COLUMN ONE : Coliseum Stays in the Game : Officials turn a catastrophe into a catalyst, using FEMA quake funds to keep the Raiders out of the stadium shopping derby--at least for a year.

After January’s earthquake caused extensive damage to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the first challenge was to save the historic structure, to shore up its ivy-covered walls before an aftershock collapsed the stadium.

But a second challenge for Coliseum officials was no less formidable--to keep the Raiders.

To do that they would have to survive another round in the Stadium Game, the frenzied competition among cities to lure sports teams--while the teams maneuver to get the best deals.

Even before the quake, the Raiders had been threatening to move, frustrated by years of unfulfilled promises to upgrade the 71-year-old Coliseum and add luxury suites, the feature essential to peak profitability in pro football today.

After the quake, “I didn’t have to be clairvoyant to expect other cities to be talking to the Raiders,” said Don C. Webb, the man hired to oversee the repairs. “If there ever was an ideal opportunity to take the money and cut and run, it would have been this year.”

In the end, however, it was the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission that turned catastrophe into opportunity and kept the Raiders in the fold--at least for another season.

The team and its “Just Win, Baby” owner, Al Davis, will take the field Sunday in a substantially improved stadium, thanks to commitments of $60 million in federal and state quake funds.

Seven months of round-the-clock construction produced new electrical systems and concession stands and modern restrooms. And, perhaps most significant, quietly included in the project were foundations for the suites long sought by the Raiders.

“If we don’t build the boxes,” said Coliseum Commissioner Sheldon Sloan, “that stadium will die.”

The problem was, the commission had never been able to finance such a project, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which would pay for earthquake repairs, prohibits betterment of a facility with taxpayers’ funds--much as a homeowner is not supposed to use a disaster grant to add a new deck to a house.

“It was a political dilemma,” said former Commissioner Steve Silberman. “No politician wants to be credited with giving the store away to a for-profit, privately held organization (like) a football, baseball or basketball team. At the same time, they don’t want that finger pointed at them as having driven the team away.”

The answer? Take a first step by incorporating the foundations for the suites almost invisibly within the earthquake repair project, itself billed as nothing less than a symbol of renewal for a battered Los Angeles.

So when imposing concrete-and-steel beams were erected around the Coliseum to brace it against future temblors, some were built even stronger to create “one hellacious frame,” in the words of the prime contractor--just right to support “future construction.”

Or as sports investment analyst Paul Much put it: “The earthquake was devastating to Southern California, but it may be a blessing in disguise for Al Davis. The silver lining in the cloud is that he’s going to get his sky boxes.”

‘A Sports Soap Opera’

You don’t have to go far to get a front row seat for the Stadium Game. In Southern California, it embroils virtually every professional sports team and venue: The Rams are set to leave Anaheim Stadium, and the Angels are grousing about the place too. The Clippers are toying with leaving the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, while the Lakers and Kings are looking at rebuilding on the site of the Forum in Inglewood--or moving as well.

Meanwhile, the Pond in Anaheim is trying to lure a second team to join the Mighty Ducks, while San Diego considers a new arena to woo a basketball team, having lost two in the past.

Although the game is intense now, the history of the Coliseum is a reminder that communities have long debated the use of tax dollars on sports facilities--and teams have long shopped for the best deal.

In 1920, voters rejected a $900,000 bond measure for a sports complex in Exposition Park, forcing city fathers to arrange financing from 14 banks. To further reassure taxpayers, the Coliseum was required to be self-supporting, managed by a commission of nine state, city and county appointees.

The stadium quickly became a hub of sports glory. Crowds of 100,000 watched the 1932 Olympics and marveled at the landmark peristyle, which evoked ancient arenas. For football, it hosted not only neighboring USC but also--for 52 years--rival UCLA. When big-league pro sports moved West, the Coliseum was a prime beneficiary: The Rams came from Cleveland in 1946, and the Dodgers used it as a temporary home after leaving Brooklyn in 1958.

But the Dodgers finished their own stadium in 1962 and the Rams packed up in 1980, complaining of outdated seats and other problems. The Rams headed to Orange County for what was then a state-of-the-art Anaheim Stadium.

In May, the Rams paid $2 million to exercise an escape clause in their lease, complaining that that stadium is now outdated.

“You can take the most beautiful structure in the world (and) new innovations make it obsolete,” said Jerry Buss, the Lakers’ majority owner. “The new ones of today are the old ones of tomorrow.”

Buss sees this in his own Forum. Touted in 1967 as “one of the fine buildings erected during the 20th Century,” it is considered small and lacking (no suites).

At the same time, proposals for $200-million arenas are sprouting all over, four for Downtown alone, as their backers scramble to sign up the Lakers, Kings and Clippers.

It’s “kind of a sports soap opera,” Buss said. “I love it.”

Of course, Buss is a world-class poker player, adept at games where “you have a few chips and use them to your advantage.” And occasionally, “you try to bluff.”

But few believe that the Rams are bluffing as they weigh offers from Baltimore and St. Louis. Although the team has had four losing seasons in a row, these suitors seem to view any National Football League franchise as vital to their civic identity, proof of first-rank status.

Baltimore, which lost the Colts to Indianapolis in 1984, is offering to build a $160-million stadium with lottery-backed bonds. St. Louis, which lost the Cardinals to Phoenix in 1988, proposes a $260-million domed beauty. The Rams also have a wish list that includes payment of $30 million they owe for Anaheim Stadium improvements and a lease giving them all stadium revenue, including concessions and advertising.

At Anaheim Stadium, by contrast, they pay up to $400,000 rent each year and split concessions revenue with the city.

“I told (the Rams) that we were prepared for them to ask for the moon,” St. Louis County Executive George (Buzz) Westfall said.

Still, how do you compete with the moon? It is nearly impossible for Anaheim Stadium, and it has 113 “sky boxes,” albeit old ones.

The Coliseum has none of the glassed-in suites that cater to the corporate set, each offering a dozen seats, kitchenette-bars, private bathrooms and waiters on call.

The Coliseum, in fact, is one of two NFL stadiums without them. The other, RFK Stadium, is in the process of losing its team, the Washington Redskins.

In football in particular, “suites are sweet,” as the saying goes.

The reason is the economic structure of the NFL. The largest source of income--the league’s $1.58-billion Fox television contract--is divided equally among the 28 teams.

So is the take from licensing team names for T-shirts and other paraphernalia. Although Raiders’ gear is much more popular than other teams’, Davis does not get a penny more than anyone else.

The only way to get an economic edge on other teams is to maximize the “revenue streams” that vary from site to site, such as parking and concessions--and the suites that lease for $100,000 a year or more, all of which generally goes to the team.

Thus when Webb evaluated what the Coliseum had to offer, his sobering estimate was that “the Raiders start off with a $10- or $15-million disadvantage.”

He did not expect Davis, of all people, to endure that for long.

Davis had fought the NFL to win greater mobility for teams and move his from Oakland to larger Los Angeles in 1982. He flirted with Irwindale and came away with $10 million when the tiny city could not turn a gravel pit into a stadium. He tried returning to Oakland when he could not get suites in Los Angeles, then received new promises at the Coliseum--but little more.

Then the quake shook everything up. Again.

Reacting to the Quake

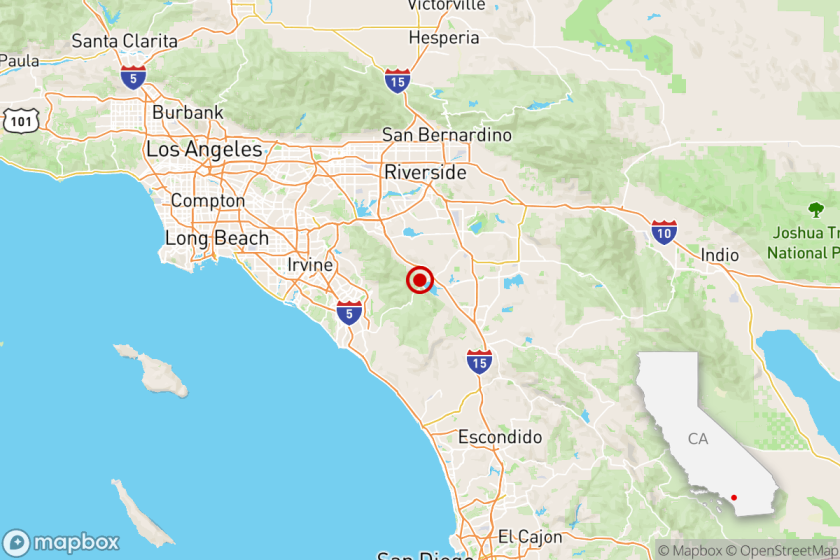

Webb was the logical first person to call early Jan. 17 when a workman discovered that ripples from the Northridge earthquake had packed a punch 20 miles away.

A straight-arrow former college miler trained in environmental engineering, he had come to Los Angeles with Spectacor Corp., which took over management of the Coliseum and in 1991 proposed a $175-million reconstruction, including 282 suites, but was unable to pull it off. Webb, 43, stayed on when the commission hired him to supervise the much smaller project that did go through: a $15-million lowering of the field and reconfiguring of seats to create a more intimate football setting.

That job was being finished when the quake snapped columns four feet in diameter, buckled walkways, turned the peristyle into a latticework of cracks and left the Olympic torch teetering.

Webb called construction executive Ron Tutor. His giant Tutor-Saliba Corp. was handling the $15-million renovation and had been poised for a decade to put in suites, if money ever came through. Tutor, an avid USC alumnus, also had a passion for the Coliseum.

Without a guarantee of repayment, Tutor moved in construction crews and heavy equipment to support the walls. “I was genuinely afraid (that) major portions could come down,” he said.

Soon after, the commission rewarded him with a no-bid contract to carry out the full repairs, limiting overhead and profit to 3.5% of the total. Tutor vowed to have the place ready for USC’s Sept. 3 opener or, “I’m leaving town.”

Also keeping an eye out for USC was the commission’s vice president, Los Angeles City Council President John Ferraro, a former All-American there. He quipped that Tutor would wind up buried in the Coliseum’s concrete “if he doesn’t get it done.”

To Los Angeles County Supervisor Yvonne Brathwaite Burke, the pressing issue was the impact on economically depressed South-Central Los Angeles. “The Coliseum became symbolic, as did the 10 Freeway, that this was not just a Valley earthquake,” said Burke, the commission’s president.

Time and again, she would speak of the 8,000 jobs provided by the Coliseum complex, even if virtually all were part time--in the parking lots or hot dog stands--and the potential for minority hiring in any reconstruction project.

Such considerations also could sell a project in the political arena. James Lee Witt, national director of FEMA, received a 1991 study estimating $100 million in economic benefits from the Coliseum through a “multiplier effect” that calculated every conceivable dollar spent in restaurants, motels and the like--even players’ salaries.

Equally important was White House aide John Emerson, who had run President Clinton’s California campaign and was coordinating Administration response to the quake. Emerson said: “The President of the United States cares about getting Los Angeles on its feet,” and although damaged hospitals and schools had priority, “a lot of people see the Coliseum as a symbol of Los Angeles.”

Federal authorities quickly approved use of FEMA funds to pay 90% (the state would pay the rest) of a Coliseum repair project initially estimated at $33 million.

But through the rah-rahing for USC and high rhetoric about symbols of renewal, others had their eye on the nitty-gritty question that, in their view, would determine the Coliseum’s long-term fate: Would the Raiders stay?

They believed the stadium would never be viable with only college football, even adding an occasional rock concert, motocross event or religious rally.

Yet the Raiders were operating on year-to-year agreements. Now, with the Coliseum’s status uncertain, the team had no choice but to scout alternatives for the fall--an ominous fact to some.

Said Silberman, who recently left the commission for the city Board of Pension Commissioners: “Many of us believed if you lose them for a season, you lose them.”

Misery and Profit

Oakland’s letter to Al Davis was in the mail--the fax machine, actually--Feb. 2.

“We don’t want to profit from someone’s misery,” insisted Alameda County Supervisor Don Perata. But, well, you know, the Oakland Coliseum was available.

One of the quirks of the Stadium Game is how communities that once lost teams fight the hardest, later on, to get a new one--or their old team back. Like some spurned lovers, they’re willing to kiss and make up. And fork out.

In the eyes of Oakland officials, scarred veterans of the game, Los Angeles was primed to lose the Raiders because it had so many attractions--beaches, theaters, other teams--that it did not have the same emotional stake as smaller burgs in meeting Davis’ price. They recalled Councilman Nate Holden once saying: “Let him go. L.A.’s the place, and if he doesn’t want to be here, get out.”

“You got to remember, almost every owner has a pretty big ego,” said George Vukasin, chairman of Oakland’s Coliseum Commission.

“I know Al, and (after the quake) I said: ‘Al, can we help you?’ ”

By the time this round in the Stadium Game was over, Raiders’ attorney Amy Trask would also thank Baltimore, Memphis, Orlando and Hartford “for the magnificent alternatives they afforded us.”

Behind the Scenes

For someone who has owned several teams, Harry Ornest keeps a low public profile. But the 71-year-old former boss of hockey’s St. Louis Blues and the Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonauts remains a behind-the-scenes player in finance and sports as vice chairman of Hollywood Park, where racing czar R.D. Hubbard has been expanding like mad.

They have added a huge card “casino” beside the horse track and plan a music hall on the sprawling Inglewood property. So it was not surprising that Ornest hinted at new possibilities when he ran into Ferraro earlier this year.

As an avid free-enterpriser, Ornest was enraged that the government was spending nearly $50 million--the figure had risen by then--to fix the Coliseum. He liked to quote Times’ columnist Jim Murray, who called it “that rotting pile of urine-stenched old stones.”

Ornest said Ferraro told him: “We need a place to play.”

“I said: ‘Can you picture a new stadium that would house USC, UCLA and the Raiders all in one?’ ”

Ornest was hinting at a stadium on Hollywood Park grounds, just floating an idea.

But Ferraro shrugged, he said. “(He) said: ‘Harry, we couldn’t have gotten that $45 million if it wasn’t for the earthquake.’ ”

Getting the Job Done

“The Coliseum Commission has not always delivered,” acknowledged Burke, its president. “(The Raiders) wanted to see something in terms of good faith . . . some sign.”

The most basic sign was showing that the job could be done in time. But that would take a near-miracle, even with 800 workers and a 24-hour schedule. For the bureaucratic hurdles were daunting: FEMA rules, fire codes, city building codes and--because the Coliseum is a national historic landmark--preservationist concerns.

After San Francisco City Hall was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, federal aid was held up more than four years amid squabbling over such matters.

Four months could lose the Raiders. Yet the project threatened to be stalled when preservation groups could not agree on what should be saved at the Coliseum.

Was a press box installed in the 1950s part of its historic fabric? Ivy on the walls? How about the long trough urinals in the men’s rooms?

Those eager to inch the stadium closer to state-of-the-art believed it essential to overhaul the bathrooms and set aside more for women--reflecting the modern reality of who goes to games. But some hard-line preservationists insisted that the troughs stay.

“I’m boggled by it,” said Linda Dishman, executive director of the Los Angeles Conservancy, which did not insist on the troughs.

One Sacramento-based preservationist called his Los Angeles counterparts “sellouts.” A Los Angeles leader became suspicious, in turn, that “looney tune” Northern Californians wanted to obstruct the project because they were “ticked off that L.A. is getting all this FEMA money.”

In the end, they compromised: The troughs could go. The ivy too. But thousands of cracks would be repaired--using space-age epoxy--so the concrete looked little different than when it was poured decades ago. Lighting in the pedestrian tunnels would use modern fixtures that looked vintage.

Improvements such as those had FEMA’s approval. With major projects, the agency requires that the structure be brought up to modern standards. Whether funds go to repair apartments or a public facility such as the Coliseum, “the more we can do to build safer and better,” director Witt noted, “. . . will save federal, state and local tax dollars in the future.”

Because the Coliseum power system did not meet current codes, it got a new one--with 247 miles of electrical lines. The damaged video board that shows instant replays? Why not ask for the latest “Diamond Vision” version, which could be billed as “the largest stadium screen in the nation?” FEMA said OK.

And speaking of big, how about those “seismic reinforcing beams” and piles to protect the entire structure against quakes; 56 beams would ring the stadium and the piles would be buried as deep as 92 feet into the ground.

They were a major reason project officials calculated that they used enough concrete to fill 13 feet above the football field, and 7.6 million pounds of steel rebar.

And so it was that one sports executive gestured up at the imposing supports one day and asked: “Wouldn’t it be amazing, simply amazing, if some of those were being built with a little extra concrete, and right in the spots they would be needed to support”--a wink--”oh, say, luxury suites?”

Who Will Pay?

Virtually everyone in the Coliseum project agrees that it made no sense to build the frame differently: to put in only what was needed for earthquake support, then have to tear much of it up for more bracing--perhaps this winter--after a deal goes through to add heavy rows of suites.

“Not to do it now would be extremely illogical and foolish,” Tutor said. “It’s upfront. . . . This design has a certain number of larger piles and foundations. . . . I can only say the obvious: . . . (It) does allow for sky boxes.”

The minutes of commission meetings since the earthquake, however, contain no mention of the matter, or what officials agree became the main issue: Who would pay for the extra work? But it was discussed at executive sessions and less formal gatherings.

“I don’t think anyone said, ‘You sneaky little devils, you, you’re trying to sneak stuff in,’ ” recalled Dishman. “(But) the way it was left in our meetings, it was unclear how much (FEMA) would pay for.”

Robert Mackensen, director of the state Historical Building Safety Board, said he was led to believe that FEMA would only pay for “what is needed to support the Coliseum,” not extra work to facilitate suites. “If it was you or me, they’d say: ‘What are you up to, pal?’ ”

Indeed, FEMA’s regional coordinator, Frank Kishton, agreed that there were some improvements “that the commission and everyone knows were not eligible . . . the enlarged caissons, for example.”

But Kishton also recalled the pressure from Washington on down to get the job done--and said he was uncertain how the money question finally was resolved.

“It’s always conceivable,” he noted, “that an auditor down the road . . . says, ‘Geez FEMA, you made a mistake with that.’ ”

In fact, according to a variety of project officials, all work to date has been declared “FEMA eligible,” meaning it will be funded.

They walk a rhetorical tightrope in explaining why.

Webb said: “We have to be careful because we’re using public funds. . . . But we don’t want to paint ourselves into a corner--so that framing restoration and repair and strengthening we’re doing now isn’t done in such a way that keeps a future suite program from happening, for instance.

“I want to be careful how I characterize this because to the extent that we’re bettering something that didn’t need to be done, the commission stands the possibility of paying for that.”

“I just want to be clear,” he concluded. “It’s a betterment that’s necessitated by the earthquake.”

Commissioner Sloan similarly said it was “coincidental” that the seismic upgrading may “ultimately lower the cost of the boxes.”

How much could be saved?

“They now have an opportunity to cut $25 million off the price,” one sports official said at last week’s ceremony reopening the Coliseum.

“It will enable them to do it for maybe $25 (to $30) million, and get the suites without missing a season. Isn’t that what the Raiders have been looking for all along?”

Raiders Get a Deal

The Raiders would not say what convinced them to stay put for now. Not unusual in the secretive realm of Al Davis, team officials declined comment.

On June 22, they signed an agreement to play the 1994 season at a Coliseum that Webb promised would be “safe for everybody but the opposing teams.”

Whereas the Raiders had been paying about $800,000 rent, they will play rent-free this year--unless a long-term agreement is negotiated including construction of boxes and other renovation of Exposition Park. The rent then could be paid retroactively to help secure bonds or a loan to complete the work before the 1995 season.

In July, Burke and Webb traveled to Washington to inform federal authorities that repair costs at the Coliseum could approach $60 million. Go ahead, they were told.

Today, even as life--and football--return to the Coliseum, there are many issues unresolved. The seating and the bowl shape still mean long walks to concessions. Parking remains inadequate by NFL standards and revenue from it still goes mostly to the state--not the team, as elsewhere. And, of course, the project will not stop others from wooing Davis.

“They can do anything they want to and at a whim he can take that team away,” said Dan Visnich, a preservationist on the staff of state Sen. Nicholas C. Petris, a Democrat from . . . Oakland.

“All they want to do is please Al Davis, and I’m not certain he’s a person who can be pleased.”

What’s more, he’s not the only tenant that the commission must worry about. With three years left on their lease, the Clippers are weighing alternatives to the Sports Arena. Too small. No suites.

The executive vice president of that team, Andy Roeser, noted with amazement that the quake left the Clippers’ home with relatively trivial damage. Of course, he wasn’t sure that was a good thing in this crazy Stadium Game.

“As you can see from the extensive work going on at the Coliseum,” Roeser said, “it perhaps would have been a blessing . . . had the earthquake struck 200 yards east”--meaning under his team’s Sports Arena.

Playing the Want Ad Game

Team executives, entrepreneurs and government officials are playing “Let’s Make a Deal” all around the country, but nowhere more feverishly than in Southern California. What are the area’s sports teams after? Who is trying to lure them away? This hypothetical classified section offers a look.

TEAMS LOOKING TO UPGRADE

L.A. Rams

NFL franchise seeking new home after exercising “escape clause” at Anaheim Stadium. Hoping the turf is greener on the other side . . . of the country. Willingness to build new facility a plus. No, make that a must. Oh, and we don’t want to pay rent. Call Georgia Frontiere.

L.A. Lakers and Kings

Looking for larger, modern-day arena worthy of “Showtime” and “the Great One.” Could be built on the parking lot of our current home, the Forum in Inglewood, but right arena and deal could get one or both of us.

L.A. Clippers

With only three years left on lease at aging Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena, basketball team ready to ACT NOW to find new home FIRST--and maybe beat the Lakers at something.

$$$ Suite Deal $$$

Looking for the right package of luxury suites. Write Mr. A. Davis, L.A. Raiders, Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. (Will be here at least this season after $60 million in earthquake repairs.)

SEEKING TENANTS

Downtown Los Angeles

Four sites for possible $200-million arena, and armies of office workers ready to stay after dark for the right entertainment . . . like basketball and hockey games. Might take one team--but prefer two--to pay the bills. The extras: oodles of luxury suites. Come see for yourself.

City of Anaheim

* We Still Have Georgia’s Rams in Our Minds *

We’ll spruce up Anaheim Stadium just for you. Really. Why, we’ve already ordered a feasibility study to see how we can avoid losing the Angels as well when their lease runs out in a few more years. So wing it to city of Anaheim, where you can look at what we’ve done at the . . .

Anaheim Pond

* You want state-of-the-art? *

We ain’t quacks--just ask the Mighty Ducks, our hockey team from Disney. Or ask Barbra, who sang here, or the Clippers, who are playing seven games. Just want one more full-time tenant.

Hollywood Park

We’ve added a lavish card room (er, CASINO) to famed racetrack and wouldn’t mind expanding into sports. We’re BIG THINKERS (between us, had Al Davis out to visit) and wouldn’t mind luring the college boys to a new football stadium as well. Place your bets with R.D. Hubbard.

San Diego

Sure we lost two basketball teams--the Rockets and Clippers--but maybe plans for a $156-million private-public arena will bring back the NBA, and why not hockey too? Meanwhile, we’ll pray that the Padres stay at San Diego-Jack Murphy Stadium (the baseball team is for sale) while we say thanks for the football Chargers, who actually seem to like it in a “small media” market.

TEAMS WANTED ELSEWHERE

City of Baltimore

* We won’t butt heads with you, Rams! *

Drool over this beautiful Maryland estate, a $160-million stadium paid for by lottery-backed bonds. And you wanna deal? Try no rent--and you get to keep all the revenue from tickets, suites, parking and concessions.

City of St. Louis

Does Baltimore have a dome? If you’re the Rams, or other NFL team, we’ll give you one, atop a new stadium, worth $260 million.

* Come Back to Oakland *

The Raiders loved us and left us, but to show we’re not bitter . . . Come back, Al.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.