‘Jimmy the Weasel’ Fratianno; Mob Figure, Informant

- Share via

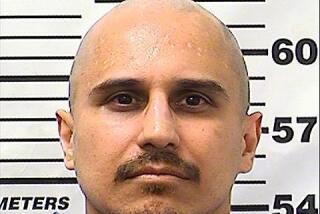

Aladena (Jimmy the Weasel) Fratianno, a longtime Mafia hit man and mob boss before turning FBI informant with a contract on his head, has died. He was 79.

Fratianno, shoot-and-tell author and talk show regular, died in his sleep Tuesday at his home in an undisclosed U.S. city, where he was living under an assumed name, his wife, Jean Fratianno, told The Times.

Phoenix FBI Agent James F. Ahearn, who developed Fratianno as a government informant and witness, Wednesday confirmed that Fratianno had died.

Mrs. Fratianno said her husband had Alzheimer’s disease. Ahearn, who had kept in touch with Fratianno and had seen him a few months ago, said Fratianno had also suffered a series of strokes.

After spending much of his adult life in the mob, Fratianno turned government witness in 1977, traveling the country to testify against fellow mobsters and becoming the highest-paid participant in the history of the federal witness protection program. For the most part, he was able to live quietly with his wife, a San Pedro native whom he married shortly before getting out of the mob.

But his two books, “The Last Mafioso” and “Vengeance Is Mine,” brought him bursts of attention throughout his retirement, as did his occasional appearances on TV talk shows and periodic attempts on his life. Both books were ghostwritten, and Fratianno claimed never to have read either of them.

Indicted in 1977 on charges related to the car-bombing murder of a Cleveland racketeer, Fratianno told a jury that he began considering testifying for the government out of fear for his safety.

In return for his testimony, he pleaded guilty to the charges but served just 21 months of his five-year sentence.

“I thought that if I fight these cases and beat them, I’ll get killed,” said Fratianno, who had claimed that the mob he called La Cosa Nostra had a $100,000 contract out on him.

In a 1980 trial that led to the racketeering convictions of five reputed Mafia figures, Fratianno casually admitted, as part of his graphic description of his 32 years in the mob, that he had committed five murders and participated in six others.

“They tell you when you come in, you come in alive and you go out dead,” Fratianno said of his initiation into the Los Angeles branch of the mob in the late 1940s.

The stylish, 5-foot-9 inch, 180-pound Fratianno, who sported a dyed pompadour, never appeared perturbed by his violent past.

“I don’t let stress bother me,” he said in 1987. “I think that’s very important in a man’s life, in anybody’s life. Stress will age you quicker than anything. And I just try to take it easy.”

Born in Naples, Italy, in 1913, Fratianno came to the United States as a small boy and settled with his family near Cleveland. He first was arrested at 19, on suspicion of rape, but was not charged. Two years later, he was acquitted of robbery charges and, in 1937, he was convicted of robbery and spent more than seven years in an Ohio state prison.

Paroled in 1945, he moved to Los Angeles and fell in with underworld figure Mickey Cohen. In 1951, he was arrested but later released in connection with the gangland-style slaying of two mobsters believed to have plotted to kill Cohen.

Fratianno’s next prison term came with his 1954 conviction for attempted extortion; he served 6 years and 3 months, mostly at San Quentin. In 1968, he pleaded guilty to charges stemming from phony pay agreements with drivers at a trucking company he owned, and in 1971 he entered another guilty plea, this time for extortion.

In the late 1970s, Fratianno became acting boss for the Los Angeles mob. It was then, he said, that he became the target of a murder contract--and the hit man became the songbird.

Life in retirement did not always go smoothly for the man who had once gambled in Las Vegas with Bugsy Siegel, lunched in Los Angeles with civic leaders and cavorted with fellow mobsters on the Sunset Strip.

He sued his handpicked biographer for his first book, “The Last Mafioso,” saying it contained false quotes. He blamed the second book, “Vengeance Is Mine,” for his being dropped from the witness program’s payroll in 1987.

The Justice Department, noting that it had spent nearly $1 million on the Fratiannos in 10 years, said any further payments might make the witness protection program appear to be a “pension fund for aging mobsters.” A spokesman assured The Times at that time, however, that Fratianno would have continued access to aspects of the program, including a false identity and U.S. Marshals Service protection in “danger areas.”

Fratianno, however, claimed that the cutoff was a complete ouster from the program and that it left him “a dead man.”

“They just threw me out on the street,” he said at the time. “I put 30 guys away, six of them bosses, and now the whole world’s looking for me.”

With his scrambled syntax and matter-of-fact accounts of Mafia hits, Fratianno horrified and intrigued the public during his court testimony and talk show appearances.

“When the boss tells you to do something, you do it. You don’t do it, they kill you,” he told an interviewer in 1987. “I wouldn’t kill an innocent person, no way. They tell me to kill an innocent--I tell them to go to hell.”

He typically would talk of his shooting of Anthony Trombino and Anthony Brancato, two accused murderers who were harassing the owner of Las Vegas’ Flamingo Hotel to the distress of the Los Angeles crime family.

“They robbed the Flamingo, and they were bothering some guys that we were, you know, in partners with,” Fratianno said. “And I told them to lay off, and they didn’t do it. And we just had to kill ‘em.”

In a telephone interview Tuesday night, Mrs. Fratianno recalled her life with the former Mafia hit man.

“I loved my husband very much; he was sweet,” she said. “He was a success because he went into the (witness protection) program and he survived. . . . It is a better program now because of him.”

She met her future husband in an airport 1966 and married him in 1975, when she was 32 and he was 59. She said she had no idea he was involved in organized crime until after their wedding.

“I just thought he was in the trucking business,” she said.

Times staff writers Ronald J. Ostrow in Washington and Myrna Oliver in Los Angeles contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.