On the Waterfront : Author William Least Heat-Moon, who explored America’s back roads for his ‘Blue Highways,’ takes to the nation’s rivers--5,400 miles in all--gathering insights for a new book.

Nikawa, a word from the Osage language, means river horse. From the Missouri tribe contributing a strain of his heritage, author William Least Heat-Moon has chosen this name for the 22-foot cruiser he has piloted for four months on a river odyssey across America.

Nikawa’s gait is determined by the waters. This morning on the Columbia River near Portland, Ore., smooth waters give it a rolling lope. But as the day progresses, winds spur the gray-green waters into swells that make the river horse gallop and rear.

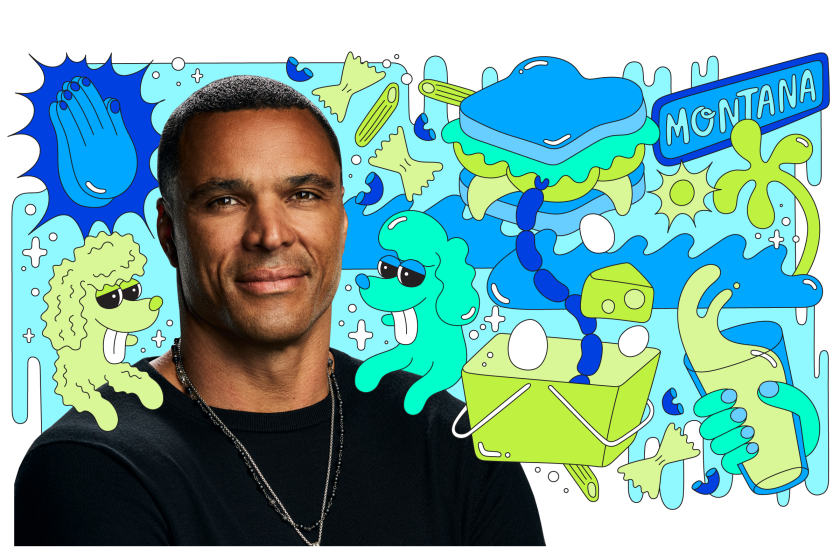

Boat and captain have traced some 5,400 miles of waterways since the trip’s beginning in New York City. On an earlier odyssey, Heat-Moon cruised 13,000 miles of U.S. back roads in a Ford van called Ghost Dancing. The result was his 1983 bestseller “Blue Highways,” in which the Columbia, Mo., author explored America’s soul as well as his own. Now, gathering adventures for a new book, Heat-Moon makes his way on what some call the nation’s oldest blue highways--its rivers.

His route has taken him from the Hudson River to the Erie Canal to Lake Erie, with portages at the top of Lake Erie and Lake Chautauqua. Then on to the Allegheny, Ohio and Mississippi to the Missouri, which took up about half of his journey. From there, a portage over the Continental Divide to the Lemhi River, then on to the Salmon, where an outfitter took him over white water by raft, then the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific.

In Nikawa’s compact cabin, Heat-Moon, 55, controls the helm under a wooden sign with the Quaker saying, “Proceed as the Way Opens,” one of two messages that guide this journey. Above the cabin door hangs the second, from Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”: “Avoid Irritation.”

“If I follow those two things, everything’s all right,” he says.

Tanned hands knowingly gripping the wheel, the captain keeps an alert posture even though the pace sometimes bounces him above his seat. His face, ruddy from wind and sun, contrasts with his silvery beard and hair, which he remarks grows whiter with every trip. Lively blue eyes constantly scan the river horizon.

Just shy of reaching the Pacific, a man whose previous boating experience had been limited to the two extremes of paddling a canoe and working aboard a 900-foot aircraft carrier during a two-year Navy hitch, ponders the power of the river and its influence on time.

“It’s the shortest four months I’ve spent in my life,” he says. “The river sort of eats our conception of time. The time that counts on the river is the flow of the river itself . . . and light and dark.”

*

In what light exists before 6 a.m., Heat-Moon rises to check the winds and determines an early run is needed for a smooth ride to the next stop, Cathlamet. The clouds will keep the winds down.

During his time on the Columbia, Heat-Moon receives navigational help from friend Steven Ratiner, a Massachusetts poet and teacher who was among several writer or aspiring-writer friends who served as co-pilots and crew on different legs of the trip. More than one set of eyes are needed to read the navigational charts. Heat-Moon is a stringent captain, sometimes reeling Ratiner in from talk other than what might be read from the “River Cruising Atlas,” detailing depth and markers along the river.

Heat-Moon keeps his own writing eyes open, stopping to take photographs and noting both the ominous presence of an old nuclear cooling tower and the graceful skill of a cormorant plucking a small salmon from the water.

The voyage is showing him the country anew, and Heat-Moon hopes to relay that perspective in his forthcoming book.

“I really want it to be a book about the way we are--as a people and as a land--expressed by the life and topography along our great rivers,” he says.

With the river keeping time, he swam in the Erie Canal, battled merciless winds on Lake Erie, coursed through floodwaters on the Mississippi and Missouri, and rode the rapids of the Salmon by raft. He and crew camped a bit, but also spent nights in river towns and villages to capture the flavor of life along the waterways.

His research is historical, cultural and, particularly, environmental, as much of his route has followed rivers listed as endangered by American Rivers, a Washington, D.C.-based conservation group. The waterways have been polluted by farming and cities, straitjacketed by flood-control projects, and dammed to the point of eliminating a number of species of salmon, says Rebecca Wodder, president of American Rivers. She hopes Heat-Moon’s voyage and book will bring attention to rivers, which have “fallen into a national blind spot.”

While much of the country originally moved via the rivers, “One of the sad things I’ve seen is that so many of these places have forgotten that,” Heat-Moon says of cities that have literally turned their backs on the waterways. Some towns where Heat-Moon wanted to stop offered no docking or access from the river.

But the journey left him optimistic, inspired by the still-pristine beauty of America from this angle, and the hospitality of people along the way, including a man on the Mississippi who let Heat-Moon tie up Nikawa in his front yard during rising floodwaters and then fed him a catfish dinner.

*

Heat-Moon had long thought his next book would be a celebration of water. In January, 1994, he narrowed the focus to the river voyage, aiming to make the trip in one season with as few portages as possible.

“I made the trip many times on my desk with my finger,” he says, and he scouted the route by land.

This trip would be on a stricter itinerary than past journeys, since Heat-Moon had to catch the peak of the Missouri’s flow, and meet an unchangeable date with an outfitter for the raft trek on the Salmon.

Two months before his sailing date, he still hadn’t found the right boat. Then he spotted the flat-bottomed, fiberglass C-Dory in a boating magazine and purchased it from the Seattle manufacturer at cost--$15,000. Two Honda 40-horsepower engines, both environmentally advanced and fuel efficient, cost $10,000. Other equipment, such as a kayak, canoe and radios, he borrowed.

“It’s not a sexy little boat,” he says, but “highly maneuverable and extremely responsive.”

Particularly challenging was Lake Erie, where winds whipped up swells of seven feet that tossed Nikawa and crew for six hours.

“It was the longest I’d ever been scared in my life,” he says. “After we came off of that and we tied up, we looked down at this little boat at the dock. It looked so tiny. I wanted to go down there and put my arms around that boat and say, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you.’ And I had a sense it cared we’d made it.”

Nikawa and Heat-Moon were tested again during flooding in the Midwest, particularly on the Missouri, where drifting trees with huge trunks torpedoed the boat. He marveled at the tenacity of people who battled the flood, and he helped residents of New Haven, Mo., with sandbagging.

But the Missouri in flood offered a fascinating beauty as well, the water high into the trees. From it, Heat-Moon also saw a new view of Kansas City.

“I grew up in that city and have seen it from every possible angle except that one. The buildings line up just right there to make a great view of the skyline.”

William Trogdon was born in Kansas City in 1939. He owes his pen name to his father, a Scoutmaster who called himself Chief Heat Moon and nicknamed his oldest son Little Heat Moon and youngest (William) Least Heat Moon. Trogdon became Least Heat-Moon the author with “Blue Highways” (Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1983).

In “PrairyErth” (Houghton Mifflin, 1991), Heat-Moon’s literary periphery was tighter, but no less deep. He walked the plains through tallgrass, plunging into the lives, history and terrain of Chase County, Kan. The resulting work was meant to inspire others to reconnect with their own lands.

The boots Heat-Moon wore when he hiked the Kaw Trail for “PrairyErth” are now on display in the Chase County Historical Society Museum, symbols of a time when he went “in quest of the land and what informs it.” Wearing the shoes of a boating man--Sperry Top-Sider deck shoes--he speaks of drawing similar knowledge from the rivers.

“This book will be particularly hard because I don’t want to repeat what I’ve done before, but still keep it in the spirit and somewhat akin to the other two books because I do conceive it now as three facets of really one journey.”

*

Half of the route paralleled the journey of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who explored from the Missouri to the mouth of the Columbia in the early 1800s. A lesser-known pair, German explorer Prince Maximilian zu Wied and Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, traveled from the East Coast to Montana and back by steamboat in the 1830s, recording in words and paintings life in the West at that time. “It’s a loss as a nation not to know some of this,” Heat-Moon says of the duo’s work.

River travel today, he says, is like seeing the country much as these early travelers did. He saw only four billboards the whole way and saw very little evidence of urban sprawl.

“With a few exceptions you come away with the notion that is an incredibly beautiful country that has slightly been touched by the hand of humankind.”

Still, the rivers have been touched, and Heat-Moon says 75% of his reason for taking the trip stemmed from environmental concerns about them. Swimming in and drinking from the waterways showed him positive signs that American rivers are far less polluted than two decades ago.

“There was one place on the Ohio River in Indiana that was almost paved with plastic. But the rest of the way, you don’t see much litter.

“I’m very concerned now about Congress fouling up the Clean Water Act, which has done so much to clean up our rivers,” he says. “Twenty years worth of work shows on our rivers.”

On Aug. 1 in Cathlamet, Wash., Heat-Moon says he needs time to prepare for the next day’s finish at the Pacific--right on schedule despite four months at nature’s whim.

“It’s something that’s been very big in my life for the last year and a half, which is not going to be there anymore,” he says.

Just before 7 a.m. the next day, he steers Nikawa under placid gray skies down a quiet river back road to avoid rough waters. In about an hour, a distinguished landmark is spotted.

“By God, is that the damn bridge I see there?” Heat-Moon says happily and peers through binoculars at the lengthy Astoria Bridge. Nearing Astoria, he reaches through the window to collect water on his fingers for a taste. “It’s not salty yet--I’m kind of surprised.”

He then offers an “immortal quotation” from the journal of William Clark: “O, joy. Ocian in view,” referring to the explorers’ premature perception they had reached the ocean at Astoria.

Landing at the Astoria Mooring Basin marina, Heat-Moon steps from the boat to express his own joy and dances a jig on the dock, giggling gleefully. But crossing the notorious Columbia River bar into the Pacific still remains.

This final test is described in William Dietrich’s “Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River” as “the third most dangerous river entrance on Earth. . . . Approximately 2,000 vessels, more than 100 of them major ships, have sunk here. An estimated 700 people have drowned.”

Heat-Moon dons a life jacket for the first time on Nikawa. “Our moment has arrived,” he says.

The Coast Guard vessel Bay Mist leads Nikawa out to sea. Although Ralph Gilbert of the Coast Guard Auxiliary says the surf today is “as flat as it gets,” the gray waters of the Pacific toss the boat like a toy on swells of up to 10 feet, yet far enough apart to allow Nikawa to ascend and descend as if on a slow-moving roller coaster. The river horse soars like Pegasus.

Heat-Moon and crew see the perils of the bar when another Coast Guard boat must rescue a stranded craft that has lost power.

At 11:23 a.m., Gilbert gives the official announcement on the radio: “Nikawa, this is the Pacific.”

Heat-Moon slows the boat and hands the wheel to Ratiner. From a cupboard, he removes a Snapple bottle partly full of water collected from the Atlantic Ocean at the beginning of his voyage. Balancing himself against the heaving of the small boat, Heat-Moon stumbles from cabin to stern, where he holds the bottle high and lets the water from one ocean mix with another, following a similar gesture by De Witt Clinton, who carried a barrel of water from Buffalo along the Erie Canal to New York Harbor and poured it in.

Then Heat-Moon raises his arms to the sky in “an Indian thanks for a safe journey directed to the spirits of the rivers.”

Later, while waiting for a trailer to pull Nikawa from the water, Heat-Moon privately makes another offering from one ocean to another. Along the way he has carried in his pocket small stones from several of the rivers. Now he leaves a small round gray stone from the East Coast on the Columbia River’s bank at Astoria.

“I thought about tossing it out in the ocean,” he says, “and then I thought about how hard and how long that little rock had worked to get where it was going.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

The Original Blue Highways

Author William Least Heat-Moon, who crisscrossed America in a Ford van to research his 1983 bestseller “Blue Highways,” recently piloted his 22-foot boat from New York to Portland Ore., along a series of rivers. The 5,400-mile voyage took four months.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.