Fieldworkers Labor Alongside the Jet Age : Agriculture: Each year, hundreds of Latino men and women pick onions in Palmdale under the flight path of an Air Force plant. The harvest is part of L.A. County’s third-largest crop.

Under the flight path to U.S. Air Force Plant 42, where sleek jets and lumbering cargo planes soar overhead, Salvador Beleche and Luis Mendoza have been living in hovels made of burlap bags and plastic sheeting draped over Joshua trees.

In an annual rite joined by hundreds of other Latino men and women, Beleche and Mendoza have come to the Antelope Valley to work the region’s onion harvest. And their presence is proof that although Los Angeles County’s agriculture industry may be down, it is not yet out.

Antelope Valley onions have become the most highly valued vegetable crop grown in Los Angeles County, although producers say the region’s harvest is little known to most people. This year’s yield is expected to approach 50,000 tons and will be shipped around the world.

Los Angeles was the nation’s most productive agricultural county during the 1940s. But its farmland has been steadily consumed by urbanization. The still-open spaces of the Antelope Valley remain as sort of a last outpost of major farming in the county.

From 1989 to last year, the county’s annual agricultural output--including nursery items, fruits and nuts, crops, vegetables and animal products--fell from nearly $316 million to just $201 million. And $149 million of that was related to nursery products, county agriculture officials say.

Onions from the Antelope Valley, the only place in the county they are grown in quantity, were the county’s third most valuable agricultural product, worth $13.3 million last year, behind only trees and shrubs ($105 million) and bedding plants ($23.6 million), officials say.

Yet the harvest carries a human price. To farm workers, onion economics are measured in 94-cent increments. That’s the typical pay for each 80- to 100-pound burlap sack of onions they pick. And for 60 to 100 sacks a day from dawn to sundown, a worker may take home $50 to $80.

It was an eerie scene recently in Palmdale. As C-130 and C-141 military transport planes, each worth tens of millions of dollars, circle above to practice takeoffs and landings at nearby Plant 42, some 400 laborers are toiling below in a sandy 80-acre field picking brown onions.

The land is owned by the Los Angeles Department of Airports, which someday hopes to build a major airport there. But in the meantime, because the property must remain undeveloped, airport officials lease it out to the valley’s onion growers to gain a small source of revenue.

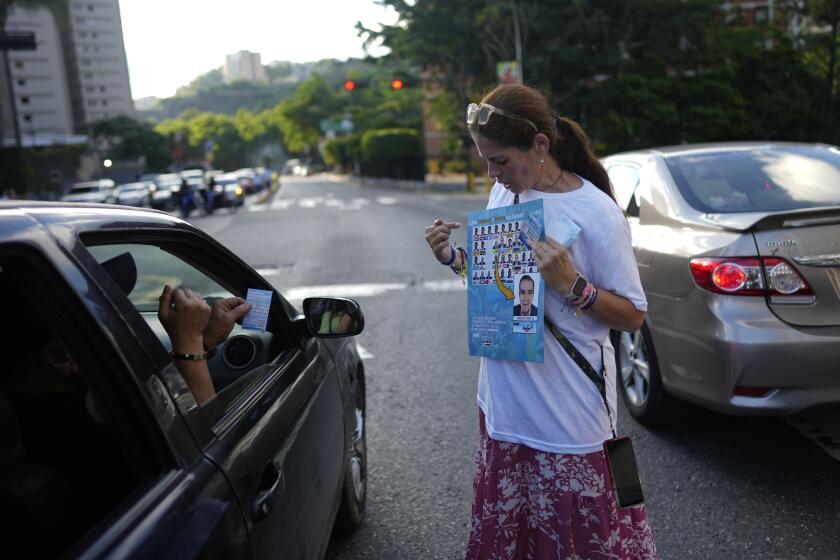

Just off a usually deserted stretch of 50th Street East near Avenue M, scores of cars, pickup trucks and campers have gathered at the edge of the onion field in the early morning. Some men and women are picking while others are sharpening their tijeras, or scissors, as they wait to start.

Arnulfo Camarillo, 36, wearing a straw hat to provide some shade, says he has been in the area several weeks for the harvest. Camarillo, like many of the workers, says he follows the various crop harvests around Central and Southern California through the year.

Camarillo lives to the north in the Kern County town of Lamont, but many of the workers are from Texas and Mexico, as well as Guatemala and other Central American countries. Field supervisor John Paredez said many return home annually for a winter break.

These days, said Paredez, a Bakersfield resident, there are more laborers than work, especially since the recession has pummeled Southern California’s construction industry, erasing its more attractive jobs. Still, he says of his field crews, “they make way better than minimum wage.”

Camarillo says he is slow; he figures he fills 50 sacks of onions in a day, netting about $40. Standing, he bends over, pulls several from the ground and then clips their stalks and roots. Asked if the workers consider any one crop the best to work, he replies: “They’re all heavy. It’s tough.”

After working in the fields for three years, Camarillo says he wants to find a job in Las Vegas, perhaps as a janitor, where “it’s nice and clean” and where people “are eating all the time.” In the meantime, he eats Mexican food from a vendor in a truck and sleeps down the road at a camp.

About a mile from the field, set back off the road near a cluster of trees, is the camp where many of the workers return at night to sleep for free. But when people talk about the Antelope Valley having among the county’s most affordable housing, this is not what they have in mind.

The location is miles from much of anything, either Lancaster to the north or Palmdale to the south. It is part of the no man’s land created around Plant 42 because of the jet traffic and the vacant land for a future airport. But at least for this year’s onion harvest, it is a place many call home.

Home for Beleche and Mendoza is a collection of makeshift shelters, some as simple as an uprooted toppled tree covered with burlap bags. Others are as complex as Beleche’s family-sized hovel built around a standing Joshua tree.

Burlap bags, sheets of plastic and cardboard panels are the building materials. Sometimes the floor is just dirt, and sometimes it is more bags, blankets or cardboard. Strewn about are empty beer cans, litter and other debris.

Although there are portable toilets in the onion fields, none are visible at the camp. Residents get their water from a metal tank. Some vans and cars sit parked nearby, with people resting in the shade from the midday sun. Nearby, one group of men has a portable stove set up for eggs and oatmeal.

Beleche, a short, wiry man, insists that his living conditions are tolerable. With Mendoza interpreting, Beleche notes that one can see many similar shelters--absent the Joshua tree--on the streets of Downtown Los Angeles.

Back at the onion field, Paredez acknowledges that similar camps have sprung up in the area. He says he and his employer have nothing to do with the camps, that the workers are paid but where and how they sleep at night is their own doing.

Miles to the north in an industrial area of Lancaster, it looks as though a snowstorm has struck the Giba-Wheeler Farms complex as the desert winds blow flurries of white onionskins across the parking lot of one of the Antelope Valley’s big three onion growers.

The onions along 50th Street East belong to Giba-Wheeler, part of about 700 acres of onions in the Antelope Valley that partners Phil Giba and Gene Wheeler are growing this year. Inside, Giba stresses that farming today is all about big business.

In the two weeks since the harvest began, Giba--an inveterate Lakers fan who delivers fruit each week to Earvin (Magic) Johnson--figures that Giba-Wheeler has shipped about 110 truck containers, nearly 2,500 tons, of Antelope Valley onions to Japan.

Normally, the Japanese grow a lot of their own onions, but monsoons in recent weeks ruined much of that crop, Giba said. The demand has turned what had been lackluster market prices into healthy profits, at least for now.

From August through October, Giba-Wheeler, a partnership formed in 1984, expects to harvest about 21,250 tons of the 40,000 to 50,000 tons expected from the valley. The majority will supply Southern California-area supermarkets between now and February, Giba said.

Around the world, from Taiwan to Dubai to Australia, where some of the company’s onions go, Giba says Antelope Valley onions are recognized as being the best of the winter crop, the spicy variety grown at this time of year. Yet many Antelope Valley residents do not know his company, Giba says.

About 100 people are working 10 hours a day, six days a week inside the company’s plant, an old turkey slaughterhouse, sorting, bagging and shipping. Onions like his, Giba says, are better if picked by hand .

To Southern California consumers, the Antelope Valley onion harvest is a slice of spice for a summer barbecue. To Giba, it is his business and an industry to tend. To Camarillo and the other farm workers, it is a way to eke out a living on dusty back roads that most people never see.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.