Britain Ends Broadcast Ban on Irish Extremists : Negotiations: Prime Minister Major also backs referendum on Northern Ireland’s fate. Both moves indicate desire to move ahead on peace plan.

- Share via

LONDON — Prime Minister John Major ended a much-ridiculed ban on broadcasting the voices of extremist leaders in Northern Ireland on Friday and declared his support for a referendum of Catholics and Protestants to determine their political fate.

Major’s comments, during a visit to Belfast, constituted his strongest signal yet that he is prepared to make progress on negotiations among the contending Protestant and Catholic forces in the deadly 25-year-old Northern Ireland conflict even though he has not received an explicit guarantee that a recently declared Irish Republican Army cease-fire is permanent.

The government also further reduced security measures in Northern Ireland, agreeing to open a number of roads connecting the British-ruled province with the independent Republic of Ireland. British security forces had erected concrete barricades along hundreds of the rural roads in an effort to deny easy cross-border movement to terrorists and their materiel.

The lifting of the broadcast ban appeared primarily intended to encourage more peace overtures from Catholic republicans, while the vow of support for a referendum was an attempt to allay the fears of Protestant unionists.

The ban on broadcasting the voices of both Catholic and Protestant paramilitaries has been the source of much derision and mostly affects Gerry Adams, leader of the outlawed IRA’s legal political wing, Sinn Fein. While Adams’ face is regularly seen on British television, his voice is dubbed by an actor who merely repeats Adams’ words, sometimes in less than perfect synchronization.

“The broadcasting restrictions were brought in to stop supporters of terrorist organizations from using television and radio to justify violence,” Major said. “I believe the restrictions are no longer serving the purpose for which they were intended. . . . Ways have been found to circumvent them. But most importantly, we are now in very different circumstances.”

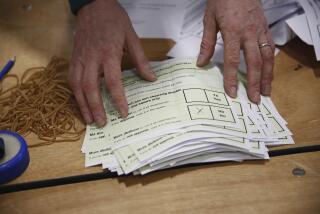

The IRA, the group battling for unification of Northern Ireland with predominantly Catholic Ireland, declared a cease-fire Aug. 31 in response to proposals for peace talks jointly sponsored by the governments in London and Dublin. Major has said he would be ready to begin talks only when the IRA or Sinn Fein states unequivocally that the days of guns and bombs are gone forever.

Neither has done so publicly, though the IRA has not committed any act of terrorism since its declaration. The same is not true of its extremist Protestant counterparts, who have staged several bombings since Aug. 31.

The promise of a referendum on any settlement reached around the negotiating table was meant to reassure Protestants that they will not be separated from Britain against their will, according to many observers.

Since they are now a majority in Northern Ireland, the Protestants could presumably block the outcome the nationalists say they are still seeking: unification with Ireland.

Many Protestants say they believe that a “secret deal” exists between Dublin and London that will force them into what they consider an odious fate.

“Let me say to all the people of Northern Ireland,” Major said, “the referendum means that it will be your choice whether to accept the outcome” of any negotiations.

The opening of the border roads was a significant concession to Catholic nationalists, many of whom believe that free movement across the borders means a de facto unification with Ireland, if not constitutional merger.

Activists have been playing a cat-and-mouse game with British security forces for several weeks, bulldozing border blockades by day only to have them replaced by the British overnight.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.