Kidnapers Use Justices as Messengers : Costa Rica: Supreme Court siege and talks continue, unnerving the nation.

As a siege of the Supreme Court here entered its third day Wednesday, the pace of negotiations quickened abruptly when gunmen released two justices to shuttle proposals between the kidnapers and government representatives.

“We are negotiating,” said Foreign Minister Bernd Niehaus Quesada in his most positive public declarations since four gunmen stormed the Supreme Court on Monday and seized 19 of the nation’s top magistrates and five employees. “I am optimistic . . . this is going to end without bloodshed.”

The attack on the court unnerved this traditionally peaceful country and has sparked a debate on the ability of the government to protect its citizens. Costa Ricans are being forced to face the reality of violence as never before.

“It is a very powerful experience, but it had to happen to us,” said political scientist Constantino Urcuyo. “We were an island with an ocean of violence on all sides, and it was inevitable it would touch us somehow.”

The kidnaping gang, calling itself the “Commando of Death” and headed by a former Justice Department guard and his brother, a former policeman, has demanded an $8-million ransom; they are also seeking safe passage to a South American country.

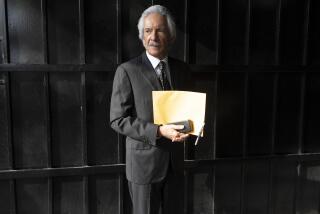

Twice the kidnapers set deadlines for the government, and twice they have allowed them to pass without action. When Wednesday’s 1 p.m. deadline rolled around, two justices, Eduardo Sancho and Alfonso Chavez, were released to deliver a message to authorities.

The missive’s details were kept secret. Three hours after their liberation, the two judges returned to captivity in the court building. About 90 minutes later, they were released again and returned to the Public Security Ministry where government negotiators are holed up.

It was not known if an additional deadline was set. Gilberto Fallas Elizondo, identified by authorities as the ringleader, threatened Tuesday to blow up the court building--and the magistrates inside--if the gang’s demands are not met.

Fallas worked for the court’s Judicial Investigations unit as a guard in charge of handling prisoners. His brother Guillermo until recently was a narcotics agent with the same police unit. Both reportedly received extensive military training; Guillermo Fallas received U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration training.

Authorities said the Fallas brothers borrowed the weapons that they used to storm the court from an unsuspecting rural police officer who was a friend.

Six Colombian army and police experts in kidnap rescue joined the Costa Rican negotiating teams Wednesday after arriving as special envoys from Colombian President Cesar Gaviria. Officials had speculated earlier that the kidnapers were linked to Colombian cocaine cartels, but this theory was later dismissed.

The hostage crisis is taking its toll on the national psyche of a people who have prided themselves on their peaceful culture. While many Costa Ricans breathed a sigh of relief upon learning the kidnapers were Costa Ricans, not ruthless Colombian drug traffickers, that sentiment quickly turned to anger--at fellow citizens who broke the rules.

Costa Ricans have most often been able to blame violence in their country on conflicts that spilled over from the rest of Central America.

That their own people staged a dramatic and potentially tragic act has been a rude awakening. The emotions are being aired on radio call-in shows, in the streets and in the newspapers, where editorial headlines lament: “Requiem for a Democracy.”

Costa Ricans have long cultivated the image of nonviolence, pointing to the abolition of the army in 1948 and the country’s ability to remain on the margin of Central America’s wars through the 1970s and 1980s. The image has helped Costa Rica build a thriving tourism industry and maintain a relatively stable economy attractive to foreign investors.

But the Supreme Court incident has forced Costa Ricans to consider how they can strike a balance between stricter security and the relaxed society they say they enjoy.

“It is partially our fault,” said attorney Alvaro Carballo. “We have resisted professionalizing our police force because of the (tradition) of not having an army. We are a people who have neither had nor desired this feeling of danger always lurking. That’s a difficult thing to change--I don’t know if we want to.”

The government was criticized harshly for its tempered response to two recent hostage incidents, one involving the kidnaping of Public Security Minister Luis Fishman and the other the taking of the Nicaraguan Embassy in San Jose.

In both, Costa Rica chose negotiations over force.

But officials say they will always choose negotiations over bloodshed. Niehaus, the foreign minister, grew angry Wednesday during an impromptu news conference when a Colombian reporter asked him if the government’s soft-handed approach showed weakness. “What do you want us to do? Kill them?” he said, turning sharply to leave. “We do not want violence.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.