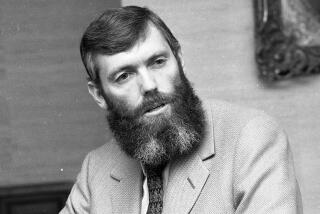

2 Monastery Founders Pray for More Members : Worship: Brothers Steven and Peter gave up their worldly goods to establish the Society of St. John. Their goal is to serve humanity through the fine arts.

EAGLE HARBOR, Mich. — Ten years ago, Brother Peter and Brother Steven abandoned big-city careers, worldly possessions, even surnames: They would establish a monastery to serve God and humanity through the arts.

They settled on the beautiful but remote Keweenaw Peninsula in the northernmost corner of Michigan. Their century-old frame house was uninsulated, and their firewood ran out the first winter. There was no running water. They credit neighbors’ generosity and divine mercy with keeping them alive.

The Society of St. John, as their community is named, has come a long way since that desperate winter of 1983. But it has a long way to go--largely because the two founding monks remain its only members.

At least five monks are required for a monastery to receive Catholic Church recognition. A number of candidates have shown interest, but none has stayed longer than a couple of months.

Each day they pray for “men of like mind and heart to share in the life, work and love of this community.” They patiently wait, running a small bakery to support themselves and planning for the growth they are sure will come.

They say they have never regretted the path they chose.

“All the trials resulted in spiritual growth,” said Steven, 47. “That’s what sustains the monk. . . . You struggle, you worry, you grow, you become closer to God.”

They met in the early 1970s while students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Peter went on to manage restaurants while Steven directed an art center and conducted a choir and orchestra.

Arts projects in the Detroit area brought them together again. They discovered that they shared deep religious faith and frustration with secular life.

The arts, they agreed, should be a path to godliness--a form of worship inspiring piety and faith. That didn’t seem to be happening for the troubled urban youths with whom they worked.

Even church was dissatisfying. Peter and Steven saw traditional messages of discipline, clean living and repentance of sin giving way to feel-good music and emphasis on boosting self-esteem.

“It’s campfire music . . . composed for pop musicians. You might hear it in church, but also at the bar down the street,” Steven said.

They finally decided to set the example--to renounce worldly pursuits for a monastic life of prayer, poverty, chastity and obedience.

But they also wanted to minister through the arts, a twist that other monasteries didn’t offer. That meant starting their own.

They came to this spot because it offers isolation and affordability--as well as breathtaking views of Lake Superior, a beach strewn with colorful pebbles, thick woods and the nearby Jacob’s Creek waterfall.

As Benedictine monks, they follow the rule for daily living written by St. Benedict in the 6th Century. They rise hours before dawn for vigils--Scripture readings and recitation of Psalms and prayers.

The rest of the day consists of meals, manual labor, joint prayer sessions and private prayer and meditation. The monks usually retire shortly after sundown, following the evening prayer.

The men arrived in the Keweenaw with no plan for earning a living, trusting God to show the way. They relied on family and friends the first winter, then spent the summer picking berries and making jam to cover expenses.

A couple of years later, they opened a shop, called the Jampot, in an abandoned roadside burger stand near their house. They have since expanded the kitchen with the help of equipment donations from churches and businesses. The 7,000 customers who visit each year find the counter packed with jellies--every flavor from wild thimbleberry to spiced apple--plus breads and fruitcakes.

Summer tourists keep Peter and Steven laboring day and night making baked goods, jams and jellies for the shop. But only a few locals stick around for the long winters, when the monks close the Jampot and spend more time in prayer and contemplation.

They wear jeans and gym shoes underneath hooded, gray tunics. They have a truck and telephone. Their community house is heated with firewood, but they use a computer to compose a quarterly newsletter, “Magnificat.” It keeps about 1,200 supporters familiar with the monastery’s progress and offers mail-order goodies from the Jampot.

Mingling with so many people through the store might seem at odds with the tenet of separation from the outside world. Some monks are nearly always silent. But for Peter and Steven, social interaction is virtue borne of necessity. The Jampot pays the bills and enables them to witness and minister.

They want their monastery to become a hub of religiously oriented arts, with concerts, seminars and perhaps a summer art center. They open guest houses on their property for religious retreats, and even offer a “junior monk” program for interested teens.

“We’re not here to escape the world,” Steven said. “We have a call to deal with the world.”

They have bought 67 acres of land and hope to break ground next year on a chapel and “community house” with living, study and worship space for up to 24 residents. Long-range plans include construction of an abbey and an orphanage.

“We’re happy, and we believe other men will see that and want to take part,” Steven said. “When it’s time, they will come. Until then, we are here and will live the life until we die.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.