Drug Hailed as Breakthrough for Sickle Cell

WASHINGTON — Federal health officials Monday announced a major breakthrough in the treatment of sickle cell anemia, a disabling blood disorder, saying that clinical studies of the first drug therapy against the disease showed a dramatic reduction in episodes of painful and sometimes life-threatening “crises” in adult patients.

The findings were so compelling that the study was stopped early and a “clinical alert,” which indicates medical importance and public health urgency, has been issued to physicians nationwide, urging them to prescribe the drug, hydroxyurea.

Daily doses of hydroxyurea reduced the frequency of painful episodes and hospitalizations by about 50%, researchers said. Patients treated with the drug also required fewer blood transfusions.

It is the first therapy shown to prevent episodes associated with the disease, although it is not a cure. Until now such crises only could be treated with narcotic painkillers and intravenous fluids after they began.

“This is a significant advance,” said Dr. Claude Lenfant, director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, which released the results at a press conference. “Although it is not a cure, hydroxyurea therapy is the first effective treatment for this serious illness and may greatly improve the quality of life of sickle cell anemia patients.”

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited disease that is most common among people whose ancestors came from Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean basin and India. The World Health Organization has estimated that more than 250,000 babies are born annually worldwide with sickle cell, which causes chronic pain, organ damage and potentially deadly infections.

In the United States, it affects primarily blacks, about 72,000 of whom have the disease. One in 12 black Americans carries the genetic trait. Those with the disease have a life expectancy 25 to 30 years less than other blacks.

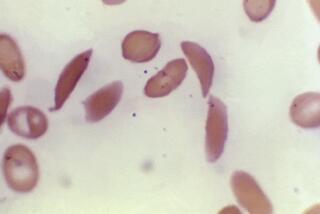

In patients who have the disease, molecules of hemoglobin stick to one another, forming long rods inside red blood cells, causing them to take on a sickle shape and become rigid. The cells are then unable to squeeze through tiny blood vessels, depriving tissue of an adequate blood supply, causing “crises.” These blood clots can be fatal, depending on where they occur.

The crises are regarded as the most disabling aspect of the illness. They often occur without warning, frequently requiring hospitalization and absences from work or school.

“It’s a bad disease,” said Dr. Samuel Charache, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, who was lead investigator in the study.

In the study, hydroxyurea therapy also reduced the frequency of acute chest syndrome--another symptom of the disease--a sometimes fatal condition characterized by chest pain, fever and an abnormal chest X-ray. Those on the drug experienced 50% fewer cases of acute chest syndrome than patients not on the drug.

“There was a remarkable number of patients (in the study) who came in and told their doctors: ‘I just don’t feel I’m sick anymore,’ ” said Dr. Michael L. Terrin, another investigator, of the Maryland Medical Research Institute.

Ralph Sutton, deputy director of the Los Angeles-based National Assn. for Sickle Cell Disease of America, said: “We’re very excited about the news. It potentially points to a very radical improvement in the quality of life for a lot of people who suffer from sickle cell disease.”

The drug is manufactured by Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. of New York. It already has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of another blood disorder, polycythemia vera, a condition in which too many red blood cells are produced.

Lenfant said that the institute has notified the FDA of the new results and the agency is expected to approve the new use for the drug after it reviews the study data. However, since the drug has been licensed, physicians are free to prescribe it for sickle cell treatment immediately, Lenfant said.

Doctors frequently prescribe drugs for so-called “off-label” uses, which is not a violation of law. Insurance companies and other third-party payers, however, sometimes deny or resist covering such uses, although the FDA has called non-payments inappropriate.

Researchers emphasized that the drug should not be prescribed for children since it has not yet been studied in them. Researchers plan to begin the first studies in children soon, they said.

There are side effects associated with the drug, including mild, reversible bone marrow suppression that can lead to cytopenia, a serious decrease in blood counts.

Researchers said that patients taking the drug for polycythemia vera have experienced a higher rate of leukemia, although that has not been seen thus far in sickle cell patients taking the drug.

But, because the drug’s long-term effects are unknown, patients should return frequently for checkups, researchers said.

Between January, 1992, and April, 1993, the study enrolled 299 adult sickle cell anemia patients age 18 and older at 21 centers across the country. All had suffered at least three painful crises in the previous year.

The trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, meaning that neither the patients nor the physicians knew who was getting the drug and who was receiving a medically worthless placebo, given for comparison purposes. Half of the patients received the drug while the other half were given the placebo.

The trial was slated to last until May, but an independent scientific panel monitoring the study thought the results so significant that its members recommended the trial be halted and that patients on the placebo be offered the drug.

“The results were strongly positive . . ,” said Dr. Cage Johnson, chairman of the panel and director of the comprehensive sickle cell center at Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center. “The drug was effective.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.