for-profit organization was formed to head off a second shutdown of the theater. Control is now in the hands of the Apollo Theatre Foundation, headed by powerful Democratic U.S. congressman from Harlem, Charles Rangel.

Leon Denmark, executive director, said that he hopes state and federal grants and corporate sponsorship, like the financing the show gets from Coca-Cola, will supplement box-office receipts. While both he and McDuffie refused to reveal the budget for the amateur nights, he contends that the show basically pays for itself. Tickets are priced from $5 to $25 for the shows.

“We wanted the show to be refocused and streamlined,” said Denmark, who had been the arts manager of Newark’s Symphony Hall.

The board turned to McDuffie whose background includes singing, composing and creative production of advertising jingles. She immediately scaled back the show, which had sometimes been going over four hours, dropping the number of acts from 30 to about a dozen.

“We’re looking to re-establish the Apollo as a venue for exposure for young performers not only for the public but also for the industry,” said McDuffie. “But I want them to see the cream of the crop.”

The Apollo models and their half-time fashion show were dispatched. And while the Wednesday lineup includes rising young recording artists, contestants are the real attraction. There are jugglers, flamethrowers, magicians, comics, singers and dancers--some from as far away as Tokyo and Berlin.

Some competitors are white--the New Kids on the Block were winners early in their career. But most are young African-American vocalists singing R&B; standards, which they hope will give them the best chance at winning the prize money, ranging from $100 for a fourth place finish in the regular amateur night contest to the first- prize purse of $1,250 for the “Super Top Dog” competition--the annual climax to the weekly (“Amateur”), monthly (“Show Off”) and quarterly (“Top Dog”) Wednesday night Apollo rituals.

McDuffie said that she is looking to provide a more “progressive mix”--more on the cutting edge of black culture--in the featured material and noted that she personally reviews hundreds of audio and videotapes to determine who will be invited to compete, while regional contests around the country yield other aspirants. Many applicants are drawn to audition after seeing “Showtime at the Apollo,” the nationally syndicated television series, which features an amateur segment. But McDuffie said that the television presentation, while filmed at the Apollo, is produced independently, does not show the Wednesday night performances and has no connection with her program.

During the January Show Off, 10 contestants patiently waited their turn backstage in the Green Room, two others having bowed out, one because of illness, another because she couldn’t muster the cost of a bus ticket from Chicago. (The competitors are responsible for their own expenses.) Ranging in age from 6-year-old South Carolinian Braxton Brown, an acrobatic break-dancer in epaulets, to mellow-voiced 56-year-old David Williams, they listened nervously as the raucous crowd baited the emcee, Ben Duncan, a local radio disc jockey.

“This is not a nice town,” he taunted them good-naturedly. “Not a nice town at all.”

“Like it or not, this is the place where you’ve got to start,” said Ronnie Smith, the handsome leader of an a capella group called the Brothers in Charge who sang “If I Ever Fall in Love,” a song made popular by Shai. The teens from Queens had met at work, packing crates at UPS, and began singing informally together. “We’re making our dreams come true,” Smith said.

“I’m less nervous, but my heart is beating plenty fast,” said Tia Rivers from Philadelphia, who later, like Butcher, would narrowly escape the hook after singing the Natalie Cole tune, “Inseparable.”

Upstairs, just off stage right, C. P. Lacey, dressed in a clown outfit, limbered up for his thankless role as the “Executioner.” If the boos reach a crescendo during a performer’s number, a siren’s wail is his cue to dance in from the wings and herd the performer off the stage to the Apollo Band’s playing of the “Flintstones” theme. Having competed and won amateur night seven years ago as an impressionist, he was hired to replace Sandman Sims, the Apollo’s veteran Bad News Bear. Since then, he has occasionally been pummeled and attacked by performers.

“It could be that they don’t like the way you’re dressed or the way you walk,” Lacey said, observing that past Apollo crowds booed Luther Vandross off the stage four times before he finally prevailed and that even Ella Fitzgerald has been known to break out into a sweat before going on.

“You have to act humble at the Apollo. They want to feel that they made you.”

The starmakers, on this night at any rate, are mostly young and mostly black. Before the show began, 16-year-old Allyson Martinez from Brooklyn waited on 125th Street with her mother, Hazel, for a group of teens from a national black family organization to join them. “I’ve been hearing about this show all my life,” she said. “We wanted to see it for ourselves. We wanted to come and boo our heads off.”

Or cheer. Indeed, when a young crooner named Von Pariss launched into a Peabo Bryson tune, one white-suited patron, Eva Isaac, stood up in the front row, shouted, cheered, caressed Pariss’ head and waved her arms in ecstasy. McDuffie said that she intended to channel some of that exuberance by introducing a number into the program called “Step Up to the Mike” so the audience members can take a crack. “I can’t wait,” she said. “We’re telling them, ‘OK, here’s your shot. You’ve been booing ‘em. Now you get to see what it feels like.’ ”

There were a few whites in the audience as well at the Show Off; some from downtown Manhattan, like East Village writer Bill Van Parys. But the majority are Japanese and European tourists who have been enticed, according to one middle-aged German, by the “exotic” appeal of Harlem. Denmark maintained that future marketing and promotion would continue to target the Apollo’s basic audience of young African-Americans while reaching out for the “natural crossover” of a white secondary market. “Everybody’s welcome,” he said. “125th Street is safer than most areas in New York City.”

McDuffie said that she may bring in some professional judges whose opinions will be factored into the audience’s applause, which, for now, unscientifically selects the winner. At this Show Off’s finale, Brothers in Charge, the a capella group from Queens, came in fourth; Von Pariss came in third; 6-year-old Braxton Brown came in second and the Bugle Boyz, another a capella group from Sumter, S.C., came in first.

There is some concern that the innovations may well dampen some of the spontaneity and enthusiasm that is a key ingredient to amateur nights. But McDuffie contended that “once we become comfortable with the structure, we’re going to loosen things up again.”

So far, apparently, the changes have met with a guarded but positive response. McDuffie said she was petrified when a performer recently motioned to her to come out from the wings to take a bow during the Show Off. “I thought they were going to boo me,” she said. They politely applauded instead.

As they filed out, audience members offered more opinions: “Hip-hop, gimme hip-hop, rap, reggae, none of this lite stuff,” said one Rasta-hatted brother.

“Where’s Ralph Cooper?” said another.

But New York-born and bred Hazel Martinez, who had never before attended amateur night, is planning to come back.

“I really can’t imagine Harlem without it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.