Next Step : Haiti Looking to Jump-Start Its Comatose Justice System : Not a single trial has been held since Sept. 19, 1994. ‘If there is no rule of law, there is no civilization,’ warns an American judge sent to help out.

Justice in Haiti isn’t blind. It’s dead, and the rotting corpse is threatening to undo the promise brought here by U.S. troops when they drove out the country’s bloody military regime and restored democracy.

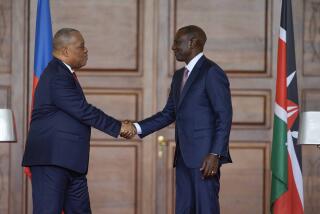

That assessment, shared by nearly everyone involved in trying to put Haiti together again in the wake of the Haitian military’s three years of corrupt and cruel rule, was summed up in one word by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

“Absolutely,” he answered when asked if the lack of a working system of justice threatened to wreck his efforts to establish a stable, safe and prosperous government.

To U.S. Maj. Gen. Donald Campbell, the New Jersey judge who was called back into military service to help restore Haiti’s judicial system, “everything hinges” on the success of his program.

“If there is no rule of law,” Campbell said last week, “there is no civilization.”

Right now there is no law, and even the well-intended international efforts to put things right are caught up in controversies over the assumptions behind Campbell’s plan as well as measures to implement it. A power struggle between key U.S. government agencies working to restore democracy to Haiti has not helped either.

To understand the depth of the problems, consider some statistics.

By very conservative estimates, guesses really, at least two people are murdered every day in Port-au-Prince alone. Since there is no effective police force or working court system, there are no data available on crime rates for robberies, assaults or other transgressions.

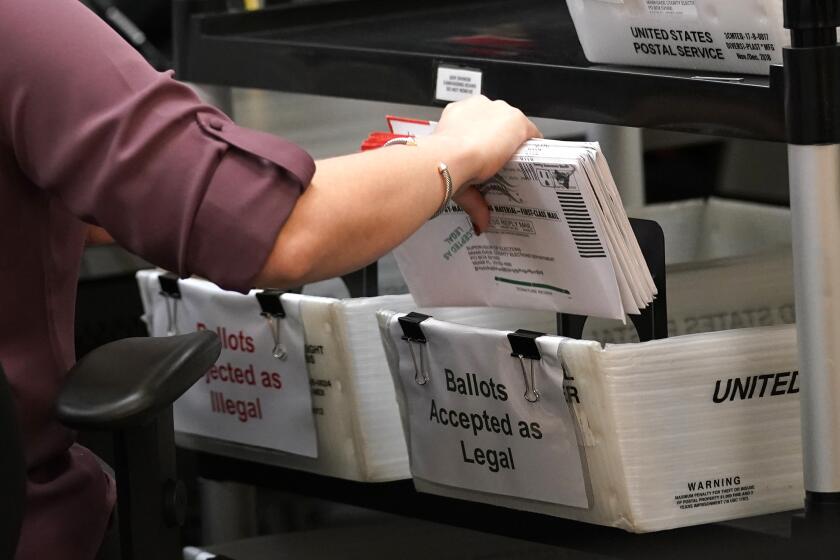

What is known, however, is that not a single trial has been held in Haiti since last Sept. 19, the day that U.S. troops arrived here to restore Aristide to the office he was driven from three years earlier by the Haitian military.

A 3,000-member interim police force cobbled together from the now-disbanded army has a total of 32 weapons, all small-caliber pistols. But since many Haitians and foreign experts believe that the interim force is made up mostly of thugs, their lack of arms is not necessarily a negative.

What is a negative is the state of the judicial system. Only 5% of the nation’s 200 judges have complete copies of Haiti’s basic legal code and reference books. Even if the judges had the books, legal professionalism would be lacking. Only 6% of Haiti’s judges are law school graduates, and just 8% are licensed attorneys. Nearly 66% lack legal training of any sort.

The judges were paid the equivalent of just $30 a month until recently, when their pay was increased to between $100 and $150.

“Their pay was tripled,” Campbell said, “but that’s not enough, less than a policeman. It’s an open invitation to corruption.”

Working conditions in the courthouses are deplorable.

To Campbell, 51, a highly respected career jurist who directed civil affairs programs for the U.S. Army in Iraqi territory after the 1991 Persian Gulf War, all of this can be fixed, and without changing the basic Haitian legal system.

“We absolutely will not attempt to replace that system,” he said of the 20 U.S. lawyers and security experts who are implementing the $24-million, U.S.-financed program aimed at repairing the Haitian judiciary. “I wouldn’t offer one opinion on the substance of the law. I’m trying to improve conditions” by training current judges and giving them adequate materials and courthouses.

“If you took the laws on the books and enforced them,” Campbell said, “you would be 95% home.”

As a result, the focus of the U.S. aid effort is a one-week refresher course for judges and the provision of materials ranging from erasers to desks to ledgers for registering births, deaths and other statistics.

While Campbell’s approach is favored by Haitian lawyers and officials, it is seen as a disaster by leaders of popular movements and even some U.S. diplomats.

Jean Cevanne Baptiste, head of the National Peasant Movement, said in an interview that “the judicial system is rotten to the core. Giving training to existing judges is giving training to criminals. They should revoke all those judges and appoint all new ones.”

Jean-Joseph Exume, who was recently appointed the Haitian minister of justice and was called “a visionary” by a senior U.S. official here, also questioned Campbell’s assessment of needs.

Saying that “justice can be bought by the highest bidder,” Exume has circulated one of his speeches charging that “the Haitian judicial system is not working. . . . It no longer responds to the needs of Haitian citizens.

“The codes are inappropriate and obsolete. . . . Corruption has become institutionalized. . . . The Haitian judicial system lacks everything . . . human and material resources, independence and honesty,” Exume said.

Some U.S. officials who disagree with the current program have proposed far more drastic reforms, including replacing the existing Haitian system, which is based on the French Napoleonic Code, with one resembling the U.S. system.

The dispute that followed this disagreement led to a three-month delay in implementing any reforms, one U.S. official said, and forced State Department legal officials and experts in Haitian affairs to make a two-day emergency trip here last month to settle things.

For the moment, and probably the long run, Campbell’s program is favored by the United States and Aristide, who signaled what he wanted when he fired a previous justice minister for opposing the U.S. plan.

“For better or worse,” said a U.N. official here, “Haiti’s need for real justice will be met by what you Americans call applying Band-Aids and not radical surgery.

“All we can do is hope for the best.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.