Year After Suffers

I can’t forget; forgetting doesn’t exist. --Rwandan Evariste Twahirwa, 26

Obsession leads Rwanda to many miseries.

In abandoned churches, blood still hangs in hardened globs from the brick walls. Windows of government buildings remain spider-webbed from bullets.

In back yards and empty fields all across Rwanda, red dirt still rises high and bare over graves.

One year ago this day, the genocide of Rwanda commenced.

Today, this small Central African nation is still consumed. It is pained, hollow, angry, broke and, to be frank, a long way yet from hope.

*

I was home with my sister. At 3 a.m. gunfire woke us. We listened to the radio. It was classical music. Then it was interrupted to say that the plane went down. We were told that everyone should stay home. My God, my thought was: They’re going to start killing everyone, especially Tutsi.

*

And so they did. Using machetes, clubs, the toes of boots and worn rifles, Rwanda turned on itself.

An airplane carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana had exploded over Kigali’s airport the night before, April 6--most likely shot from the sky by those bent on slaughter, a grotesque “final solution” to Rwanda’s ethnic rivalries.

Up to a million men, women and children would be killed. Four million people, half the country’s population, would flee their homes. Tens of thousands of women would be raped. And 80,000 children would be orphaned or abandoned.

And in the year since?

Today the streets of this town are again alive with people. Many are new immigrants. Old residents died or fled. Or at the least they were unimaginably scarred.

Rwanda is a different country now, a country obsessed. Where is justice? Where is a helping hand?

*

At 2 p.m. exactly, the presidential guards came. They screamed to open the door. Then they broke it open. They went room by room. They said, don’t be scared, they only wanted money. I went in the bedroom and climbed into the attic. They threatened to rape my sister. . . . I broke the tiles in the roof and ran. They killed her.

*

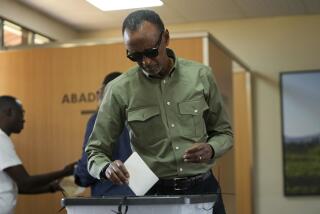

At Evariste Twahirwa’s Kigali bungalow, 13 bullet holes can be counted in the wall of the living room where his sister was shot. In the back yard, a pile of bright red dirt is her grave. He lifts a large rock. This is the one the killers used to bash in the front door.

About 32,000 accused murderers have been imprisoned since the massacres, a number that increases by 300 or so each day. The jails are so overcrowded that 22 died in a single cell recently of what was reported to be suffocation. The government Thursday struggled to begin the first trials of six accused killers.

In a shabby courthouse shot up in the war, eight bedraggled men in pink prison jumpers, six of them accused of genocide, were led from the back of a Toyota pickup and marched before cameras and three judges for the start of their trials.

But the truth is, Rwanda has almost no institutions to administer justice. According to Lee Woodyear, in charge of international human rights monitoring here, 80% of the judges and judicial staff are dead, have fled the country or are in jail. There are few defense lawyers, hardly any desks or paper or photocopiers.

Even if one could imagine processing 50 cases a week, it would take a dozen years to try those now in custody. And the government says thousands more are guilty of murder.

*

A much-ballyhooed investigation by the International Tribunal of the Hague will not announce its first indictments for perhaps four more months.

Meanwhile, the world heaps food and sympathy on the 2 million Rwandan refugees now huddled in neighboring countries, many of them Hutus accused of genocide against the minority Tutsis. Strengthened by relief help and perhaps being rearmed, these vanquished fighters are increasingly mounting guerrilla incursions into their homeland.

Here in Rwanda, the army remains the only force for stability. But its soldiers have received only two months’ pay in the last nine months. Their movements are watched by 5,500 U.N. troops and human rights monitors.

Hard-liners in the government are growing impatient and have begun to lash out ominously at the developed world for what they call misguided priorities.

“You can see the vicious circle,” U.N. Special Representative H.E. Shaharyar Khan said. “Like all vicious circles you don’t know where it starts. But every point seems to increase the tension to the next point.”

The world, in simplified terms, would like to see reconciliation between the Hutus of the former government and the Tutsis of today’s. The Tutsi survivors want justice.

*

My mother and father were killed. We were 10 children. Eight were killed. What kind of reconciliation can you have with people who kill your family?

*

Now, one year later, Twahirwa revisits the church at Nyamata, 30 miles south of Kigali, where his mother, father, fiance and siblings were herded along with 800 or so other Tutsis. Hutu militia then opened fire through the breezeway and into the tin roofing. They tossed in grenades. Those who tried to flee were hacked to death with machetes.

The blood-splattered church is no longer used for worship. The dead are buried in a mass grave in the yard behind, marked with a single cross. An orphanage has been established next door.

*

Day by day, month by month, it has become harder. It’s like a weight on my chest. . . . I used to come home here on weekends. Now on Sundays I ask, where do I go?

*

The slaughter in Rwanda was systematic and well-planned. It was orchestrated by extremist Hutu leaders, conducted principally by local youth militia and fueled by frenzied kill-or-be-killed broadcasts on government radio.

“The killing was an attempt to unite the Hutu behind an extremist platform dedicated to the eradication of the Tutsi and all moderate political opposition,” the human rights organization African Rights said.

The plan failed. A Tutsi-led army advanced from the north through the spring and summer of last year and drove the Hutu extremists, their families and followers to the south. Today, 1.2 million live in Zaire, 200,000 in Burundi, 700,000 in Tanzania. And 300,000 live in U.N. camps inside Rwanda.

*

A year ago, the world let Rwanda down. The United Nations had troops here last April, and Western diplomats knew the Hutu extremists were stockpiling weapons and training killers. But the United Nations had no mandate to quell the slaughter, or so it said.

Instead, when the president’s plane and Rwanda itself exploded a year ago, the United Nations pulled out most of its troops and garrisoned the remainder.

Now the United Nations is back in force. But again, the question arises: Does it have the proper mandate?

The United Nations is here to secure peace. But Rwanda’s new leaders argue that it is time for the world to offer redevelopment assistance. This January, other nations agreed and pledged $611 million. So far, only a trickle has arrived, and roadblocks to long-term support seem to be arising every day.

In its frustration, the Rwandan government has begun broadcasting strong criticism of the United Nations. Soldiers are accused of rape and encouraging prostitution.

Withering criticism, and occasional harassment, is directed at relief agencies. Nearly 180 private, foreign-based relief and charity groups are here, many of them raising money by reminding the world of Rwanda’s horror.

But the government says too much of the money is being spent on fancy cars and two-way radios and projects of dubious priority.

*

I was in hiding for months. I ate fruit from trees and grass and gathered rainwater and drank from gutters. There was always shooting. . . . There were bodies everywhere. I was like a crazy person.

*

Hutu versus Tutsi. That is the way Rwanda’s troubles are characterized. But it is really not so simple. Today’s government, though established by a Tutsi-led rebellion, is a mix of the two ethnic groups. And some of the bravest stories being told on this one-year anniversary are of the Hutu moderates who risked their own lives to shelter Tutsi friends.

Twahirwa was protected and fed by such a woman. His sister was given a proper burial by the Hutu neighbor. The woman’s children prayed that the dreaded militia would not burst in and kill him.

Today, Twahirwa cannot find her. Perhaps she is a refugee in those squalid camps. How can he help her? He cannot enter those camps to look for her, because in those camps may be the men who killed his family. And they would be happy to finish him.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.