Laughter Turns to Tears for Comic With MS

- Share via

Once upon a time, the former Tina Plackinger lived for those moments when she would stand on stage in a two-piece bathing suit and flex her formidable muscles with all her might. In 1985 she was crowned the women’s bodybuilding champion of the world. She loved it--and she hated it.

“I’d get standing ovations. Then I’d go home and I knew I was killing myself.”

She was abusing anabolic steroids and amphetamines. She had no menstrual cycle, her voice was low, her hair was falling out and she suffered episodes of intense hostility known as “roid rage.”

The other night, her system now free of drugs, Tina, 37, stood on stage at a bingo hall in Woodland Hills. She wore a tuxedo with tails, serving as the emcee for a fund-raiser honoring the husband she met through a narcotics recovery program.

Christopher Sylbert is a comic who’s kicked heroin and methadone. Now Tina and his pals want to help him buy a new drug. It’s called Copolymer I, an experimental medication for multiple sclerosis. If Chris, 44, can muster the strength to put aside his walker and take a short hike with his cane, he might qualify for the clinical trials.

*

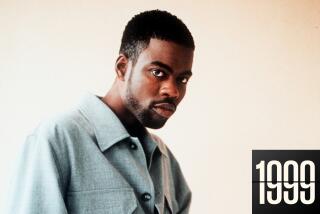

Chris sat front and center, too fatigued to perform this night, and it was a shame. I first met Chris last October, when he stole the show at the L.A. Cabaret’s annual “Funniest Person in the Valley” competition. With his tough Bowery Boy accent, he complements material that deftly plays off his frail condition. A one-liner that comes to mind concerned his fanciful career as a gigolo: “Dat broad was so big she was protected by Greenpeace.”

Chris was a Hollywood sign painter who had honed his comedic skills in rehab programs before stepping on a stage. Of more than 200 people who showed up for his benefit, most had gotten to know Chris during his visits to meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. They called him “Stick” because he walked with a cane.

Most of the guests, and all of the entertainers, were friends. The opening act was a comic named Alonzo--just Alonzo--who noted that Tina’s invitation requested “semi-formal attire.” He surveyed the room and scowled. “In N.A.,” he concluded, “semi-formal means hide the tattoos.” Later would come singer Joe Ferguson and a comic named Dante--just Dante.

Not exactly household names. But the headliner was an entertainer of international repute, the New Orleans piano man known as Dr. John, known for his 1970s hits “Right Place, Wrong Time” and “Such a Night.”

It can be odd to witness a major talent play a minor benefit in a bingo hall. Most of the people here came as friends of Chris, not as fans of Dr. John. People talked throughout his performance, but he didn’t seem to mind. To Chris and Tina he dedicated “Makin’ Whoopee” and to Chris, “My Buddy.”

Dr. John, whose real name is Mac Rebennack, described his own struggle with heroin in his autobiography “Under a Hoodoo Moon.” In 1989, he had come out to L.A. and wound up “in a psych ward.” One day, as Chris recalls it, singer David Crosby brought Rebennack to a rehab group.

“Mac heard me speak and he says, ‘Hey, kid, I’m gonna give you a call and maybe you can come out to the piddle I’m in and take me to the meeting.’ ”

A piddle ?

“That’s a hospital,” Chris explained.

So when Rebennack needed a friend, Chris was there, day after day.

*

Chris was healthier then, still using his cane. Tina was just somebody he knew through N.A. He thought Tina was attractive, but crazy. She thought Chris was a bit too happy-go-lucky for an ex-junkie with MS. “I thought he was full of you-know-what,” she says.

By the time Chris asked the ex-bodybuilding champ out, he had put the cane aside and was using a metal walker. On their first date, Tina recalls, “We fell mad, crazy, head-over-heels in love. He asked me that night if I would be his girl. And I thought, man, these N.A. guys sure are fast.”

They’ve been married two years now, and Tina knows Chris isn’t always happy-go-lucky. There is no cure for MS, only treatments that may slow the disease. Because he is unable to tolerate other medication, Chris thought he would be a good candidate for Copolymer I trials, estimated to cost $7,500 per year. But recently, his doctor explained the Copolymer I trials specify that the test patients be able to walk with a cane. Chris broke down in tears.

He’d been using the walker for short distances, the wheelchair for longer jaunts. It doesn’t seem fair. It isn’t fair. But the other day, Tina handed him one of his canes and told him to practice.

He wants to get a new cane, the kind that stands on its own four feet. Chris says he’s trying with his old stick, but it’s hard.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.