Uneasy Street : Some New Threats in Old Places Create ‘Anxiety’ for the ‘90s

A child at play is slain by random gunfire. A carjacker shoots a motorist in broad daylight at a busy intersection.

Foods we once enjoyed with impunity are labeled hazardous to your health.

In the ‘90s, “much of what we are surrounded by is a threat,” says Bonnie Earls-Solari, curator of “Anxiety: View of Contemporary Life,” a group exhibition at the BankAmerica Gallery in Costa Mesa that attempts to shine light on these dark times.

“So much of what we read in the news has to do with people who are no longer secure doing things that were once thought to be” perfectly safe, Earls-Solari says. “Sitting and watching TV in our own homes, driving in our cars, breathing the air, eating the things we eat. . . . People sometimes begin to feel that every aspect of their life is under attack.”

Representational and expressionistic paintings, prints, photographs and drawings by 20 artists make up “Anxiety.” Images of society’s hapless victims abound and a sense of insidious malevolence lurks like a cat burglar.

Most of the works date from the 1980s, during which time BankAmerica Corp. and Security Pacific Corp. independently acquired the bulk of their respective art collections. Those collections were combined when the banks merged two years ago.

Modern-day Angst “has not just happened,” Earls-Solari said in recent phone interview from her San Francisco office. “It developed over a period of time and references to it can be found in a number of earlier works.”

Richard Bosman’s prints best represent the show’s main theme of new threats in old places, the curator said. In “Drowning Man I” (1981), for instance, an innocent ocean dip has turned topsy-turvy for a frantic figure seen upside down, underwater, his panicked eyes open wide, his mouth agape in a silent scream.

*

Evil literally hits closer to home in a satiric comic-strip-like lithograph by Glen Baxter that depicts father and daughter at the dinner table. His face is splattered with debris from a mangled “exploding fork” he holds over a plate of meat, peas and potatoes in “It Was the Fourth Time that Daddy Had Fallen for the Exploding Fork Routine” (1984).

Urban alienation is personified by Leo Rubinfein’s haunting photograph, “Hong Kong” (1980), Earls-Solari said. A man and his dog stand on a wharf watching whitecaps and boats pitch about on a windy day.

“We have become cut off from lots of things that provide a sense of community and family support and confidence in our society that things would be OK,” she said. “In some of the works, there are no people, which almost magnifies that isolation, that emptiness.”

One such unpopulated piece also bespeaks the “ambiguity” and “uncertainty,” Earls-Solari said, of modern life, which can be shaken one day by earthquakes, the next by a scientific discovery that shatters previous theories (such as one recently refuting evolution’s uninterrupted, steady pace) or condemns decaf.

In Hollis Sigler’s “No Longer Dreaming” (1983), everything’s akimbo in a couple’s unoccupied bedroom--inexplicably under siege--where the bed’s a-rockin’ and a-rollin’ and tea is tossed like a sideways waterfall from a cup thrown from a toppling bedside table.

“You don’t really know what caused it, what happened to turn that bedroom upside down,” she said.

Similar unseen malevolent forces are the trademark of one of the show’s best-known artists: New Yorker Robert Longo, once dubbed by L.A. Times art critic William Wilson as the master of Apocalyptic Pop, whose art “decries a culture that maneuvers its citizens like so many widgets.”

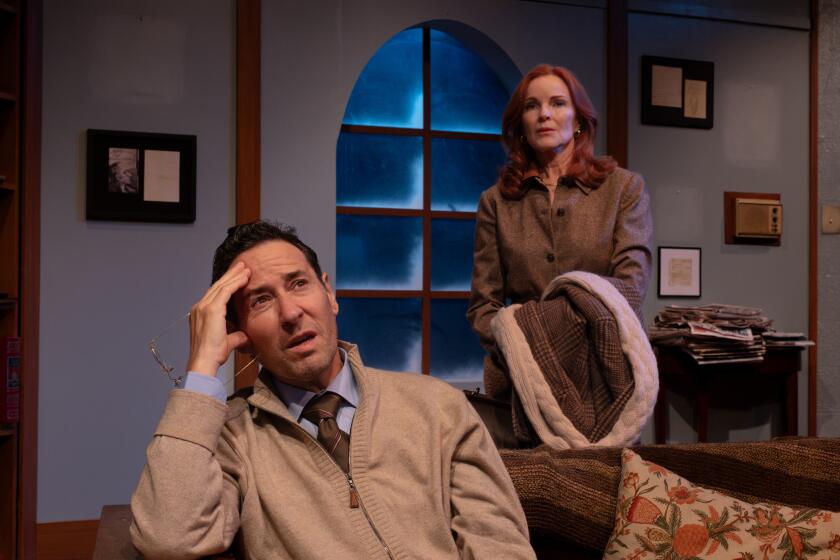

On display are three large black-and-white prints from Longo’s signature “Men in the Cities” series, circa 1980. Grimacing yuppies, dressed in constrictive office wear, writhe and twist in painfully unnatural positions. The question has always been what invisible force causes their tortured contortions and makes them appear like marionettes.

*

The works symbolize “the individual out of balance,” said Earls-Solari, adding that societal malaise may not have been uppermost in the mind of every artist in the exhibit.

“One of the things about looking at art is that you bring to it your own viewing history,” she said. “There are themes in some of the works that were not threatening in 1982 or 1987 but can be viewed that way today.

“This isn’t necessarily a show that will make people laugh,” she said. “But it might prompt reflection and make people look at their own feelings about this.”

* “Anxiety: Views of Contemporary Life” runs through Oct. 14 at the BankAmerica Gallery, 555 Anton Blvd., 4055, Costa Mesa. Gallery hours: Monday through Friday, 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Free. (714) 433-6000.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.