COLUMN ONE : Teaching Patriarchs to Lead : Inspired by a football coach, Promise Keepers tells Christian men to take charge of their families. Critics fear politics may overshadow.

Suppose 50,000 cheering, foot-stomping men show up at Anaheim Stadium not to watch the California Angels, but to confide in one another about sexual indiscretions, anger at their fathers, or being insensitive to their wives and children.

Suppose they laugh at their male habits--such as channel surfing with the remote control or refusing to ask for directions.

Then suppose they admit that they are self-absorbed, followed by penitential tears and promises to be better husbands, fathers and grandfathers.

This is Promise Keepers, a burgeoning men’s movement rooted deeply in evangelical Christianity that is sweeping the nation.

In the three years since its founding by controversial University of Colorado football coach Bill McCartney, about 20,000 men have signed pledges committing themselves to improve as husbands and fathers. By the end of July, an estimated 225,000 men will have packed stadiums and sports arenas from the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis to Folsom Stadium in Boulder, Colo. The conference last month in Anaheim was the first of six to be held this year.

The agenda? To strengthen the family and restore the nation by exhorting men to become “promise keepers instead of promise breakers.”

Promise Keepers asserts that men, by walking away from their family duties, are responsible for much of America’s societal dysfunction, which the group’s leaders say includes high school dropouts, a soaring crime rate, racism, divorce, homosexuality and abortion. The women’s movement, Promise Keepers says, is at least in part a reaction to the pain and abuse women suffer at the hands of men. This analysis worries critics, who say that such talk could move the group beyond the family to political activism.

Some observers see Promise Keepers as the latest turn in the search for male identity in a fast-changing and conflicted society. In American history through the 1950s, the family structure was unabashedly patriarchal. The 1960s and 1970s ushered in the Sensitive Man who acknowledged a feminine side and sought to nurture. The 1990s brought the Wild Man, hairy-chested and testosterone-driven, extolled in author Robert Bly’s bestseller, “Iron John.”

Now, Promise Keepers’ slogan is: “A man’s man is a godly man.” In some ways, it is a throwback to the days of “Father Knows Best.” Dad is still in charge, but he’s kinder, gentler and a lot more spiritual.

McCartney said the inspiration for Promise Keepers came in 1990 during a drive from Denver to Pueblo. He and a friend were talking about the need for a men’s ministry. Later, at a luncheon, he noticed that some fathers in the audience had invited their sons along. The scene brought to mind a verse (Proverbs 27:17): “Iron sharpens iron, and one man sharpens another.”

Within weeks, others joined McCartney in brainstorming and prayer. The next year Promise Keepers drew 4,200 men to its first conference at the Coors’ Event Center in Boulder. Now the group has a $3.8-million annual budget and a staff of 70 in Boulder.

In 1996, Promise Keepers hopes that 1 million men will descend on Washington--four times the size of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 civil rights rally there. They will kneel in prayer between the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument to seek forgiveness as men and ask God to restore America.

“This out here is just the beginning,” McCartney said in an interview during the Anaheim Stadium conference. “There is an explosion going on in men’s hearts.”

Some observers, mindful of attempts by the religious right to politicize the Gos pel, wonder where it all will lead. Promise Keepers’ religious tenets could put it on a collision course with the women’s movement, gay rights advocates and those who are suspicious of hidden political agendas.

For example, Promise Keepers is unapologetic in asserting man’s role as head of the family. It denies that it has a political agenda.

But at the Anaheim conference, one preacher’s remarks were tinged with political rhetoric. The Rev. E. V. Hill of Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles spoke darkly about the teaching of evolution, the abortion “epidemic,” and the “satanic” American Civil Liberties Union.

At one point, the ACLU threatened to sue the University of Colorado, charging that McCartney was injecting his religious beliefs into coaching. The group noted that he had assailed homosexuality as ungodly while speaking from a university podium.

The ACLU decided not to sue after university officials made it clear that they expected McCartney to keep his religious beliefs out of the locker room.

“They deny being political and focus, at least in public, on the spiritual,” said Arthur Kropp, president of People for the American Way, a liberal watchdog group in Washington. “But (McCartney) talks about America being in a moral decline, that they’re engaged in spiritual war, which I suppose is equal to the cultural war that Pat Buchanan talks about. . . . I think there is a political agenda there.”

Randy Philips, Promise Keepers’ president, acknowledges that political involvement is possible. But so is serving the poor or working for racial reconciliation.

“Our focus is changing men’s hearts. When they’re changed, they change a family, and a family can change a community,” said Philips, 41, an ordained minister who belongs to an evangelical church in Boulder. “A community can change a nation.”

*

Lights flood the infield at Anaheim Stadium. It is opening night.

From the left-field bleachers a shout, reminiscent of a high school cheer, goes out: “I love Jesus, yes I do! I love Jesus, how ‘bout you?” The mood is celebratory and, in the spirit of men, vaguely competitive. From across the stadium comes the right field’s still louder rejoinder: “We love Jesus, yes we do! We love Jesus, how ‘bout you?”

Soon, the 50,000 men rise to their feet as the band strikes up a rousing, rocking rhythm, “Let the Walls Fall Down!”

One hundred thousand uplifted hands in perfect synchronization sway like palm fronds in the wind. Like a well-tuned engine, they compress the air, exploding in rhythmic concussions of clapping that sound like a locomotive barreling down the tracks.

These older men with paunches, middle-aged men with graying temples, young men with complexions as fair as the dawn are entering Robert Bly’s woods. They are singing songs around the campfire. They are beating drums, summoning the wild man from within. But this time, Jesus is their guide.

“Back to back, warrior to warrior; back to back, defending each other, standing together, we’re building the Kingdom of God,” they sing.

The citadels of male stoicism and self-reliance begin to crack. Men put their arms around each other like boyhood pals. Brotherhood is replacing competition.

Sociologists call it collective effervescence, the point at which one’s individuality is subsumed into something bigger than oneself. Promise Keepers calls it the spirit of Almighty God.

Loud whoops, applause and whistles end the singing.

Soon the men will confront their wounds.

The Rev. Daniel DeLeon of the 4,000-member Templo Calvario in Santa Ana is at the podium, sharing a joke about who wears the pants in the family. But the underlying issue could not be more serious to those present: the male role.

Too many men, DeLeon and other preachers declare, have defaulted on their responsibilities.

The statistics he cites are condemning. Every day, DeLeon says, 2,500 American couples file for divorce, and 90 children go to foster homes. Among teen-agers, 500 turn to drugs, 1,000 turn to alcohol, 1,200 commit suicide and 2,200 drop out of school.

It is time, the men are told, to be fathers and husbands who set the tone for their households.

Promise Keepers insists that gender roles are given by God. One of its books, “Seven Promises of a Promise Keeper,” enjoins men under the subheading, “Reclaiming Your Manhood,” to tell their wives: “Honey, I’ve made a terrible mistake. I’ve given you my role. I gave up leading this family, and I forced you to take my place. Now I must reclaim that role.

“Don’t misunderstand what I’m saying here,” the author cautions. “I’m not suggesting that you ask for your role back. I’m urging you to take it back. “

That kind of emphasis worries the Rev. Ron Benefiel, pastor of the First Church of the Nazarene in Los Angeles and a leader in evangelical Christianity.

“I think we hear the world is a mess because men have given up leadership,” said Benefiel, who was an observer in Anaheim. “That has the seeds of discrimination. Instead of race, it’s gender.”

He cautioned that Promise Keepers could easily cross the line from encouraging male leadership to reinforcing male superiority.

Judy Balswick, director of clinical training in the department of marriage and family therapy at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, shares Benefiel’s concerns. She would prefer to see men and women work together as “co-parents” and share leadership in the home. “We don’t want two separate movements again,” she said.

Still, she said that for those who believe in a strict male “headship” model, Promise Keepers can help by urging men to temper their authority with intimacy, tenderness and nurturing.

McCartney, 52, a former Roman Catholic who now belongs to an evangelical church, believes that it has always been in God’s plan that the man should be the family’s spiritual leader.

He tells the Anaheim conference that between 1950 and 1990, polls showed that the home slipped from first to fourth place as the most influential factor in the lives of children, behind peer groups, television and schools.

“My question to you is, why is the home fourth?” McCartney asks. “Could it be that there’s no one home? Could it be that there’s no one home that has lived up to their promises?”

Why men ignore their responsibilities or are emotionally absent from their wives and children has been the subject of countless studies. Some argue that stoicism, self-absorption and the search for identity are rooted in the failings of men’s fathers to nurture them. Others say careers take precedence over family.

Talking about fathers is gut-wrenching stuff for many of the men at Anaheim Stadium. “What we sense here now is sons who did not have a father, or (a father who) was not one to speak and to show us his love,” Promise Keepers President Philips declares. A hush falls over the stadium.

Brian Taylor later said he could feel the tension around him. “They were crying. There was a loss of words. They didn’t know what to say,” said Taylor, 25, an elementary school teacher from Oceanside.

All forms of the men’s movement, whether secular or Christian, point to the same thing, said Robert Hicks, a professor of pastoral theology at the Seminary of the East in Dresher, Pa. “For the last couple of decades, all has not been well with men. There is a deep-seated, almost desperation going on, a male hunger, a problem that reflects the father affections and affirmations we didn’t have as sons being raised,” said Hicks, author of “The Masculine Journey.”

Promise Keepers doesn’t dwell on past grievances or sins, however. It does not want men to wallow in self-pity.

It urges men to acknowledge their wounds--and broken promises--repent and, with the help of other men, do better by their own sons, daughters and wives.

This can be a tall order, particularly for men with unresolved life issues. McCartney says that men cannot do it by themselves. They need help.

Promise Keepers asks men to form small groups of confidants who will not only regularly listen and offer support and prayer, but hold those in the group accountable for their actions.

*

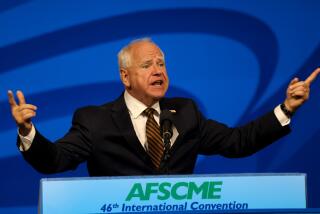

The coach is onstage. It’s halftime in the lives of thousands of men all around him. This is the pep talk that, with God’s help, McCartney hopes will lead them to a spiritual victory.

By his own account, he’s “a mess.” He has had his share of guilt and pain, when he put football ahead of everything else, including his wife and children.

In 1988, he was devastated by his 19-year-old daughter’s announcement that she was carrying the baby of the coach’s star quarterback, Sal Aunese. He stood by his daughter. Later, Aunese was found to have inoperable stomach cancer, and McCartney spent hours at his bedside, leading him to accept Christ just days before he died.

“I hope it doesn’t take other guys as long as it took me to realize how important a father is to his children,” the coach told Promise Keepers’ magazine, New Man, a few years later.

But McCartney is on home turf now. He is in a stadium, and nearly everyone in it is a fan. His voice is thick with emotion. His words are edged with a wisp of the penitential.

“It isn’t like we stopped loving our wives,” he said. “But they said, ‘What happened to that guy that had all of his focus on me?’ And we went after the career. . . . We took our eyes off our loved ones and we took on the challenge of the American dream. But guess what? That’s not Almighty God’s design for us at all.”

McCartney has a plan.

“We say: ‘Lord, it’s not about me. It’s about you. Lord, when I walk through that door . . . it’s not going to be about my appetite. It’s not going to be about my fatigue. . . . I’m not going to walk in the door and say, ‘What’s for dinner?’

“I’m going to walk in the door and I’m gonna say, ‘Honey, how are you? ‘ And I’m going to come alongside her and I’m going to see her needs and respond to (them).”

Women such as Connie Schaedel of LaMirada say they notice a difference in their mates. Her husband, Granville (Bud) Schaedel, was active in Promise Keepers before his death at age 60 in April.

“Our relationship, our marriage, became even more complete, even more whole, as a result of the way he felt he could express himself . . . after the Boulder conference,” she told reporters. “It was an incredible blessing.”

But what if the women do not respond in kind? McCartney tells the men to be patient. Never give up. God will provide.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.