Scenes From a Family Gallery : Paul Kantor, his former wife Ulrike and their son Niels have devoted their lives to art in L.A.-- even if the role of art dealer is misunderstood.

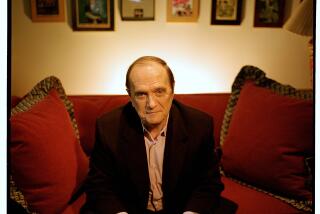

‘There was no art scene when I got here in 1946,” recalls pioneering art dealer Paul Kantor, who was to spend the next 48 years attempting to change that. “I was a 28-year-old kid just out of the Navy, and I got into this business not really intending to.

“It took very little money to open a gallery in the late ‘40s--rent was just a few hundred dollars a month,” says Kantor in an interview at his Beverly Hills home. Also in attendance this afternoon is his former wife, Ulrike Kantor, who had a gallery in the early ‘80s that showcased the young Neo-Expressionist artists of that period, and their son, Niels Kantor, who recently opened a gallery on Melrose. The topic under discussion is the family business.

“There was this place on La Brea, the Fraymart Gallery, that showed young artists, and I loaned them money thinking I was a limited partner,” continues Kantor, who was born in New York City in 1919. “I subsequently discovered I was liable for any debts incurred by my partner, who was running up sizable debts, so we had a settlement and I wound up with a gallery. That’s how I became an art dealer--I got stuck!”

Kantor is being a bit disingenuous here. In fact he had, and has, a great love of art, and had a remarkably adventurous eye early in his career. Credited with discovering Richard Diebenkorn, he also mounted the first Los Angeles exhibitions (in 1952) of Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes and Willem de Kooning. (For two De Kooning exhibitions, Kantor published catalogues with essays by playwrights Clifford Odets and William Inge.)

“Dealing is a rough business and L.A. has never understood how important good dealers are on the high road of cultural life,” says Walter Hopps, who played a seminal role in L.A. art as one of the founders of the avant-garde Ferus Gallery of the 50s, and as director of the Pasadena Museum from 1963-67. “Dealers often do what museums haven’t yet figured out to do, and Paul’s contribution has never been adequately understood or appreciated.

“He brought something to the city that hadn’t existed prior to his going into business, and that something was tough professionalism,” adds Hopps, currently adjunct curator at the Menil Collection in Houston. “What I mean by tough professionalism is that Paul was devoted to creating some kind of permanent life for the art he loved, and knew that the only way to do that was to sell it and sell it profitably--and that’s what he did.” Kantor’s commitment to art is evident in the story of how he came to know Diebenkorn.

“In the early ‘50s, the major local art activity outside of traveling shows was an Annual held every year at LACMA. I first saw Diebenkorn’s work there in 1950--he had a great painting in the show, but it didn’t win a prize. Diebenkorn was at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque at the time, and later that year when I went on a trip through the Southwest, I looked him up and bought three paintings, including the one from LACMA, for $300--which was all the money I had. I didn’t have control of a gallery then, and just bought the paintings because I was interested.”

That same year Kantor moved the Fraymart Gallery to a location on Beverly Boulevard where it operated under its original name for two years. In 1952, Kantor’s partner was dealt out of the game and the Fraymart became the Kantor Gallery. Five years later, in 1957, the gallery relocated to Camden Drive, where Kantor did business until 1966, when he closed shop and became a private dealer.

“Diebenkorn sold well, but I couldn’t sell the other stuff--maybe because the Diebenkorns were cheaper,” Kantor speculates. “His work was $350 a canvas, but a major Rothko or Motherwell was $500. I didn’t care that they didn’t sell though, because I was young and idealistic and showed the work because I believed in it.”

After 15 years, idealism began to wear thin for Kantor, who went on to a lucrative career as a private dealer specializing in French Impressionism.

“In 1966, I had a show of Georges Rouault’s prints and graphics. Everything was framed, and the most expensive picture was $300. One day (collector) Marcia Weisman came through the gallery and said, ‘Paul, I’ve seen these pictures--when are you gonna put up a new show?’ I told her, ‘Marcia, I’ll change the show when someone buys one.’

“Eight months later I still hadn’t sold a single picture! Around that time I got hepatitis and had to spend a month in bed, and one day I said to Ulrike, ‘I don’t wanna see that gallery anymore--close it and bring the paintings to the house.’ I didn’t want to be a shopkeeper in Beverly Hills anymore--but I’ve never wanted to stop dealing, because I like the whole idea of it. I love the subject and love having the work around. I just don’t like having to deal with people.”

Does he still love the work? “Yes,” says Kantor, laughing with surprise at the answer he finds himself giving. “I do.”

The next generation of Kantor galleries took root in 1959, when Ulrike Wegener came into the Beverly Hills gallery attempting to sell a Miro watercolor owned by her second husband.

“I gave her a low price, so she left and I never heard from her,” recalls Paul Kantor. “A year later I ran into her at a restaurant, and we married in 1960. She had no background in art when we met and didn’t want to be involved in my business,” adds Kantor, who had four children with Ulrike Kantor prior to their divorce in 1973. “In 1966, however, when I started working out of the house, she became more involved.”

“It’s true that when I met Paul I had no real background in art,” concurs Ulrike Kantor, who was born in Germany in 1934 and moved to Washington as an au pair in 1953. “Growing up in Germany I went to museums with my family and I’d always been interested in art, but that was the extent of my involvement. So, I learned a great deal from him.

“When I met Paul he was showing ‘young’ artists like Diebenkorn and Nathan Oliveira, and wasn’t making much money,” continues Ulrike Kantor, who settled in L.A. in 1955 when a modeling job brought her here. “One day he said, ‘I’m tired of being poor--I want to make money.’ I said the only way to do that is to go to Europe, buy a painting, bring it back here and sell it, and that’s what we did. The first thing we bought was a Picasso for $15,000, which was all the money we had. We sold it for $25,000 and felt very rich having made $10,000.

“We were good business partners, but our tastes diverge in significant ways,” she adds, “and I remember the exact moment when I decided I wanted to have my own gallery. It was one afternoon in the ‘60s when Paul and I saw a show of (Roy) Lichtenstein in a gallery on La Cienega. I told Paul, ‘I’d love to buy all these paintings,’ and he said, ‘We’ve been struggling for years to make money and you want to waste it on imitation Leger?’ I remember telling him then that one day I’d have my own gallery and show young artists.”

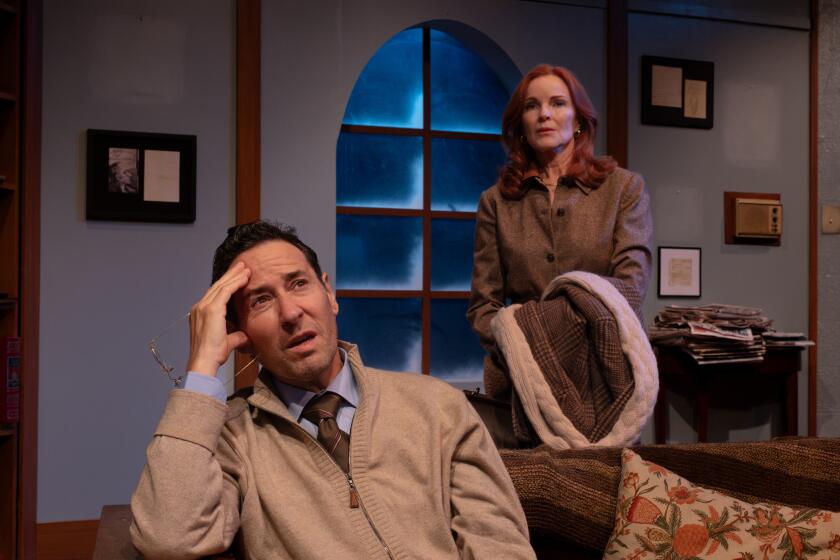

Which is what she did. After a short-lived first attempt running a gallery on Rodeo Drive in 1973, she opened a second gallery in 1979 where she showcased work by young L.A. painters such as Roger Herman, David Amico and Andy Wilf.

“I heard there was a new generation of artists developing downtown, so I went to see what they were doing and got turned on by a few of them,” she says of her decision to open the gallery, which operated on La Cienega until 1986.

“In 1983, one of my artists, Andy Wilf, and Paul Jr., the eldest of the four children I had with Paul, died of drug overdoses, and I started to lose interest in promoting artists,” she continues. “As the gallery was winding down I didn’t want to take on any new artists, but one month I was in a pinch for a show to put up and I wound up doing an exhibition of plein-air paintings. That was a relatively unexploited market in the mid-’80s, so I decided to deal them privately. I closed the gallery and began to deal out of my house, which is what I’m still doing.

“I’ll never have a gallery again--now that my son has one I don’t need to because we have similar taste. I think it’s great he’s carrying on the family business, and I’m especially pleased he’s showing young artists--if he’d just opened a shop where he was selling expensive things, it wouldn’t mean as much. Good artists tend to come in waves--I think we’re due for a great new crop, and I’m thrilled for Niels that he’s going to play a part in it.”

That he finds himself running a gallery at the age of 25 comes as no surprise to Niels Kantor. “As far back as I can remember I wanted to be an art dealer,” says Niels Kantor, who opened his gallery in November with an exhibition of paintings and ceramics by Jessika Wood (whose father, Roger Herman, showed with Ulrike Kantor). “After school, I always came home to galleries, so it’s an environment I really feel at home in.

“My father and I disagree on the subject of younger artists, and I want to be known for doing something of my own, but I also want to carry on the family name,” says Niels Kantor, who has scheduled a Diebenkorn exhibition for early next year.

“In December, I did an exhibition of work by Jean Dubuffet, and part of the reason I wanted to do it was because he’s one of my father’s favorites. My father spent 45 years doing this, and made an important contribution to this city in that he’s a reputable dealer and he chose to stay here. He showed that you can do it and live in L.A., which was a radical idea in the ‘50s when he started out.

“The biggest challenge I’m facing is finding good young artists,” says Niels Kantor, whose third show, an exhibition of work by Shane Guffogg and Henry Vincent, opens Feb. 4. “I ran ads in a few international magazines inviting artists to submit slides, and out of 350 people who responded I didn’t find one I could show. I went through the slides with my mom and dad--in fact, I consult them a lot when it comes to making aesthetic calls. I’d be a fool not to--it’s like having Einstein around to help you with your math problems.”*

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.