A Trip Down ‘Soul Train’s’ Memory Lane : Commentary: With a 25th anniversary special airing tonight, an observer points out how the show stood at the forefront of what was to become the watershed moment in African American popular culture.

The train has been a recurring icon in African American history. From the underground railroad to the prestigious era of the Pullman porter, the train and its relevance to black history are undeniable.

Even in popular culture, the abiding symbolism of the train has often been used as a vehicle that could transport one from an oppressive state of mind to a liberated space of emotional bliss, as evidenced by songs such as the Impressions’ “People Get Ready (There’s a Train a Coming),” the O’Jays’ “Love Train” and Gladys Knight’s “Midnight Train to Georgia.”

Yet for all the history and culture embedded in this image, no train has been quite as underestimated or quite as funky as the one that has rolled across our television set for the last 25 years in the form of that familiar whistle on “Soul Train.”

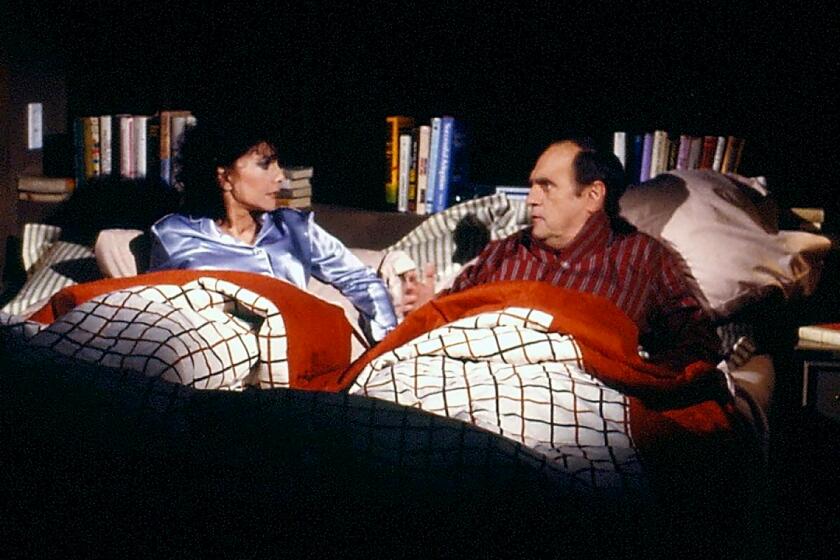

In its prime, the program, which celebrates its quarter-century anniversary with a two-hour special on CBS tonight, featured celebrity musical guests and of course highlighted its magnanimous host and creator, Don Cornelius, but the true stars of “Soul Train” were the dancers. These dancers were “real” black people, representing the common man and woman--doing the latest dances, wearing the hippest clothes and sporting those fly hairdos.

“Soul Train” was black style personified. “Soul Train” offered blackness in its funkified essence. As the show’s tag line suggested, it was “the hippest trip in America.”

The program’s importance, though, reaches much further than simply being another dance show. Arriving in 1970, “Soul Train” stood at the forefront of what was to become the watershed moment in African American popular culture. With the blaxploitation movement beginning to take hold in Hollywood, along with the increasing presence of blacks on television--from Flip Wilson to Fat Albert--”Soul Train” was the connection between fictional African American characters and everyday people.

Even though “Shaft,” “Super-fly” and “Cleopatra Jones” were seductive images that empowered like never before, the majority of the films from this era were studio-controlled images that used a black cast and black narratives, but seldom used blacks in any creative or financially beneficial capacity. Blacks were relegated, as always, to performing.

While the movies of the blaxploitation era were a welcome relief from previous images of characters scratching where they did not itch and laughing when things were not funny, the films were an exaggerated saccharine fantasy, providing a momentary sugar rush of cultural satisfaction but devoid of lasting creative or financial nourishment. Likewise, most of television’s popular situation comedies of the day were satisfactory for a time but now look like recycled images of Buckwheat and Stepin Fetchit, simply nuanced for a different era.

“Soul Train” offered an alternative. The program put the political dictates of black nationalism into action through popular culture. Finally, African Americans in the mass media were controlling their own image--and their own money to boot.

Taking its lead from the financial ascendancy of record companies like Motown, Stax and Philadelphia International, “Soul Train” combined the music--something that blacks had long held sway over--with the visual medium of television, assuring that black music and culture would not only be heard but also seen.

For all its faults, television can provide a certain legitimacy, a form of cultural identity for those who see their image represented in an affirmative way. And in a society that had fully adopted the television set as a vital component in the domestic sphere, “Soul Train” assured a black presence when all other forms of representation were leaving something to be desired.

Yet like all good things, the significance of “Soul Train” would eventually run its course. By the mid-1980s, music videos began to replace the need for live performance shows like “Soul Train.”

As a matter of fact, one of the real downfalls of “Soul Train” was its inability to respond to change. Like an oversized, gas-guzzling Cadillac, “Soul Train” had become obsolete, a relic, a marker of a bygone era. “Soul Train’s” once rapid trajectory had slowed to a snail’s pace. What remained of the program’s earlier contribution had been gobbled up by MTV, with BET taking the leftovers. When Cornelius stopped hosting the show in 1993, in favor of questionable “celebrity guest hosts,” the program was about as relevant as an eight-track stereo in a world of compact disc players.

American culture has recently rekindled interest in the 1970s. In this regard, “Soul Train” has started to receive its well-deserved props. As indicated by Spike Lee’s “Crooklyn” and the Hughes brothers’ “Dead Presidents”--both of which feature key scenes that revolve around watching “Soul Train”--and the prime-time airing of the 25th anniversary special, among other things, the program has finally been redeemed and rewarded by history.

* “The Soul Train 25th Anniversary Hall of Fame Special” airs at 9 tonight on CBS (Channel 2). “Soul Train” airs Saturdays at 1 p.m. on KTLA-TV Channel 5.

Todd Boyd is a professor of critical studies at the USC School of Cinema-Television.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.