POP/ROCK : RICHER THAN VELVET : Don’t Worry About John Cale Eating Regularly; He’s Got Plenty on His Plate

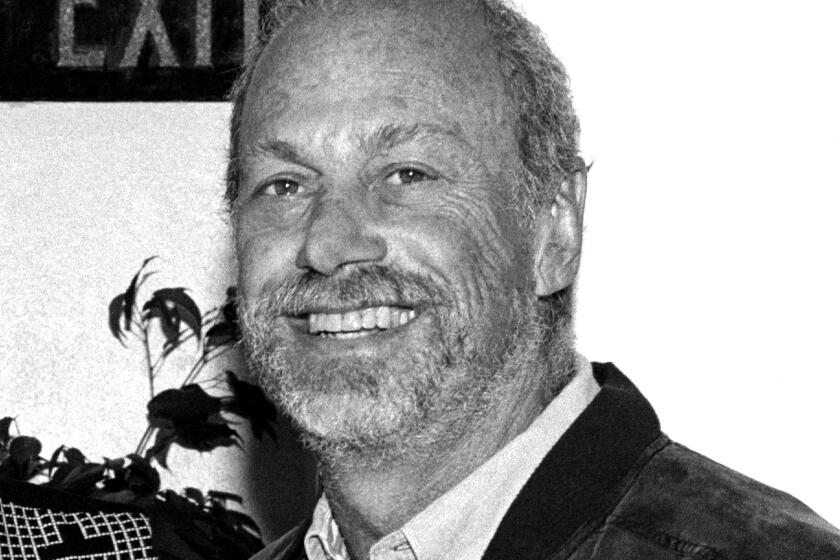

Few rock musicians have pursued an agenda as diverse as John Cale’s.

His hugely influential first band, the Velvet Underground, was marginal in its time (1965-70) but since has become a rock-cultural monument. The Velvets are recognized as the cornerstone of the “alternative” rock movement that, shockingly, has come to occupy a penthouse suite in the commercial edifice of ‘90s pop.

While Lou Reed, the Velvets’ singer and songwriter, expanded rock’s thematic possibilities by casting a witty or coldly journalistic eye on life in the urban underbelly, Cale played an important part in the band’s sonic inventions. With Cale on viola, bass and keyboards, the band from New York City upped the ante on how assaultive, dissonant and challenging to an audience rock could be.

Its agenda was more open than those of many of its ‘90s heirs--the Velvets could turn a gentle ballad with the best of them, and the throbbing mania that Cale helped whip up on such songs as “White Light/White Heat” and “Sister Ray” was balanced by the stark, stately cast of his viola playing on “Heroin.”

He left the Velvet Underground in 1968 after playing on the band’s first two albums. In 1970 he launched a career of his own that has covered a wide swath of stylistic territory, proceeding in a zigzag fashion virtually guaranteed to limit his following to a cult.

His early university training in London, and a summer of 1963 fellowship at Tanglewood in Massachusetts, grounded him in classical music and avant-garde composition. Those strands have surfaced repeatedly to color such pop-oriented albums as “Paris 1919” (1973) and “Last Day on Earth,” his recent collaboration with folk-based singer-songwriter Bob Neuwirth.

At other times, on “The Academy in Peril” (1972) and “Words for the Dying” (1989), an album built around a suite of symphonic settings of Dylan Thomas poems, the classical or avant-garde influences have dominated.

Along the way, Cale has proven himself both a master of elegant pop craft and a mad wreaker of rock-as-mayhem. His first two albums of pop songs, “Vintage Violence” and “Paris 1919,” still stand as highlights of early-’70s rock with their emphasis on tempered, roots-accented music and graceful balladry.

In the mid-’70s, he turned mean (or at least his lyrical personae did) and churned out raw, stripped down, attitude-filled rock ‘n’ roll albums widely acknowledged to have helped set the stage for England’s punk revolution of 1976.

As the producer of debut albums by the Stooges, the Modern Lovers and Patti Smith--all of them punk precursors in their own right--he served as a flame-fanner for the underground rock movement that first had flickered with the Velvets.

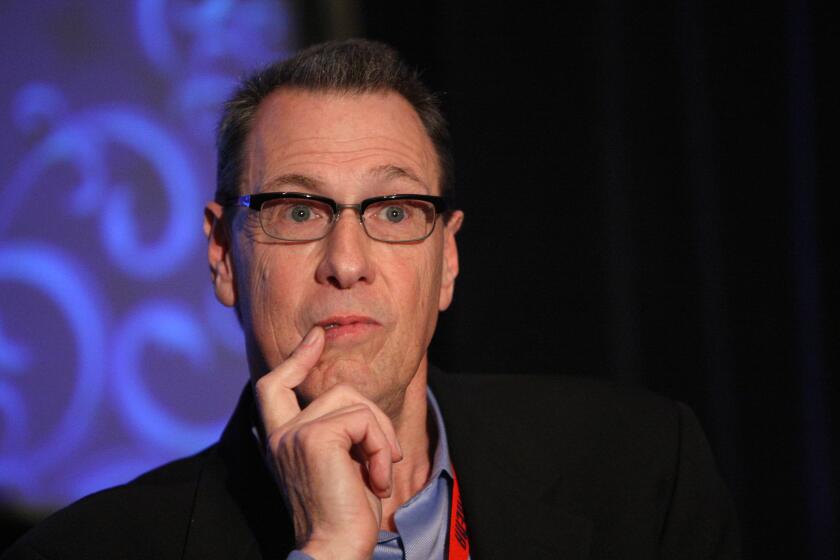

Now, at 52, his musical agenda is as full and varied as ever.

Last spring saw the release of “Last Day on Earth,” an enigmatic but frequently alluring cycle of songs and dialogue with a satiric or philosophical thrust and too many stylistic strands to catalogue briefly. Cale and Neuwirth toured together in Europe after its release, fronting an unlikely ensemble that included a string quartet, gospel singers and a pedal steel guitar.

In a recent phone interview from his apartment in Manhattan, Cale sounded at ease and fully self-possessed as he chatted in a speaking voice that, like his singing baritone, is full of his native South Wales. Not everybody would come across as calmly, given the assortment of current assignments that Cale is juggling.

In the works are a musical theater piece based on the Orpheus myth (including parts for a barbershop quartet) and an opera inspired by the life of Mata Hari, which Cale is pushing to finish in time for a December debut in Vienna. He also is putting the last touches on the score to a Spanish feature film based on one of his songs, “Antarctica Starts Here.” Meanwhile, he is thinking about recording another album early next year, perhaps integrating rock band with string quartet.

With all that going, he will squeeze in a brief tour (including a show Monday at the Coach House) to draw attention to Rhino Records’ recent release of “John Cale: Seducing Down the Door,” a two-disc, 38-song overview of his post-Velvets career from 1970 to 1990. The tour finds him performing solo, as he has for most of his concerts since the mid-1980s.

The only musical possibility that he has crossed off his agenda--permanently, he believes--is anything having to do with Lou Reed.

While his tone remained even, Cale’s words were bitter when the subject of the Velvet Underground’s 1993 reunion tour of Europe came up. In his eyes, the reunion, which yielded the album “The Velvet Underground Live MCMXCIII,” was diminished by a surfeit of control on Reed’s part and a paucity of the experimental, improvisational playing that the band strived to achieve during its initial run.

“I’m disappointed that we didn’t get to do what we said we were going to do, which was come up with a lot of new material,” Cale said. “I don’t have anything against (the Velvets’ old songs), but they were a barrier to doing anything new and creative. We were so adamant about doing new material when we first met. How it wound up, it’s a shame.”

He said “Coyote,” the one new song to emerge on the album, began as an improvisation between him and Reed but “by the time it came out it was so contained and disciplined that it had lost its magic.”

The Velvets had planned an “MTV Unplugged” session and to tour the United States but, Cale said, the band unraveled after Reed demanded what Cale considered excessive control over the MTV performance.

“He wanted to produce, he wanted his own engineer. It was a matter of control, a daily dose of it (that) really got to everybody on the tour after a while. I think everybody said, ‘I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more.’

“The quality of the business decisions alone was very poor,” Cale added. “It was a matter of personal embarrassment for me that I wasn’t able to affect the situation, to make it work better than it did.

“But looking back, I don’t think there’s anything anyone could have done. The situation was preordained from the beginning. I made the mistake of thinking things had changed. They hadn’t. The things that happened were so similar to the things that happened in ’69. The same exact problems, handled in the exact same way, as if no one had learned anything.”

He said it is unlikely that he ever will work with Reed again. “I would doubt very seriously that any change is possible, and even if it was possible, it’s a question of trust. I’ve been down that road with ‘Drella’ (‘Songs for Drella,’ the 1990 album that Reed and Cale recorded as a duo in tribute to the Velvets’ early mentor, Andy Warhol) and with the live album and the tour, and it seems like 1969 all over again. Life’s too short.”

He did point dryly to one positive result of the Velvet Underground reunion: “It was valuable in that it got me irate enough to get on with a lot of work.”

There is a chance, however, of a happier reverberation. During the interview, Cale used his call waiting to hop to another phone line to confirm details for an imminent recording session in which he would be joined by the two other original members of the Velvet Underground, guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen (Moe) Tucker.

Rounding out the studio band would be Chris Spedding, the excellent English guitarist who backed Cale on some of the most memorable songs of his darkly aggressive, pre-punk mid-’70s period, and bassist Eric Sanko, formerly of the Lounge Lizards.

Cale said the group’s immediate agenda is to record the three new rock songs he has written for the Spanish film of “Antarctica Starts Here.” If he likes the results, he may keep the band together for additional recording early next year.

“That rhythm section is a very strong group,” he said. “I didn’t want to see Moe and Sterling disappear” in the wake of the Velvets’ reunion. “It’s worth a go to see if there’s an afterlife here.”

On paper, the lineup looks like a throwback to the all-star bands Cale commanded in the ‘70s when he worked with members of Little Feat (on “Paris 1919”) and Roxy Music (on “Fear,” “Slow Dazzle” and “Helen of Troy”). Given the presence of Morrison, Tucker and Spedding, fans of Cale’s mid-’70s work can well imagine a return to the jabbing, thrusting, hard-edged attack of that era.

It has been 15 years since he last presided over a raw, cranking album of full-on rock songs, the satisfyingly primitive “Sabotage/Live.” Given recent marketplace preferences for dark, angry, aggressive rock, revisiting that era might be the commercially savvy thing for him to do.

However, when asked about the prospect of gaining a wider audience by going back to those brutal days of 1974 to ‘79, he said he’s “not persuaded that’s possible. Those were things that were done then for whatever reason. I don’t feel the urge to do that.”

Some of the highlights from that period would have fit comfortably (if that’s not an inappropriate word in this context) on the soundtrack to “Natural Born Killers.” In songs like “Guts” and “Leaving It Up to You,” Cale played a killer’s part himself.

In “Guts,” a song laced with gore and scatology and revved by a savage, anthem-like riff, the cuckolded protagonist avenges himself with a shotgun blast. But as rage dissipates, self-disgust sets in, and with it the realization that “the waster and the wasted get to look like one another in the end.”

“Leaving It Up to You” makes Nine Inch Nails look like a kiddie show, while anticipating Oliver Stone’s “Natural Born Killers” thesis about people grown so brutish and brutalized that they murder for the kicks and the attention. (And Cale’s character, unlike Stone’s, is not a cartoon; he has some idea of the enormity of the destruction he contemplates.)

In a memorable rant, Cale captures his protagonist working himself toward some avenging, obliterating act:

“And it’s sordid how life goes on, when I could take you apart. And if you give me half a chance I’d do it now. I’d do it now . Right now, you fascist! I know we could all feel safe like Sharon Tate, or we could give it all up--we could give it all up. And the newspapers, oh the newspapers, they’d be listening to me giving it to you. And the radio, what about the radio? Oh, they’d be listening to me giving it to you. Right, mama. Damn right, mama. “

We should note here that the scariest thing Cale ever recorded actually is a ghoulish, harrowing version of Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.” And that “Helen of Troy,” the same album that offered “Leaving It Up to You,” also featured the pretty, wistful love song, “I Keep a Close Watch.”

Cale said that in those days he would keep a close watch on newspaper crime accounts, clipping out stories that might serve as inspiration.

“I was picking characters and showing them from their one-dimensional point of view and then from a point of view where you got a little glimpse of all the pressures on them, a little more complete view of all the forces that were at work.”

In performance during the mid-’70s, Cale would don a scary get-up of leather jacket, shades, ski goggles and hockey mask to theatricalize some of these extreme songs. The theatrics, he said, were unpredictable and helped keep his touring band from falling into a dulling routine. But the costumery also was a way of “keeping a respectful distance from my subject matter,” and reminding himself and his audience that it was, after all, an act.

The live chicken that Cale brought on stage for a show in London, circa 1977, didn’t benefit from any such buffer of sanity. Cale sacrificed it in a voodoo-like rite. Unlike Ozzy Osbourne and his infamous head-chomping of a bat he thought was a toy, Cale knew exactly what he was doing.

In “Beyond the Velvet Underground,” a book compiling the public musings of the various band alumni, Cale recalled the episode: “I cut a chicken’s head off on stage. A whole bunch of people (in the band) walked off. They were all vegetarians. They wanted to know before it happened, ‘What are you gonna do, are you going to hurt it?’ I said, ‘No,’ and afterward they told me I lied to them. I said, ‘I didn’t hurt it, I killed it. It didn’t feel a thing.”’

“I think personal catharsis played its role in them,” Cale said of the songs and stage maneuvers in which he took the part of characters creating havoc. “But I don’t think I was at the point of jumping out a window” in his personal life. “I recognize it now for being the straw that broke the camel’s back, but I used to be self-possessed about it. It was a painful exercise, but it got inside those characters.”

Cale turned to quieter, more refined means in the 1980s, although his portraits of characters on the edge remain a staple of his solo shows. “I wanted to stop that kind of gathering swine school of performance where everybody goes running over the precipice and that’s what everyone comes to the show expecting.” Now, he said, “it’s more method acting. There’s a way of getting the same emotion into performance, (yet) being very still. It’s more of a recital ambience than a spectacle.”

Cale’s taste for demonstrative performance limned with violence predates his rock ‘n’ roll days. When he arrived at Tanglewood in 1963 (on a fellowship sponsored by Leonard Bernstein, and for which Cale had been interviewed by Aaron Copland), he already had a reputation for bringing a performance artist’s penchant for acting out to the usually staid world of classical music and modernist composition.

“I think they knew what was in store,” he said. “They sort of drew the line at violent pieces of music before I got there, but they relented about two-thirds of the way through (the summer program) because I kept badgering them about it.” Cale got permission to play a piano piece that involved banging around inside the instrument’s innards. Then he pulled out an ax and started hacking at a table on the stage.

“It sort of sent Mrs. Koussevitzky running out of there in tears,” he recalled, alluding to the widow of Serge Koussevitzky, the famous Boston Symphony conductor who had founded Tanglewood. Other outraged onlookers reacted more aggressively, he says, hurling eggs at the stage (evidently they had some inkling of what Cale was about to do, and smuggled in this optimal ammo). “The guys that threw the eggs came back and apologized,” he said. In any case, he added, they missed.

Cale’s works in progress promise more interesting chapters. The movie version of “Antarctica Starts Here” features Ariadna Gil, one of the stars of “Belle Epoque,” last year’s Academy Award winner as Best Foreign Film, in the role of the downward spiraling actress Cale depicted in his 1973 song.

“I wrote it about ‘Sunset Blvd.’ (imagining) Gloria Swanson. The guys who wrote the film thought more about Edie Sedgwick. But I won’t argue that point. I have fond memories of Edie.” Cale said he appears in the film as himself in a musical performance scene.

His opera-in-progress, “Mata Hari: The Lure of the Vertical,” takes as its heroine the nude dancer and femme fatale who spied for the Germans during World War I before she was caught and executed by a French firing squad. She was granted one of her last wishes: to be allowed to die wearing her trademark black silk stockings.

Cale also is proceeding with a theatrical work called “Life Underwater” that received a preliminary staging at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn, a haven for avant-garde artists that also has housed productions of “Songs for Drella” and “Last Day on Earth.”

“It’s kind of the ‘Reservoir Dogs’ version of (the Greek myth of) Orpheus. It’s pretty violent,” Cale said, detailing a scene played in the dark in which Orpheus, the heavy of the piece, tries to force an abortion on his wife, Eurydice. Cale plays Orpheus’s good brother, Benno. “The story is about transformation, how water is the main transforming element in Benno’s life,” Cale said. “The piece is incomplete; it needs another half hour of songs. I’m meeting with some people next week about presenting it on CD ROM. I don’t know how it’s going to work out. Am I going to be designing a game show, or a Nintendo piece, or what?”

Given some of the extreme subject matter he has broached with his music, one wonders whether Cale was giving a self-assessment in the opening sequence of “Last Day on Earth,” when his character, described only as “A Tourist,” muses: “I drank from a paranoid glass/I come from a paranoid base.”

“I would say it’s ironic,” he demurred.

Another line in the piece asks the aesthetic question: “Who will avoid the undertow of sentimental drift?”

Cale, whose love ballads are as memorable as his outbreaks of paranoia, trusts himself to be sentimental without drifting, a quality essential to his musical diverseness.

“I don’t have any qualms about that. There are different kinds of sentimentality. Some that are fairly spontaneous, and some that are not. I like them spontaneous. I’m Welsh, so I have to allow for it.”

* What: John Cale.

* When: Monday, Oct. 3, at 8 p.m.

* Where: The Coach House, 33157 Camino Capistrano, San Juan Capistrano.

* Whereabouts: Take the San Diego (5) Freeway to the San Juan Creek Road exit and turn left onto Camino Capistrano. The Coach House is in the Esplanade Plaza.

* Wherewithal: $15.

* Where to call: (714) 496-8930.

MORE POP /ROCK

IN SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO: CHRIS GAFFNEY

Gaffney and his band, the Cold Hard Facts, are one of the hardest rocking honky tonk outfits in Southern California. Thursday and Friday, Sept. 29 and 30 from about 9 till last call, they’ll be at the Swallows Inn--one of Southern California’s hardest rocking honky-tonks. (714) 493-3188.

IN CERRITOS: SMOKEY ROBINSON

As the leader of the Miracles and on his own, Robinson has crafted some of the sweetest, smoothest, most shimmering and memorable pop songs of the last thirty years. He’ll be at the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts Friday and Saturday, Sept. 30 and Oct. 1 at 8 p.m. (800) 300-4345.

IN IRVINE: JIMMY BUFFETT

One of pop’s most consistent ticket sellers, he enjoys a loyal following as leader of the Parrot Heads, those party animals who make concerts something of a moveable Margaritaville. He, and they, will be at Irvine Meadows on Friday, Sept. 30 and Saturday, Oct. 1. (714) 740-2000 (Ticketmaster).

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.