COLUMN ONE : Fertile Ground for Poetry : Led by Pulitzer winner Philip Levine, Central Valley writers turn out verse as stark as the farmland around them. The inspiration? ‘You have to do something to say, “Here I am,” ’ one explains.

The second-loneliest job in the Central Valley is toiling over the land, 15 million fertile acres alternately seared by sun and shrouded in fog, ringed with mountains and crisscrossed by irrigation canals.

The loneliest job is turning heat, dust and poverty into poetry. Sherley Anne Williams has done both, tilling fields and cultivating verse:

Land flat as hoecake

Summers hot enough

to fry one Crops fanned

out in fields far as

eyes can see

every

Time we work a row

another appears

on the horizon

A generation’s worth of poetry--spare, powerful and nationally celebrated--may be the most surprising harvest from the agricultural belly of California. It springs from the sons and daughters of the valley, largely working-class bards like Williams whose verse has been shaped by a landscape that many find hard to love.

“It’s ugly countryside. Through ugliness you can make a tremendous literature,” said Gary Soto, among the most published and praised of the Fresno poets.

There is no “Fresno school of poetry,” no particular style that connects the big careers and little books of the award-winning writers of the San Joaquin. There are, however, common themes.

Luis Omar Salinas, who lives in nearby Sanger and has read his work at the Library of Congress, hears “a certain inner voice of the valley--loneliness, enthusiasm.” Jean Janzen, author of three collections since taking up poetry at 46, finds the poetry as direct and honest as the region: “You can’t escape the brutal sun,” she said. “It’s flat land. It shows what you are. There’s no place to hide.”

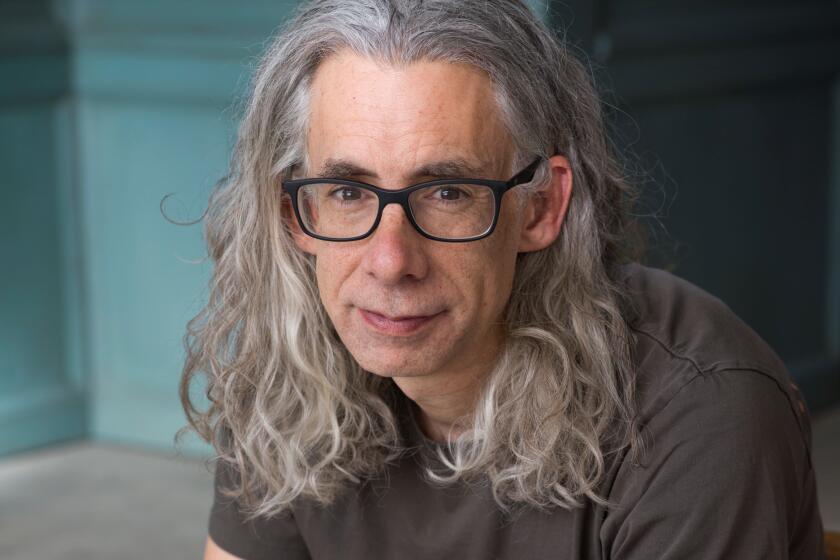

Then there is the teacher, Philip Levine, who in April won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, drawing attention to the colony of writers he founded at Cal State Fresno (then Fresno State College) in 1958. Such an honor, he told his hometown newspaper, “just proves you can be in our dear little crummy village, which I dearly love, and produce something for a national audience.”

The locals, however, are a harder sell. News of Levine’s Pulitzer got a little story on the bottom of the Fresno Bee’s front page and two poem fragments reproduced inside. When basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian hired on at Cal State Fresno just two weeks earlier, a banner headline proclaimed, “It’s TARK TIME,” and a dozen stories peppered the paper.

Tarkanian T-shirts are for sale all over town, “while as of press time there are no ‘Phil the Thrill’ T-shirts in any mall,” Bee columnist Jim Wasserman wrote in a commentary bemoaning Levine’s anonymity.

Still, Levine’s volumes--which have won nearly every major writing award--fill the shelves at Fresno’s new Barnes & Noble bookstore, where they rub covers with the likes of William Saroyan, Fresno’s other Pulitzer Prize-winning son.

And dozens of Levine’s former students make up an enduring community of poets and writers who chronicle life in the Central Valley and write and teach at major universities nationwide.

Soto, who grew up doing farm work around Fresno, writes poetry, essays and children’s fiction from Berkeley. Williams, the daughter of migrant workers who settled in Fresno when her father contracted tuberculosis, writes and teaches at UC San Diego.

But wherever these poets have landed, says writer Gerald Haslam in a book of essays called “The Other California,” they have created a literature that is uniquely Californian, “one that is passionate and deeply concerned with the fecund but indifferent earth that makes valley life possible.”

Plum, almond, cherry have come and gone,

the wisteria has vanished in

the dawn, the blackened roses rusting

along the barbed-wire fence explain

how April passed so quickly into

this hard wind that waited in the west.

--from “Llanto” (for Ernesto Trejo), by Philip Levine

When Levine came to this hard valley in 1958 as a young professor, Fresno was but a third of its current size and had just barely claimed the title of America’s No. 1 farm county. The Detroit native was fresh from a year’s fellowship at Stanford. He came to Fresno State because there was a job.

What he found was a school he describes in a series of autobiographical essays as a “second-rate California college” and a dean with a face “unfurrowed by thought” who tried to sell the city boy on the lure of the rural.

“It was unexcelled for hiking, which was his favorite sport,” Levine wrote in “The Bread of Time.” “Horse racing was my favorite sport, but I made no mention of it, nor did I mention that hiking was what we did in Detroit when the car broke down.”

For four long and lonely years, Levine mailed his poems to friends around the country, starved as he was for a critical eye. Then, another job for a writing professor opened up and he persuaded poet Peter Everwine to join him in Fresno, a city that felt like the end of the Earth but was actually the geographic center of California.

“Once Peter came,” Levine, 67, said in an interview, “then I felt I had something, a community of two, a poet who was an equal.”

Fresno was--and still is--a working town, the perfect place for a blue-collar poet like Levine, whose early resume was strictly heavy labor: wheeling racks of sliced soap chips at a soap factory, working hot metal at Chevrolet Gear and Axle.

The New York Times Book Review has called him “our preeminent poet of working life” for his portraits of the men and women who shoulder the burdens of the industrialized world. Many of the Fresno poets since have shone similar light on rural labor and the chancy nature of an agricultural life.

Poverty is obvious in the Central Valley. It is easy to be poor here--many are--and quiet enough to think. Nature is generous; society is not. While the writers here don’t glamorize the pain, in such tension they find material--and plenty of it.

When autumn rains flatten sycamore leaves,

The tiny volcanos of dirt

Ants raised around their holes,

I should be out of work.

My silverware and stack of plates will go unused

Like the old, my two good slacks

Will smother under a growth of lint

And smell of the old dust

That rises

When the closet door opens or closes.

The skin of my belly will tighten like a belt

And there will be no reason for pockets.

--”Rain,” by Gary Soto

Writing poetry here means “trying to cope with the huge and brutal facts of the landscape and of the social structure which is so frozen,” Levine says. “The same people are gonna be poor and gonna do the hard work.”

The children of the Central Valley, unlike Levine’s later students at high-toned schools such as Brown, Tufts and Vanderbilt, have always understood this poet’s major lesson--that, until you fail as a writer, you cannot succeed.

“My students at Fresno State didn’t have any trouble with that,” says Levine, who retired from Cal State Fresno in 1992, after more than a decade of dividing the year between California and East Coast schools. “They’ve already failed. They’re here. But it’s out of the second-rate schools that the best poets come.”

Cal State Fresno has rarely had the luxury of wooing talented young writers from around the country. Instead, says poet C. G. Hanzlicek, director of the creative writing program, “we find people already here.”

Through the years the longtime core of the writing community has found and helped form scores of poets, women and men of “diverse and unlikely backgrounds,” Levine says, with “lives to write about that hadn’t entered poetry.”

Writers such as Lawson Fusao Inada, who has published two collections of poetry and whose work is inscribed in stone alongside Oregon’s Willamette River. Inada’s mother was born in the back of the Fresno Fish Market, which his family founded in 1912. His latest book, “Legends From Camp,” is in part a poetic memoir of childhood years spent interned behind barbed wire during World War II.

Larry Levis, who has published five collections of poetry and won National Endowment for the Arts and Guggenheim Foundation fellowships, grew up on a ranch in post-war Selma, the self-proclaimed raisin capital of the world.

“You wonder why people write poetry out of these small towns?” Everwine asks. “That’s how they make themselves heard. You have to do something to say, ‘Here I am.’ ”

Luis Omar Salinas, a guru of Chicano poetry nationwide, sleeps in a tiny room in Sanger. On the wall above his narrow bed hangs a hatrack and a crucifix. Over the electric typewriter is a 1993 calendar from Benny’s Toyota graced by a snapshot of Salinas, his uncle and Salinas’ new car.

Loneliness runs through Salinas’ work, like the rivers that traverse the San Joaquin on their way from the Sierra Nevada to the sea. “It’s a part of life. It’s a part of my life,” he says. “I can’t hide it.”

It doesn’t help that he lives in one of the dozen satellite farm towns on the edge of Fresno proper. It doesn’t help that he spent much of his life plagued by schizophrenia, since tamed with the help of medication, or that, fiftysomething, he lives with an aging aunt and uncle instead of a wife for whom he pines. It does help that he writes poetry.

I wish to tell someone

my heart has gone

out of doors, in its suit

of silver, ragged and pained.

And that my waltzing mind

has nowhere to go anymore.

--from “Imbecile Lament,” by Luis Omar Salinas

Salinas wrote his way through undergraduate poetry classes at Fresno State in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time, says poet Roberta Spear, when “it was the hottest place west of the Mississippi.”

Spear grew up in nearby Hanford, a town she spent her adolescence plotting to leave. She did break free of the Central Valley and studied for awhile in the 1960s at UC Irvine under Galway Kinnell, one of the brightest lights in contemporary American poetry.

When Kinnell left Irvine, Spear did too. Much to her chagrin, she ended up back here in 1969. “I said to [Kinnell], ‘Where should I go?’ ” Spear recounted. “He said, ‘Probably the best place is Fresno State.’ ”

Jazz livened downtown clubs in 1960s Fresno, literary luminaries were drawn here to read from their work, and Levine was not much older than his students.

Fresno has since grown to a population of nearly 400,000 in a rapid transformation that has replaced farmland with tract homes, serenity with car theft and arson.

The university’s writing program is in transition, too, emphasizing fiction over poetry and struggling to institute a Master of Fine Arts degree. Creative writing programs have proliferated throughout the country, lowering the Cal State Fresno program’s already low profile.

Levine and Everwine both retired recently from the university, leaving Hanzlicek as the solitary on-campus member of Fresno poetry’s old guard. Two anthologies of Fresno poetry--”Down at the Santa Fe Depot” from 1970 and the later “Piecework: 19 Fresno Poets” by a second wave of writers--have long since gone out of print.

But poet Jon Veinberg, who edited “Piecework,” hasn’t ruled out a third group work. For although many incoming students haven’t a clue anymore who Levine and Everwine are, Fresno, he insists, “is still is the place to write.”

And write they do, with varying results.

Levine, who just finished a teaching stint at Vanderbilt, returns to Fresno in June to continue work in the city “where I did my best writing.”

Poet and visual artist Dixie Salazar has a novel set in Fresno and titled “Limbo,” which should hit the bookstores this month. Janzen and Spears, who meet each month to critique each others’ work, have manuscripts in progress.

And every Thursday evening in the home economics building at Cal State Fresno, Hanzlicek meets with his graduate poetry seminar--13 women and mostly goateed men learning the hard work that poetry entails.

Here’s the drill: Each student writes a poem a week, makes enough copies for the class, hands out the poem, reads it aloud and then waits for the bad news. There is always bad news.

One poem offered up on a recent evening centered, like many Fresno conversations these days, on public crime and private response--in this instance the graffiti that despoils a fence separating yard from field behind the author’s house.

Another began with an almost elegant description of fly fishing and ended with Bigfoot. Hanzlicek found a phrase he liked, half a line out of a flowery 32.

The agonized poet had tried to amputate some adjectives, but admitted that he “fell in love with every one of them.”

“That’s what we’re here for,” said a classmate, echoing nearly 30 years of blunt advice given to writers in this down-to-earth city, “to disabuse you of that notion.”

*

I appear

dogbeaten

amid beer

and the promise

of the future.

Here I am

out of work,

disconsolate,

enamored of birds,

ready to take flight

myself.

-- Luis Omar Salinas, from “Watching it Move”

*

Hunger with its open face,

its open mouth. Simple

as a life-line. I love

the old man’s story--

the miracle in the Ukraine--

how that loaf of bread slid off

the military wagon into the snow

and saved his whole family.

Survival and escape from

the unspeakable desert.

--Jean Janzen, from “Eating Stones”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.