National Agenda : Anatomy of Germany’s Nationwide Health Care System : The much-admired program is beset by problems, including a bureaucratic logjam.

BERLIN — Her waiting room empty, her last patient out the door, Dr. Sieglinde Brandstaeter stared at the four-inch-high stack of cards in front of her.

The cards constitute the other part of her work--the part that usually begins after 10 to 12 hours of dispensing medical treatment and advice, when the overworked pediatrician dutifully sits down to face her paperwork.

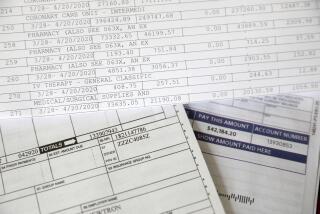

Like almost all of Germany’s 98,000 private physicians, she must categorize and submit detailed accounts of her treatments to an administrative clearinghouse for payment, in what has gradually become a bureaucratic nightmare.

“When I sit here late at night, I’m so exhausted I can hardly see,” she said. “Somehow, it’s all gotten steadily worse.”

Growing bureaucratic demands are only one problem that plagues Germany’s much-admired national health care system--a system that historically has enjoyed such success that it has been oft-mentioned as a potential model for Clinton Administration reformers.

As President Clinton searches for ways to extend America’s medical care system to all, and at the same time to contain its exploding costs, the struggle to sustain Germany’s successful program is a reminder that even the industrialized world’s best health care systems find themselves confronting enormous problems.

“This is a system that can’t be sustained in its present form,” claimed Hans-Juergen Thomas, chairman of the Hartmann League, Germany’s most powerful association of medical professionals. “The doctor is under growing financial and professional pressure, and sooner or later this is going to take its toll on patient care.”

Despite its problems, it’s not hard to understand why Germany’s 110-year-old system caught Clinton’s interest. After all, it already has achieved much of what reformers in the United States can merely dream of: universal, unlimited medical coverage that provides access to uniformly high-quality services for everyone, all with disciplined cost controls.

Germany’s health care costs annually run about 8% of gross national product, compared to the 12% of GNP shouldered by Americans. Further, the German costs have risen far more slowly than in America--about 20% in the 1980s, compared to 50% in the United States. Mainly because of recent reforms, Germans’ costs actually declined by 1.5% in the first quarter of this year.

That this system also offers patients the freedom to choose their own doctors, and doctors the freedom to work privately, free of any large, centralized control, merely adds to the attraction for Americans.

The German system, in brief, works this way: Germans pay into one of more than 1,200 government-supervised health insurance funds, their fees being split 50-50 with employers. (The government covers half the cost for pensioners and the jobless.)

The insurance funds then pay the doctors. Hospitals are on a separate budget, with a separate staff of salaried doctors.

For the patients, this system offers quality care with hardly any paperwork and no financial worries. To be sure, their monthly contributions to the health insurance funds can run as high as $400. But they buy both total health care security and entry into a giant medical “playground.”

For example, a new mother who underwent an unexpectedly complicated birth that included a Cesarean followed by a 16-day stay at a large Berlin hospital was presented the bill for her and her new baby’s care: $20. There was a fee of $4 for each day’s stay exceeding 11 days, a hospital staffer explained. No other money changed hands; no claim forms were required from the patient. Whether for a routine visit to the doctor’s office or major surgery, the same rules apply.

Adequate funding means the German system works without the horror stories of gradually collapsing services and yearlong waits for routine surgery associated with some other state-run programs, such as the British national health system.

Consider the health care perks to which Germans are entitled:

* Payment of all costs exceeding $16 incurred in traveling to and from the place of medical treatment.

* Access at nominal cost to the uniquely German “cure”--a four-week holiday at a health care retreat where, for example, overworked managers can decompress and get a crash course on how not to abuse their bodies, or where a mother can escape family stress, discuss problems with other mothers and be reassured that the health care system will deliver hot meals to her family’s door each day while she’s away.

* A death payment of $1,250 issued to the next of kin.

Health care administrators here say the key to controlling costs has been the steady refinement of a system first implemented by Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s as part of a fledgling welfare state to quell worker unrest and undercut trade union influence.

They note that membership in nonprofit health insurance funds has steadily grown from 10% to about 90% of the population; the collective monopoly of these funds, coupled with legal restrictions on their expenditures, provides enough clout to keep the lid on costs.

“The United States has shown the world that health care is one area where competition has little to do with containing costs,” said Gunnar Griesewell, a senior official in the German Health Ministry.

As part of a far-reaching reform implemented late last year against vehement protests by the medical profession, the government imposed savings of $6.5 billion on the system, including limits on the number of private physicians and reduction of dental coverage.

The centerpiece of this plan was an arbitrary cap of $15 billion placed on the allowable cost of prescription drugs, with doctors made collectively liable for up to $165 million for any overruns.

That move followed a 3-year-old Health Ministry order that created a “negative list” of drugs--pharmaceuticals considered overpriced and for which patients must pay.

Under last year’s reform, patients were also forced to ante up token contributions ranging from $1.75 to $4 per prescription to help finance all drug costs.

While the measures, shaped by Health Minister Horst Seehofer, were voted through the federal Parliament last December with the backing of all four major parties, physicians denounced the package.

Still, a drop of between 20% and 30% in last January’s prescription volume over the same month of the previous year has left only smiles at the Health Ministry. “Everyone knew there was a terrible oversupply, but we had no idea we’d achieve this kind of success,” Griesewell said.

Physicians, however, argue that any official satisfaction is premature.

They believe that these and other cost controls endanger the very system in which they work. Physicians association chief Thomas claims, for example, that in real terms, the income of private doctors has dropped by 20% over the last decade and that last year’s reform will mean another 20% drop this year alone.

“The system sets doctor against doctor and is going to come to no good,” he said.

After tax and professional costs, a general practitioner in Germany averages about $45,000 in annual income; a specialist averages about $60,000, heath care industry figures show.

At the heart of the physicians’ complaint is the “point system,” under which doctors are awarded points rather than money for services rendered. For example, treating a small wound gets a doctor 100 points; if stitches are involved, the value rises to 160 points; a routine physical examination generates 320 points, and removal of a brain tumor, 7,500.

“Every move I make, every word I exchange, gets pressed into a number,” Brandstaeter said, nodding toward the desk where more stacks of cards waited.

With the insurance funds in each of Germany’s 16 states limited by law to paying no more in claims that they take in in contributions, the value of a point is determined quarterly by a simple calculation: the available funds divided by the number of points racked up by doctors during the quarter. “We have basically put a cap on doctors as a group, not as individuals,” Griesewell said.

The point value invariably falls in the winter, when many are sick, and rises in the summer when treatment volume eases.

While such a system leaves the patient worry-free, it saddles doctors with major burdens:

* Because the point volume must first be calculated and checked, physicians wait months to learn what they have actually earned.

* To get paid at all, doctors must submit precise written descriptions of exactly what procedures were performed with their corresponding point value. That bureaucratic exercise, physicians estimate, adds 20% more time to a workweek that already averages about 55 hours.

* To earn more, physicians not only must work harder, but they also must outperform their colleagues to get a bigger slice of a financial pie that remains constant. “That a doctor’s income can fall, even if he works harder, is untenable,” Thomas said. “It can’t go on like this.”

* The German system separates doctors into two classes: salaried, generally lower-paid hospital physicians and private practitioners.

Despite these strains, most doctors agree that more drastic savings must be made if the financing of the system is to be assured. Germany’s aging population, for example, presents a serious challenge to both containing costs and sustaining income.

But as talk of reform intensifies, hard-pressed physicians believe that the system’s long-term survival can be achieved only by cutting back on luxuries such as the “cures” and passing at least some of the bureaucratic costs on to patients.

Indeed, some doctors argue that, besides providing more funds, such a move would generate patient awareness of the cost of treatment. “Patients have to take on more responsibility, they need to know what things cost,” Thomas said.

Christoph Hilsberg, a Berlin specialist in youth medicine, recalled seeing one patient virtually every week until the patient opted out of the state-controlled system and became one of the small minority of Germans to insure themselves privately under a plan that grants a hefty rebate on premiums for staying healthy. “Suddenly, his visits dropped to about one or two a year,” Hilsberg said.

Long hospital stays are also legend in Germany and occasionally suspect. Hilsberg recalled how, as a Hamburg official in the 1960s, former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt once evicted 15,000 hospital patients overnight to make room for thousands of homeless in the wake of a major flood. “Not a single patient died,” Hilsberg noted.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.