Over There : The American occupation of the British Isles in the early 1940s : RICH RELATIONS: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942-1945, <i> By David Reynolds (Random House: $30; 592 pp.)</i>

- Share via

A crude but typical English joke traded during the American soldiers’ occupation of the British Isles in the early 1940s described a new brand of ladies’ underwear: “One Yank and they’re off.” The Americans, it had seemed, were preoccupied with making love, not war. However, I was far too young for such matters. I bring more romantic memories to this marvelous monolith of a book.

Still clear in the cinema of my mind is the clean-cut, square-jawed GI sheathed in a smooth, silky uniform, lifting me from that sooty railway compartment, calling my mother “ma-ma,” inquiring after her “folks” and distributing “candy.” After discharging these diplomatic duties he casually leaps into a waiting “jeep” where his “buddy,” with one movement of a high-booted leg, throws the gleaming machine into gear and roars past the line of battered taxis and muttering Tommies, into a typical London fog.

Now, thanks to English academic David Reynolds’ epic study--fact-packed, anecdote-filled, and with maps, tables and even a chart listing “Extramaritally Conceived Maternities per 1,000 Unmarried Women in England and Wales”--I learn that my hero was but one of more than 3 million American servicemen: “regimented tourists” who visited our cramped little isles during World War II. Sharing a “single language and a double culture,” the Yanks were to train, wait, wench, drink, be bored or make love (and sometimes babies), before once more making Europe free for democracy and, naturally, for its accompanying culture and comforts: Coca-Cola, Hollywood, MTV and McDonald’s.

As Reynolds points out, and Churchill knew when he wooed F.D.R. for his distant cousin’s material might, Germany’s defeat in the West was to be an American victory, due to superior firepower, masses of manpower and lots of that special Yankee know-how and get-go.

But D-day was only possible because of another campaign waged within a friendly nation, an ally: the so-called “invasion” and “occupation” of Britain. The blitz-dazed but brave islanders were to host the building of the world’s largest military base, what chauvinist George Orwell derisively dubbed, “American’s Airstrip One.”

Military help, both metal and flesh, was one thing, but increased Americanization was another. For decades, the paternalist British cultural elite had been railing against Hollywood products, too popular with women, children and the working classes. American movies, with their horrid slang and their freewheeling life-styles, were seen as a threat to traditional English values. “Unsophisticated” local audiences needed to have their tastes “corrected,” thundered the Times (of London) in 1935.

And now, here in 1942, come these vulgar gangsters and cowboys (the British press claimed that Eisenhower had been a Texas steer-roper), stepping seemingly straight off the screen to desecrate England’s green and pleasant land. In turn, the visiting servicemen knew little of their Anglo-Saxon relations beyond movie stereotypes of Kipling-esque empire builders and Dickensian eccentrics (see Gary Cooper in “Lives of a Bengal Lancer” and W. C. Fields in “David Copperfield”). There was, too, the puzzle of how a country could be called “Great” Britain when you could traverse it by propeller plane in a couple of hours. Therefore, much tact and indoctrination was needed to win the hearts and minds of both the impoverished hosts and the rich but friendly invaders.

Eisenhower, soon to be Supreme Allied Commander, emerges as the hero of “Rich Relations.” While Patton sneered that he’d sooner take orders from an Arab than from a Limey, Ike went along willingly with his President’s orders to be nice to the locals, even to the extent of taking an English lady friend. As he told his London staff upon arrival: “Gentlemen, we have one chance and one chance only of winning this war and that is in complete and unqualified partnership with the British.”

As soon as military matters had been dealt with (finding battle training space even though you had to lob shells over the rows of houses, building airstrips on quagmires, getting used to driving down narrow lanes on the wrong side of the road) attention could be paid to the more pressing social matters.

The War Department fed the GIs famously, with an emphasis on beef. This at a time when the British were rationed to a measly four ounces of meat per week. The reasoning behind the American strategy was that since the average GI had little motivation to fight (as opposed to the British and Russians who were defending hearth and home) they should be encouraged to stick together as an army by being showered with every home comfort. Neither F.D.R. nor Gen. George Catlett Marshall were happy with such pampering, but they had to answer to Congress, eagle-eyed by the mighty mothers of America who would tolerate nothing but the best for their boys.

As well as good food (shipped in through Nazi-infested waters by the British merchant fleet) the GIs were fed movies, stage shows (which some called “live movies”) and Glenn Miller. When tired of the cocoon of base life, the servicemen could sally out to their exclusive service clubs, a sort of super hotel chain run by the American Red Cross. “Rainbow Corner,” one of the most popular clubs and a prize for any Limey serviceman lucky enough to be an invited guest, was conveniently situated near Piccadilly Circus with its standing army of prostitutes and amateur “good time gals.” The “Piccadilly Commandos” (and their sylvan sisters the “Hyde Park Rangers”) gave Yanks better service (a bed rather than an alley wall) because GI pay was three times more than the Tommies got.

No wonder the British soldiers took up the one-liner about the Yanks being “oversexed, overpaid, overfed and over here.” But until Reynolds’ book I’d never known the GI riposte that the Limeys were “undersexed, underpaid, underfed and under Eisenhower.” Such volatile opinions were confined to the military (and certain of the British upper classes). For the most part the local population, especially young women and children, took to the exotic Yanks like modern Muscovites to a cheeseburger.

Even so, in order to avoid giving offense to the natives, the U.S. top brass commissioned an etiquette program, explaining that these two English-speaking allies were equal but different. For example, Eric Knight, English-born author of “Lassie,” provided useful pointers in “A Short Guide to Britain,” a pamphlet issued to arriving GIs: no bragging, no arguments about religion or politics, and absolutely no criticism of the king or queen. An instructional film showed Burgess Meredith committing such sins as chatting up a barmaid, throwing his money around and making fun of a Scotsman’s kilt. When Meredith was pictured alighting from a train with a black GI, a commentary explained that although such behavior might not be acceptable back home, it was quite OK in England. Margaret Mead, the anthropologist famous for her studies of South Pacific native life, contributed a pamphlet in which she asked GIs to respect and not judge the British love of history and their elders.

But most GIs, like their British brothers-in-arms, weren’t bothered by the advice of authorities. Instead, those who so desired made themselves at home with the locals in the age-old folksy American way. They played darts and politely drank the weak, warm beer; they sometimes sauntered into homes for tea and sympathy, particularly if there was a daughter around. Ike encouraged his boys to be “Handy-Andy” around the house and to always carry a “full day’s ration of meat, fats and sweets.”

However, when fraternization turn to fornication, the authorities in both armies grew uncomfortable. As Reynolds plainly states: “The root of all evil during the American occupation was ‘sex.’ ” From the very start, complaints had been lodged about GIs accosting British wives in front of their husbands, of paying “social calls” when they knew hubby was out.

The commanders realized that their troops were bored, waiting so long for the invasion of Europe, and that sexual relations with the natives, although undesirable, could at least be made safe and comfortable. Even so there was a venereal disease epidemic in 1943 that only abated the next year as the lads grew excited at the prospect of battle. War seems to often act as a sex-drive substitute.

African-American libido on the loose in merry olde England was the biggest fear in the sexual situation. Both armies were guilty of a racist policy, a de facto segregation. The War Department view continued to be that “Negro” soldiers could be a liability and thus should be used mainly in the theater of “supplies.” But by 1944, manpower as battle fodder was in short supply and by the eve of D-Day there were 130,000 black soldiers stationed in a land where minorities were minuscule.

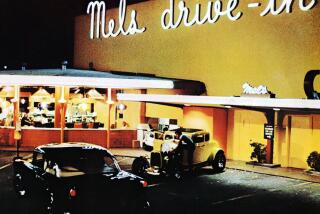

About 70,000 British war brides did make it to America (despite official disapproval) where, generally, they settled down and were soon Americanized. Some felt they’d been fooled by the glamorous image: Reynolds shows us how one well-bred girl, told that her father-in-law owned a chain of smart restaurants, discovered they were in fact peanut stands outside baseball stadiums--and she was to serve in one.

And there were war babies left behind, fatherless. Reynolds tells the touching story of Shirley, daughter of a vanished GI. After years of searching she finally located her father in 1987, in Sacramento. He could remember nothing about her mother, but he fully accepted Shirley as his daughter. The horrors of Normandy had killed off certain memories.

It is sad to see that the attitude of the British elite toward America hasn’t changed. A cursory glance at British “quality” newspapers and magazines reveals the same old jealousy and resentment, particularly of American mass culture--to her movies, her fast food, to the whole gorgeous dream of California.

And yet, as I find to my slight inconvenience, the flights to Los Angeles are always pretty full, with Britishers eager to sample the home delights of their “Rich Relations.” Enough said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.