Spouse to Be Charged in Wife’s 1987 Slaying : Canyon Country: A woman Guy Dean Bouck raped ruined alibi that had removed him from scene of the fatal shooting.

From the beginning, police suspected that Guy Dean Bouck had killed his wife, Stephanie, for the insurance money. But they couldn’t prove it.

After her body was discovered on Jan. 3, 1987, he was arrested but quickly released for lack of evidence. There were no murder weapon, no witnesses, no reason why his fingerprints shouldn’t be all over the house they shared in Canyon Country. The burglar alarm was set, but silent, when the body was discovered by the victim’s daughter.

But Thursday, more than eight years after the fatal shooting of Stephanie Bouck, an accountant everyone knew as “Stevie,” Bouck will formally be charged in San Fernando Superior Court with her murder.

Bouck, a former Army paratrooper who fought in Vietnam, made two crucial mistakes that led up to his indictment on a murder charge, sources and court records say:

He waged a bitter family court battle over his wife’s estate, which aired his dirty linen and produced a rare result: A civil court judge ruled in 1990 that Bouck most likely had killed his wife--and therefore should inherit nothing from her.

And, on Jan. 15, 1990, in a Northridge tire store several weeks before the probate battle began, Bouck raped the woman who had provided his alibi for the night of the murder. The woman later would be a powerful witness against him--at the rape trial, in the probate case, and finally--sources close to the case say--before a Los Angeles grand jury.

The grand jury has indicted Bouck, 47, on a count of murder with three special circumstances that could carry the death penalty: lying in wait, torture and killing for financial gain, according to court records.

“Avarice and greed, coupled with a sociopathic attitude, usually leads you astray,” prosecutor Jeff Jonas said. “Fortunately, there’s no statute of limitations on murder.”

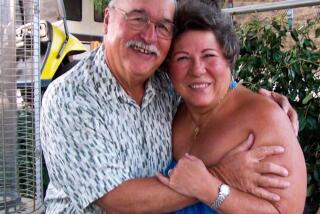

“It’s about time. It’s been a long time in coming,” said Debi Carll, who discovered her mother’s body in the master bedroom of the Bouck’s Canyon Country home and later led the probate fight against Bouck.

“He killed her for her life insurance money, and there’s no way he was going to get it,” added Carll, now 35. “There was never a question in anyone’s mind.”

Because the case still is shrouded in grand jury secrecy, few specifics are known, and Jonas, who began working on the case in October, 1993, declined to discuss details. The transcript of the testimony the grand jury heard remains sealed.

But much of the story has been laid bare in other court files--including the rape case that drew a 13-year prison sentence for Bouck, and the six-volume probate case.

Bouck stood to inherit 80% of his wife’s $100,000 life-insurance policy; half their house on Emmett Road, her 1987 Nissan 200 SX, and a money market account, the documents show.

The records also reveal Bouck’s long record of involvement in violence toward women and children.

In a February, 1990, court brief, attorney Beth E. Yoffie, on behalf of Carll and the estate, detailed Bouck’s history of domestic violence, dating back to September, 1971, when his stepson, Michael Gennard Kelley, age 4, died at Fitzsimmons Army Hospital in Colorado Springs, Colo., of a fractured skull and head trauma.

The child was convulsing and comatose, his body covered with bruises, when he was brought to the hospital.

*

A grand jury investigated Bouck, who was in the Army, and his then-wife, Cheryl, but no charges were filed: “The district attorney’s office felt (Bouck) should be handled through military authorities to receive mental help for his problem,” Yoffie said.

Five years later, according to court files, Bouck pleaded guilty to felony child abuse in Los Angeles Superior Court in Norwalk for injuries suffered by another child, Jennafer Parsons, described as “a victim of abuse and multiple bruises over a period of time.”

Jennafer was a healthy 2 1/2-year-old until Bouck moved in with her mother, Joan Parsons, in July, 1976, the brief states. By the end of August, Jennafer had received medical treatment about nine times and had been hospitalized twice. X-rays revealed two distinct spiral fractures of her leg that occurred at separate times.

On Aug. 25, 1976, Jennafer “was found (lying) stiff and pale, her left leg twisted, with bumps on her head. Paramedics took her to the hospital,” the court papers state. Her head was swollen on both sides.

She had two black eyes, head injuries with profuse scalp bleeding, bruises on her left leg and was walking on the outside of her foot.

Bouck initially told police Jennafer had fallen off a swing, but later admitted he had struck her when she rejected his attentions, according to Yoffie’s brief.

Bouck said she had fallen backward and may have hit her head on the stereo system. But he later admitted striking her, the brief relates. He explained he may have “hit the same places or same bruises repeated times or time after time,” saying he used karate techniques learned in the military, the brief said.

He was allowed to change his plea to not guilty and the criminal case was dismissed after he completed probation, court records show.

Ten years later, Bouck allegedly turned to violence again when his latest marriage, to Stevie, began to dissolve, Yoffie states in court papers.

“In December, 1986, Guy Bouck realized his wife really intended to go through with the divorce. The easy life he’d grown accustomed to was about to come to an abrupt halt,” she said in court papers.

“But Bouck had a plan--and only a few days to carry it out. On Jan. 2, 1987, he brutally murdered his wife . . . “ Yoffie alleged in the court papers. Then, he filed a claim for her estate, which included her half of the house and $80,000 in life insurance policy proceeds.

“Bouck thought obtaining his wife’s wealth in court would be as simple as murdering her,” Yoffie alleged in her brief.

The last time her family saw Stevie Bouck alive--New Year’s Day, 1987--she was leaving a Denny’s restaurant with Bouck.

Two days later, Carll found her mother’s body sprawled on her bed, her legs hanging over the sides. She was wearing a nightgown and socks. She’d been shot four times--twice in the chest, and in the head and neck. Three of the wounds could have been fatal by themselves.

Her hands and wrists were bruised, indicating she’d been restrained.

Carll was appointed executor of the estate on March 20, 1987, and immediately sought to exclude Bouck as a rightful heir.

In June, 1989, he filed a motion asking a judge to decide in his favor. He claimed he did not kill his wife, and had no idea who did.

Judge Martha Goldin denied his petition on July 29, 1989, and Bouck appealed to the state Court of Appeal and Supreme Court without success.

In fighting the action over her mother’s estate, Carll asked a probate court for a fact-finding hearing into her death. In April, 1990, probate Judge Richard C. Hubbell issued the unusual order finding that a preponderance of the evidence showed Bouck had “feloniously and intentionally” killed his wife.

*

The ruling followed a two-month hearing that was, according to Yoffie, “the civil equivalent of a murder trial.” During the trial, investigators identified Bouck as their prime suspect. His former alibi witness changed her story, saying he was not with her the entire night his wife was killed.

Six months later, she explained why as she stood before a San Fernando judge and asked him to send Bouck to prison for raping her:

“The faces of the victims vary, however the actions and the words and the attitudes of the perpetrator are the same. Michael Kelley and Stephanie Bouck are dead. Jennafer Parsons, Cheryl Kelley, Debi . . . and I are alive. All have experienced the wrath of Guy Bouck and all of us live in terror that one day he will finish the job.”

Bouck since then has been serving his 13-year sentence at a state prison in Corcoran, as Los Angeles County prosecutors took a renewed interest in the death of his wife, leading to the grand jury indictment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.